Until very recently, nuclear proliferation was treated primarily as a problem of rogue states, revisionist regimes, or localized regional instability. The prevailing assumption was that restraint would be rewarded with security guarantees, legal protection, and predictable international behavior. That assumption is no longer tenable. The systematic breaching of legal and institutional limits on the use of force by the United States has begun to reshape global security incentives. As U.S. aggression becomes normalized, legally unmoored, and increasingly detached from diplomatic norms, nuclear weapons reassert themselves as the only credible deterrent against coercion by superior military powers.

The Signal Being Sent

Recent U.S. international conduct communicates a stark and globally legible message: international law is optional, treaties are contingent, and security guarantees are political rather than institutional. Covert action, paramilitary force, and the threat of unilateral military intervention have become routine tools of policy rather than exceptional measures. When senior U.S. officials openly assert unchallenged authority to attack other nations and seize their resources, the lesson absorbed abroad is unmistakable. State sovereignty cannot be protected by rules or norms that powerful actors openly disregard. For nations with sufficient resources and technical capacity, this logic points directly toward recourse to nuclear deterrence.

Why Nuclear Weapons Reassert Their Logic

Nuclear weapons have always functioned primarily as tools of regime survival rather than instruments of battlefield utility. As treaty compliance fails to deliver protection and diplomatic alignment fails to guarantee restraint, deterrence regains primacy. A nuclear weapons capability offers a uniquely efficient means of deterring both superpowers and regional adversaries. Even a small number of deliverable, rudimentary nuclear weapons sharply increases the risks faced by any potential attacker, altering strategic calculations in ways that no attainable conventional force can replicate. Proliferation pressure today reflects defensive rationality under weakened international norms, not ideological ambition or militaristic fervor.

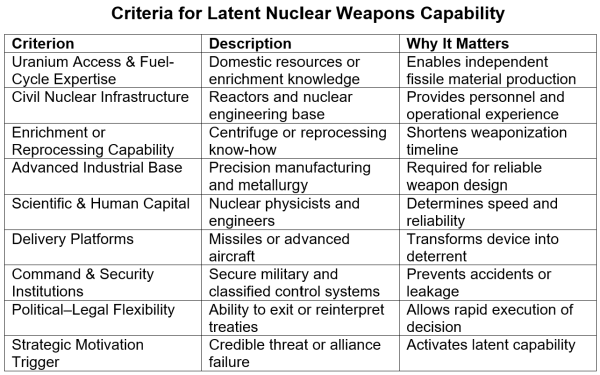

What Latent Nuclear Capability Means

Many states already possess latent nuclear capability: the ability to cross the nuclear threshold rapidly once political authorization is given. Latency reflects possession of the human capital, financial resources, industrial base, and technical expertise required to develop and produce nuclear weapons. In such cases, the principal constraint is not practical feasibility but political restraint. As confidence in international norms erodes, that restraint weakens, compressing timelines from decades to years, and in some cases to months under crisis conditions.

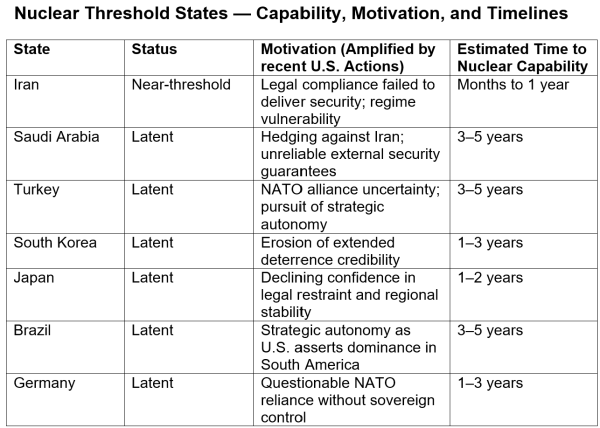

Threshold State Assessments

Iran

Iran demonstrates with particular clarity how legal compliance can fail to deliver security. After years of restraint, intrusive inspections, and formal adherence to international agreements, compliance neither prevented sanctions escalation nor shielded Iran from covert sabotage, cyber operations, or persistent military threats. From Tehran’s perspective, compliance arguably increased vulnerability by exposing constraints without delivering reciprocal restraint. With Iran already near the technical threshold, the remaining barrier to weaponization is political rather than technical. As confidence in reciprocity collapses, nuclear capability increasingly appears not as leverage for negotiation, but as a necessary guarantor of regime survival.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s nuclear calculus reflects strategic hedging rather than ideological aspiration. The Kingdom has explicitly linked its nuclear posture to Iran’s trajectory while confronting the limits of externally provided security guarantees that are visibly transactional and reversible. Recent experience has underscored that alignment does not ensure automatic protection or enduring commitment. In a system where alliance assurances appear contingent and legal constraints on force weaken, sovereign nuclear deterrence emerges as an insurance policy against abandonment rather than a bid for regional dominance. Saudi Arabia has long been suspected of pursuing a form of nuclear threshold capability through its relationship with Pakistan: financing nuclear development in the past and maintaining a contingent deterrence understanding that could be activated in extremis. While there is no public evidence that Riyadh possesses nuclear weapons or completed designs, the existence of such arrangements underscores how states adapt to weakened nonproliferation norms without crossing formal thresholds.

Turkey

Turkey occupies an increasingly unstable position as a NATO member that hosts nuclear weapons without sovereign control while pursuing greater strategic autonomy. Ankara has openly questioned the equity of the existing nuclear order and has invested heavily in advanced industrial, aerospace, and missile capabilities. As alliance cohesion weakens and the selective application of international law becomes more apparent, Turkey’s incentive to secure independent deterrent leverage grows. This pressure arises not from expansionist ambition, but from uncertainty about whether alliance-based protection will remain reliable during acute crises. Turkey also faces the dual potential threat of nuclear-armed powers, Russia and Israel, to its north and south.

South Korea

South Korea represents one of the most compressed proliferation timelines in the international system. Facing a nuclear-armed adversary and possessing advanced industrial and scientific capacity, Seoul has long relied on extended deterrence to justify restraint. However, extended deterrence depends on predictable political commitment by the U.S. As those commitments appear increasingly volatile and subject to domestic political fluctuation, nuclear latency functions as a rational insurance mechanism against strategic abandonment. South Korea faces a far weaker northern adversary that has nevertheless succeeded in defying the U.S. by means of its nuclear arsenal. The lesson for South Korea is plain: the U.S. respects only military power.

Japan

Japan is among the most consequential restraint cases in global politics. With extensive civilian nuclear infrastructure, advanced fuel-cycle capabilities, and exceptional technological sophistication, Japan’s non-nuclear status rests almost entirely on trust—trust in legal norms, alliance predictability, and escalation control. As those assumptions weaken under regional militarization and declining confidence in rule-based restraint, the logic of permanent abstention becomes increasingly strained. Any Japanese reconsideration of nuclear posture would signal a profound failure of the postwar Asian security architecture. Japan’s neighbors have long memories of the damage inflicted by imperial Japan, and a nuclear-armed Japan would put regional relations into a dangerous state of turmoil.

Brazil

Brazil highlights the fragility of norm-based restraint under conditions of asymmetric enforcement. Long committed to multilateralism and non-proliferation, Brazil nevertheless maintains nuclear fuel-cycle expertise and a sophisticated industrial base enabling nuclear energy and naval nuclear propulsion programs. When international law appears selectively binding and force increasingly overrides restraint, unilateral compliance begins to resemble strategic exposure rather than principled leadership. Brazil’s case underscores that proliferation pressure now extends even to historically norm-oriented states once reciprocity is perceived to have collapsed. Bellicose U.S. actions in Latin America will further intensify this pressure.

Germany

Germany is the most revealing threshold case. Its postwar security identity is grounded in legalism, alliance integration, and deliberate restraint, yet it possesses the industrial, scientific, and institutional capacity to proliferate rapidly if political constraints shift. Dependence on nuclear sharing without sovereign control, combined with fears of strategic abandonment and the normalization of force outside legal frameworks, all undermine nuclear restraint. Any German movement toward nuclear capability would mark not a return to militarism, but a collapse of confidence in the system designed to prevent it. This would be a particularly alarming development for Germany’s neighbors.

From Proliferation to Entanglement: The World War I Parallel

The most dangerous consequence of renewed proliferation is not simply an increase in the number of nuclear weapons, but the alliance entanglements they generate. Each new nuclear state may extend deterrence umbrellas over allies, proxies, and aligned regimes, multiplying escalation pathways and delegating nuclear risk downward. The structural parallel to the pre-World War I alliance system is striking. Before 1914, dense and overlapping commitments transformed localized crises into system-wide catastrophe—not because leaders sought war, but because treaty obligations replaced judgment. Today, nuclear entanglement recreates this dynamic under vastly more lethal conditions, compressing irreversible decision-making into hours rather than weeks.

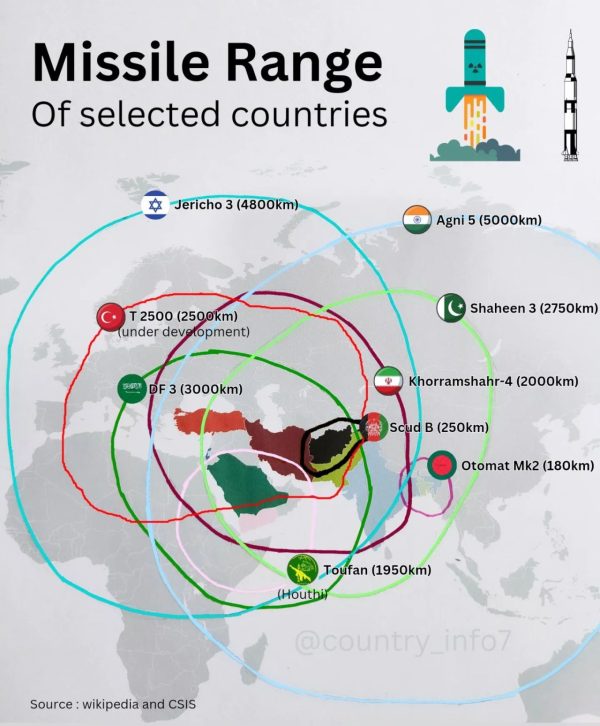

A Nuclear-Armed Middle East

To see where current incentives lead, imagine a Middle East in which Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia are all nuclear-armed, confronting a nuclear-armed Israel. This is not speculative fantasy but a direct extrapolation from existing capabilities, declared intentions, and eroding confidence in restraint. In such an environment, deterrence would no longer operate through a small number of stable rivalries, but through overlapping alliances, proxy conflicts, and credibility contests. A crisis in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, the Gulf, or the Eastern Mediterranean would no longer be readily containable. Each would carry latent nuclear escalation potential, leaving the region perpetually one misjudgment away from catastrophe.

Conclusion

The danger now confronting the international system is not abstract. It is the foreseeable consequence of a world taught that law yields to force and security depends on military capacity. When international law is treated as optional and military power as the final arbiter of disputes, nuclear proliferation becomes a rational response. As new nuclear states entangle regional conflicts with existential stakes, escalation risks may become unmanageable. A might-makes-right order does not produce stability; it creates the conditions for regional and global nuclear catastrophe. By its rash exertion of military force, the United States has sown the wind, and the world may reap the nuclear whirlwind.

I have never seen in the media, when the idea of Germany, or Japan, or S Korea to go for nukes is presented any protest that that would be against NPT andshould be banned and sanctioned by US if it happens.

Thanks Haig. Scary world we live in. Seems to be run by idiots.

Thanks, Haig. A couple of obvious points occur to me.

One is the effect of the Ukraine war. Pundits and politicians will be saying “If Ukraine had had nuclear weapons, Putin would not have invaded,” which may well be true. The pressure on Poland, for example, to go nuclear could be irresistible, especially when the US is clearly not interested in Europe any more. Whilst I don’t think they have access to most of the technologies, they have good links to the South Koreans, who do. A lot of nations (Germany?) might anyway not be happy with the Anglo-French nuclear duopoly in Europe, especially as NATO starts to fall apart.

The other is that scenarios are very different. Iran could not use nuclear weapons against Israel, for example, without killing large numbers of Muslims in the country and nearby. But it’s long been argued that the best use of Iranian nuclear weapons would be tactical: a single low-yield warhead would inflict casualties that no invading force could contemplate. More interestingly, detonating a single warhead above an invading fleet would fry the electronics (since EMP hardening is now no longer routinely done) and probably cause aircraft to fall out of the sky. Thus, we see the possibility of the return to the use of nuclear weapons on the battlefield, and the evolution of a new kind of deterrence.

To your list above, I would add guidance systems, since the blast effect of nuclear weapons falls off rapidly with distance. This is a very different issue from nuclear proliferation per se, and requires among the things the development of electronics that can withstand enormous velocities and temperatures.

If Iran had nukes it may not use them to attack Israel with, though Israel would have no problem nuking Iran. But Iran could set off a nuke over Israel to fry their electronics and send them back to the 40s. For Iran there is the problem, in a war of fighting Israel, of causing painful and crippling damage to that country but not to the point where the Israelis feel that they have to go for their nukes. That is why the Iranians restricted themselves to military and strategic targets while the Israelis would hit such targets as apartment buildings and highways full of civilian cars.

Are we ruling out straight up “transfers”of nukes instead of development? Like Brazil borrowing a little sugar from Russia if need be? Does anyone else think we could end up with more missile crises?! I truly do … Kennedy used a naval blockade to prevent missiles getting to Cuba. We are in the era of stealth bombers now. What’s to stop Colombia from getting nukes from China or Russia? Can a RS24 Yars mobile launcher (via united24media.com) fit on an AN-124 (via antonov.com)?

… asking for a friend from the Orinoco.

It’s difficult to imagine the United States tolerating nuclear proliferation. Regardless of whether nuclear weapons are developed by friendly or hostile nations, the U.S. will likely intervene beforehand.

How would the US stop it without starting a war it cannot win without deploying nukes to settle it?

Did they stop Iran? No.

Hasn’t might makes right always been the basis for any degree of “international law” or “order”? The only thing that has really changed is that the US is now saying the quiet part out loud without any degree of pretense.

The problem has always been that states can make any degree of proclamations or laws that they like on the international level, but unless they have the requisite degree of brute force to back up their degree of soft power, any claim that a state has on authority is meaningless if their opposition can simply ignore it with impunity due to the relative military superiority of stronger states.

As much as I wish otherwise, the realists seem to be right when it comes to why we always seem to be locked in endless cycles of international conflict.

Ignorance is due to censorship, but clues abound.

Heavy isotopes are no longer needed for fusion devices.

Tritium and antimatter suffice. Neutron device. View the detonation, especially the velocity of the force in Beirut years ago.

Mr. Mearsheimer making the argument for an Iranian nuke in 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6hjfBGI7qXg

The Germans already have control of several US nuclear gravity bombs and the capacity to use them.

But the thought of that pestilential country developing an independent nuke is terrifying. The victors of WW2 should act quickly to disarm and re-partition Germany!

(Not Sarc)

Why does the USA think it has a right to have nuclear weapons but other countries do not