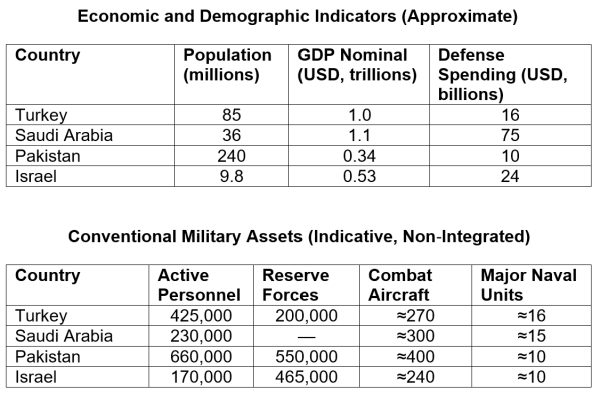

Recent reports of preliminary negotiations for a military alliance of Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan raise underappreciated risks. Similar concerns arise from Israel’s growing security cooperation with the United Arab Emirates and its reported engagement with Somaliland, developments that have sharpened regional rivalries and prompted countervailing alignment efforts by Somalia involving Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Concerns about emerging Middle Eastern alliance formations are often dismissed with a familiar argument: regional states have a long history of failed collaboration. Past alliances were informal, fragile, and undermined by rivalries. From this perspective, new Mideast defense pacts and collective security declarations are more symbolic than consequential. They are therefore assumed not to merit serious concern.

This reasoning gets the risk almost exactly backwards. It is not the strength or cohesion of these alliances that makes them dangerous. It is their weakness. Weak alliances generate ambiguity without control. They signal shared purpose without establishing clear command authority, escalation thresholds, or mechanisms for restraint. They encourage participants to act as though backing exists while leaving open the question of who, if anyone, can prevent overreach once events unfold. In a region already saturated with unresolved conflicts, this combination is inherently destabilizing.

2025 Saudi Pakistan mutual defense treaty – More security or greater danger?

Why Weak Alliances Increase Escalation Risk

Strong alliances can deter or manage conflict by clarifying commitments and enforcing discipline. Weak or informal alliances do the opposite. They increase conflict risk in several ways.

First, fragile alliances multiply interpretations without consolidating authority. Each participant, and each rival observer, must infer what commitments actually exist. Actions that one actor views as symbolic reassurance may be read by others as tests of resolve or credibility. The absence of clear escalation rules means that signaling takes the place of strategy.

Second, weak alliances lower the barrier to adventurism. States may undertake risky actions believing that partners will be drawn in by reputational pressure even if no formal obligation exists. Alliance signaling substitutes for coordination, encouraging behavior that would otherwise be constrained by fear of isolation.

Third, and most dangerously, weak alliances prolong conflict without resolving it. Because no alliance member possesses the authority to compel restraint or decisive action, conflicts are more likely to remain indecisive. It is precisely this condition that historically invites outside intervention.

The Thucydidean Pattern: Weak Coalitions and External Intervention

The classic illustration comes from the Peloponnesian War. Athens ultimately fell not because the Spartan alliance possessed overwhelming internal cohesion, but because the long conflict created the conditions for Persian intervention. Persia did not intervene out of ideological alignment or moral preference. It intervened opportunistically—funding Sparta when it became clear that Athenian dominance could be checked but not decisively overturned by Greek powers alone.

This pattern recurs throughout history. External powers enter conflicts not when one side is clearly dominant, but when prolonged struggle makes the outcome uncertain yet strategically consequential. The intervention is not driven by alliance loyalty, but by opportunity. Later examples follow the same logic. France entered the American Revolution only after Saratoga demonstrated that Britain could be challenged but not quickly defeated. Britain seriously contemplated intervention in the U.S. Civil War only when the conflict appeared prolonged and indecisive. In each case, the decisive actor was not a primary belligerent at the outset, but an external power drawn in by a strategic opportunity.

The lesson is clear: weak or fragmented alliances do not dampen conflict; they extend it, increasing the likelihood that outside powers will intervene to shape the outcome. Applied to the Middle East, this logic is deeply concerning. Loose regional coalitions are unlikely to achieve rapid resolution. Instead, they risk creating extended, ambiguous conflicts that invite escalatory intervention by external powers—whether the United States, the European Union, Russia, or China—each with its own strategic calculus. In the nuclear era, such interventions carry enormous risks.

Escalation Triggers

This dynamic becomes especially dangerous because escalation does not require extraordinary events. It arises from routine military and security incidents that, under clearer authority structures, might be manageable. Aircraft shoot-downs, ship seizures, declarations of no-fly zones, and maritime blockades are not novel. They occur regularly in contested regions. Under weak alliance conditions, however, these incidents are rapidly reframed as alliance tests rather than isolated disputes. An aircraft shoot-down becomes a credibility challenge. A ship seizure becomes a test of collective resolve. A no-fly zone declared without unified enforcement becomes an invitation to probe. A blockade, formal or de facto, turns into a regional contest over prestige and access rather than a bounded coercive tool. Because alliance commitments are ambiguous, responses are improvised. Symbolic gestures harden into military deployments. Signaling intended to deter instead provokes counter-signaling. Escalation proceeds not because anyone plans it, but because no one clearly controls it.

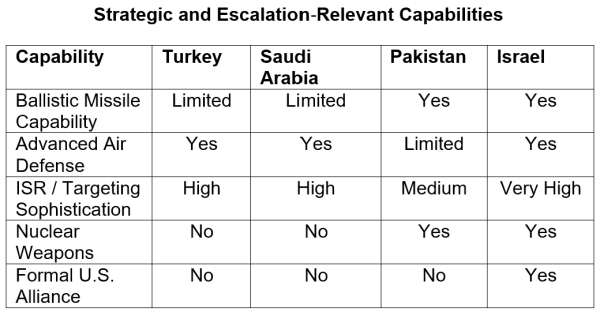

Nuclear Compounding Without Nuclear Intent

These risks are fundamentally altered when nuclear-armed states are involved, even indirectly. Nuclear weapons need not be deployed—or even seriously contemplated—to shape crisis behavior. The presence of nuclear-capable actors raises the perceived stakes of miscalculation, compresses decision timelines, and intensifies fear of abandonment or encirclement. States may feel pressure to escalate signaling early to avoid appearing weak, narrowing off-ramps before they are fully visible. Nuclear capability becomes a psychological anchor in crisis perception rather than a last-resort option. This is especially destabilizing when nuclear-armed participants are embedded in weak alliance structures that generate expectations without guarantees. Ambiguity becomes intolerable precisely because the perceived costs of misreading it are so high.

Volatility as a Regional Risk Multiplier

All of these structural risks are magnified by the historic volatility of Middle Eastern state security perceptions. Several states in the region operate under doctrines—explicit or implicit—that treat even limited military challenges as potentially existential. This orientation is not irrational. Many regional states were formed through war, territorial contestation, or abrupt political rupture. Borders, regimes, and governing institutions have repeatedly faced collapse, external intervention, or both. As a result, decision-makers often interpret military incidents not as negotiable disputes, but as possible preludes to regime-threatening escalation. In such an environment, alliance ambiguity does not reassure. It intensifies fear. Weak alliances increase anxiety about abandonment while simultaneously encouraging risky demonstrations of resolve. A limited incident can rapidly be reframed as a struggle over survival rather than a problem to be contained.

The Escalation Trap

The central danger, then, is not any particular alliance, nor the prospect that regional states will suddenly discover unprecedented military cohesion. It is the multiplication of escalation risks in a region predisposed toward worst-case interpretation. As overlapping, informal, and evolving Mideast alliances proliferate, escalation risk grows non-linearly. Each new security tie adds interpretive pathways, perceived obligations, and opportunities for opportunistic intervention. No single actor controls the escalation logic. Even limited conflicts acquire disproportionate strategic meaning.

Conclusion

Emerging Middle Eastern alliances should not be dismissed because they are weak. They should be taken seriously precisely because their fragility amplifies ambiguity, encourages risk-taking, and magnifies the consequences of miscalculation, especially in a region where existential threat perceptions and nuclear capabilities are prominent concerns. In such conditions, alliance formation does not necessarily enhance security; it can instead multiply the possibilities for local crises to escalate into wider conflict. For external powers, the danger lies not only in what these alliances intend, but in how they interact with already volatile regional politics. Without sustained efforts to reduce tensions and clarify escalation boundaries, the search for security through new Mideast alliances may ultimately backfire, increasing rather than containing the risk of a strategic catastrophe.