Yves here. Germany seems determined to test the Eurozone experiment to destruction. As we’ve long said, it insists on contradictory aims: running large trade surpluses, not being willing to finance them, and not permitting high levels of fiscal spending to serve as another mechanism to provide for transfers to “deficit” countries. By contrast, people in New York and California don’t even think much about the fact that they are getting less out of the Federal government than they pay in taxes and are effectively supporting consumption in places like Mississippi.

By Wouter den Haan, Professor of Economics and Co-Director of the Centre for Macroeconomics, London School of Economics; Martin Ellison, Professor of Economics at the University of Oxford; Ethan Ilzetzki, Assistant Professor, London School of Economics; Michael McMahon, Associate Professor of the Department of Economics, University of Warwick; and Ricardo Reis, A.W. Phillips Professor of Economics, LSE. Originally published at VoxEU

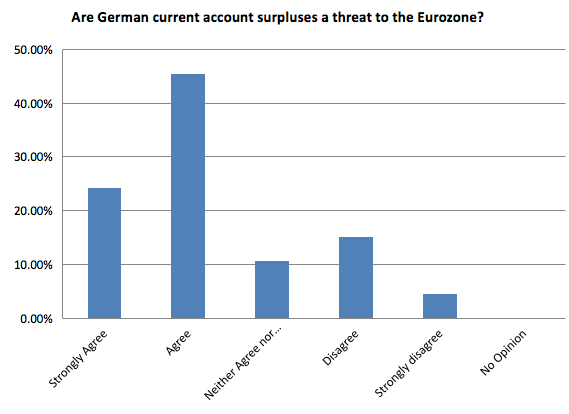

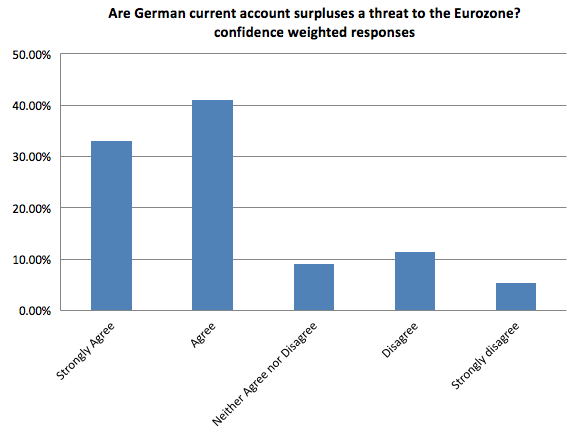

The October 2016 expert survey of the Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM) and CEPR invited views from a panel of macroeconomists based across Europe on Germany’s trade surplus, its impact on the Eurozone economy, and the appropriate response of German fiscal policy. More than two-thirds of the respondents agree with the proposition that German current account surpluses are a threat to the Eurozone economy. A slightly smaller majority believe that the German government ought to increase public investment in response to the surpluses.

Germany posted a record-high current account surplus of 8.5% of GDP in 2015; indeed, the German surplus has overtaken China’s surplus as the largest in the world. Germany’s current account was slightly in deficit when the euro was created in the late 1990s, it steadily increased in the early 2000s and has continued to rise since the Global Crisis of 2008. Since 2010, the increase in the current account has been accompanied by fiscal surpluses, with the German government moving from a deficit of 4% of GDP in 2010 to a surplus of 1.2% in the first half of 2016.

Global Imbalances

Through the prism of the trade balance, the current account surplus can be viewed as a symptom of Germany’s economic success. German exports increased from 30% of GDP in 2000 to 47% in 2015. But with imports at merely 39% of GDP, this implies that Germany is providing capital to the rest of the world at a very high rate. Indeed, German savings have increased from roughly 20% to nearly 30% of GDP, while domestic investment has remained roughly constant at around 20% of GDP.

One view, harking back to Keynes, is that such large capital flows could be very destabilising, particularly within a system of fixed exchange rates (or a currency union). The argument is that while countries with current account deficits may come under severe pressure to adjust, countries with surpluses face no corresponding pressures.1 Keynes’s solution – which was part of the inspiration for the creation of the IMF – was that occasional exchange rate adjustments might be necessary in order to rebalance international credit flows.

A number of commentators have suggested that Germany’s large current account surpluses reflect such imbalances. Paul Krugman attributes the Eurozone crisis in part to Germany’s current account surplus. The capital flows that this current account financed dried up as the crisis unfolded. But the burden of the adjustment fell solely on the Eurozone periphery, which closed their current account deficits, without the aid of Germany where the current account has only increased. In this view, German fiscal surpluses are an international version of the paradox of thrift.2

The IMF (2016) and the European Commission (2016) have both warned of the risks of Germany’s current account surpluses; and both have urged Germany to take actions to reduce its external surplus, for example, by increasing public investment.

While the nature of the Eurozone makes exchange rate adjustments impossible, the IMF reckons that Germany’s real exchange rate is now 15-20% undervalued (IMF 2016, p. 7). The US Treasury has gone so far as to add Germany to its ‘monitoring list’ of countries engaged in ‘unfair currency practices’, even though Germany does not have a national currency (US Treasury 2016).

In contrast, Jens Weidmann, President of the Bundesbank, has argued that German net capital outflows are primarily structural, resulting from Germany’s high level of economic development and ageing population. He also argues that the Eurozone’s common monetary policy allowed slower current account adjustments, thus mitigating the Eurozone crisis (Weidmann 2014). The German economics ministry claims that Germany’s surplus is “a sign of the competitiveness of the German economy and global demand for quality products from Germany”.3

The first question in the October 2016 expert survey of the Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM) and CEPR addressed the question of whether large German surpluses are reasons for concern.4 To focus the question, we asked the experts about its consequences for the Eurozone, but they were free to address wider implications in their comments.

Q1: Do you agree that German current account surpluses are a threat to the Eurozone economy?

Sixty-seven panel members answered this question and a large majority (69%) agree or strongly agree with the proposition. A number of panel members point to evidence of the risks of current account balances. Ricardo Reis (LSE), for example, says that “current account imbalances during 2000-08 played a central role in the Eurozone crisis of 2010-12” (see Obstfeld 2012 and Lane 2013).

Other panel members suggest that German current account surpluses are a symptom of the common European currency. Michael Wickens (Cardiff Business School and University of York) warns that “the main underlying problem is the single currency. Germany’s current account surplus reflects its competitiveness, but due to the single currency, it can’t appreciate against the Eurozone countries with chronic current account deficits. It is all reminiscent of the failures of the Bretton Woods system, which of course eventually collapsed due to currencies becoming misaligned.”

Simon Wren-Lewis (Oxford) agrees that “the surplus represents an undervalued real exchange rate in Germany, which requires more inflation in Germany relative to the rest of the Eurozone”.

Wouter Den Haan (LSE) suggests that the problem is exacerbated by conditions in the Eurozone periphery: “There is a very good chance that the Eurozone is in a bad equilibrium in which consumers do not spend because they are concerned about future earnings and firms are hesitant to hire workers and raise wages because they are concerned about demand for their products. Even if this is not behind the high savings rate in Germany, it does make this increase in precautionary savings more problematic in the periphery.”

A number of panel members (Charles Bean, LSE; Jonathan Portes, National Institute of Economic and Social Research) warn that Germany’s current account surplus is not uniquely a Eurozone problem, but is also large enough to contribute to the low global real interest rates.

The global dimension is also the main counter-argument of the panel members who think that the German current account is not a threat to Eurozone stability. Robert Kollman (Université Libre de Bruxelles) points out that “the German current account surpluses do not represent a threat to the Eurozone economy, because Germany trades more with the rest of the world than with the rest of the Eurozone”.

Pietro Reichlin (Università LUISS G. Carli) caveats his concern about the German current account with the view that “part of the surplus is due to exports to extra-European countries and these benefit some EU peripheral economies that are exporting intermediate inputs and parts to Germany”.

Others do not feel that there are theoretical grounds for concern about the German current account. Francesco Lippi (Università di Sassari) argues: “I do not see why the savings of my neighbour should be a problem for me. Rather, they are a potential source of financing my investment. I do not know a single reasonable model where current account surpluses are a problem.”

Robert Kollman points to research that the key shocks driving the German current account shocks are not central to the Eurozone’s ills (see Kollmann et al. 2015, 2016). Nezih Guner (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) agrees that German current account surpluses are structural: “current account surpluses partly reflect positive supply shocks (such as labour market reforms that lowered wages and made German economy more competitive) and the current demographic structure that results in high savings rates.”

Germany’s Fiscal Policy

With exchange rate adjustment off the table within a currency union, the main policy recommendation to reduce Germany’s current account surplus has been a change in German fiscal policy. Martin Wolf points out that the current account surplus is driven primarily by an increase in the supply of savings of German households and thus reflects insufficient aggregate demand.5 He warns that Germany isn’t carrying its weight in the global economy and has failed to contribute to global aggregate demand.

By this view, the German government’s move to fiscal surplus is a direct drag on the global recovery. The argument is that with interest rates at zero and other governments in worse fiscal positions, the German government should do more to contribute to European and global demand.

The IMF has called on Germany to “focus on raising potential growth and reinforcing rebalancing, which will also support the fragile recovery in the euro area”, including the use of fiscal resources to “boost high quality public investment”.

The European Commission concurs that “weak investment has contributed to the high and persistent current account surplus and poses risks for the future growth potential of the German economy”. The Commission joins the IMF in suggesting that “there continues to be fiscal space for higher public investment, while complying with the rules of the stability and growth pact”.

In contrast, Jens Weidmann suggests that an expansionary German fiscal policy will do little to spur demand in the Eurozone periphery as the import component of Germany public spending is merely 9%. And while Willem Buiter agrees that Germany’s current account surplus is excessive, he thinks that fiscal expansion may not be consistent with German inflation stability and that the European Central Bank should finance fiscal expansions elsewhere.6

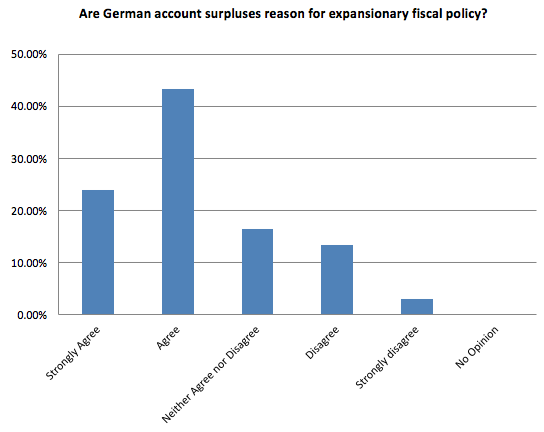

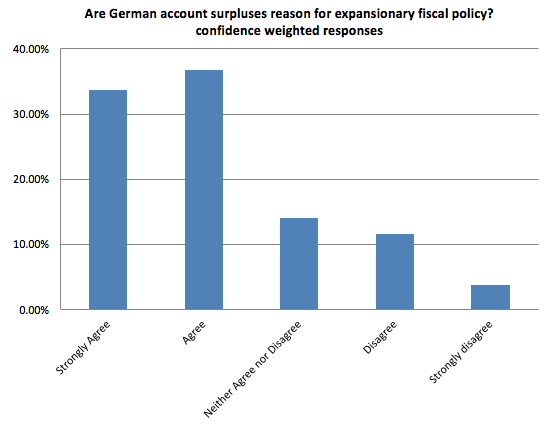

The second question in our survey asked the experts whether the current account imbalance is a reason for the German government to increase public spending. We were not asking whether public spending should increase for other reasons (say low interest rates), although current conditions may – of course – affect the answers given.

The question was explicitly conditioned on the fact that Germany is part of the Eurozone and we asked the respondents to answer from the point of view of the Eurozone. That is, when countries’ fiscal deficits are high, the Eurozone regularly demands that action is taken to reduce public spending: so does it similarly make sense for the Eurozone to ask Germany to increase public spending given its large current account surplus?

Q2: Do you agree that the German government should increase public spending given its persistently large current account surplus and given that it is part of the Eurozone?

Sixty-seven panel members answered this question with a large majority (67%) agreeing or strongly agreeing that the German government ought to increase public spending in response to the current account surpluses.

Panel members who think that the German current account poses risks to Eurozone stability largely supported policy action. The main policy recommendation is an increase in public investment. Stefan Gerlach (BSI Bank) proposes that “more public spending on specific public infrastructure projects that pass a careful cost-benefit analysis and contributes to economic growth would be desirable.”

Sweder van Wijnbergen (Universiteit van Amsterdam) notes that “Germany’s (public capital)/GDP ratio is HALF of the comparable ratio in the Netherlands”. In contrast, Nezih Guner thinks that public investment might be counterproductive: “Public spending on investment incentives or infrastructure, for example, can further enhance the productivity advantage of German economy and can very well make the situation worse.”

Another argument in favour of a German fiscal expansion relates to the asymmetry of fiscal rules in the Eurozone. Costas Milas (University of Liverpool) points out that “the EU Treaty talks about ‘corrective’ fiscal measures when the deficit exceeds 3% of a country’s GDP. There is no similar mechanism in case of a (relatively) big fiscal surplus”.

Ricardo Reis, on the other hand, states that “the Treaties do not put the European institutions in charge of aggregate demand management. Therefore, it makes perfect sense for there to be a pronounced asymmetry between requiring the reduction of fiscal deficits, but having nothing to say about fiscal surpluses.” But he does suggest that discretionary policy is desirable at this point in time: “It seems likely that both Germany and the rest of the Eurozone would benefit from some fiscal expansion in Germany… Given the increase in the primary surplus since 2004, there also seems to be some room to do so.”

A number of panel members support policy action, but not an increase in public spending. Francesco Giavazzi (IGIER, Università Bocconi) and Nicholas Oulton (LSE) advocate tax cuts. In addition, Jürgen von Hagen (Universität Bonn) warns that fiscal action is desirable at the federal level, but not at the state level: “Lander public finances are mostly unsustainable and an increase in spending is not called for.” Wendy Carlin (University College London) proposes increasing incentives for women to participate in the labour force.

Panel members who are opposed to German fiscal action largely point to the limited evidence that such action would reverse the current account surplus. Gernot Müller (Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen) points out that “evidence to date suggests that the link between fiscal policy and the current account is weak. In fact, not even the sign of how a fiscal expansion impacts the current account is clear (see Kim and Roubini’s 2008 paper on twin divergence).”

Evi Pappa (European University Institute) adds: “In my own research, I also show that fiscal consolidation, as a means to induce an internal devaluation in a two country model works, but it affects very little economic activity in the periphery. A more effective way for correcting current account imbalances is transferring resources from Germany to the periphery” (see bandiera et al. 2016).

See original post for references

It’s Merkel realizing Hitler’s dream via mercantilism. The EU is more deadly to the health and prosperity of Europe than the Wehrmacht ever was. Ask all those pensioners in Greece, Spain, Cyprus, Ireland, Italy, the Baltics- oops! ya can’t they’ve committed suicide.

Yes, I got a lot of flack when I made the same point, Paul. It’s Anschluss economics. And Yves is also correct: if we had a functioning supranational fiscal policy framework then Germany’s surpluses could be recycled via the “United States of Europe Treasury” into demand deficient areas, in other parts of the EU, much as California’s surpluses are recycled to Mississippi or Texas’s go to, say, West Virginia. And nobody would give a toss about Germany’s current account surplus, much as nobody in Canada cares if Alberta, or British Columbia run “current account surpluses” with the other Canadian provinces. Of course, as Yanis Varoufakis, Stuart Holland and Jamie Galbraith have long pointed out, you don’t need to go as far as a formal political authority to achieve this result. Existing institutions, such as the European Investment Bank, can be used as the recycling entity and broadly achieve the same purpose. But who prevents that from happening? You guessed it: Germany. Which does lead one to question their political motives here.

Well, only if federal corporate taxes financed spending, and MMTers, and everyone else in this case, know they don’t.

Isn’t the problem that Germany can and does veto such actions? The obstacles are not real or theoretical, but political–thanks to the lack of understanding in Germany and to the willingness of others to accept the German-controlled narrative that surplus is virtuous and debt means only irresponsible profligacy. While that narrative has shifted in parts of the IMF it has not been enough to change the national political discourse in Germany or in other EU countries whose governments and populations have continued to accept the moral framing of government debt being inherently morally bad.

Well, Europe has no shortage of debt at this point. Already they have had the ECB buy the dodgier country bonds and have also gone thru a few exercises in advanced debt derivative sausage making science to convert piles of very smelly debt into something for “investors” resembling investment grade debt. Part of that process included shifting the taxpayer backing of defaulted debt from PIGS taxpayers to “core” Euro taxpayers. But don’t ask me for any more detail than that. When I discern toxic sausage, I just move on and don’t expend any more mental bandwidth than that.

So short of running the Euro presses full bore and spewing out “untethered” Euros in some direction, they need tax revenue. It would be hard to make the case in Europe that individuals are undertaxed. So that leaves corporate tax. Personally, I think the 1st World governments need to get together and come up with a plan to effectively tax multinational corporations. I think so far they have far too successful everywhere in convincing governments they shouldn’t be paying taxes.

What about those Target balances that are accumulating in the German account? These are of course correlated with the current accounts, but can be the trigger that causes the sustem’s decisive crisis.

A huge problem is the lack of public awareness of the implications of German policies. I’ve mentioned this in the company of what I’d considered, educated, well informed people, and the response is, basically ‘oh, yeah, the Germans, they are brilliant exporters and they don’t like debt, that’s why they have a surplus. If only everyone else was as good’. Try to persuade them that the property booms and busts elsewhere in Europe were a direct and unavoidable result of Germanys insistence on trade and current account surpluses and you get a blank look. A key problem I think is the insistence of so many European leaders of trying to get the Germans ‘on side’ rather than directly challenge their hugely damaging policies. But its very hard to shake peoples instinctive belief that maintaining surpluses is an inherently virtuous thing.

It’ll correct itself the hard way as Eastern Europe, Spain and Italy and Asia are now becoming Slavic, Latin and Asian Germanies. Then what? Will the whole world try to export its way to prosperity? This is the madness implicit in the neoliberal globalist agenda. Who is going to be holding the bag? I’ll tell you what happens, Trump comes along and tells them ever so gently to Fk off, And then people accuse him of being a dumb populist? lol

The German propensity/insistence on running current account surpluses and not running expansionary fiscal policies to help its European partners has been a problem for much of the last forty years at least. I would not therefore personalise it by naming Merkel as uniquely responsible.

Of course, as PK points out, an important part of the problem is that many (most?) Germans do not perceive that there is a problem at all.

All of which suggests to me that this situation is likely to continue for a good long while yet. Will it cause the Euro to collapse? Maybe. I will never say that could never happen. Do not, though, underestimate the capacity of the current situation to continue for much longer than many of the doubters expect. I remember back in 2011 being challenged by friends in conversation for holding the view that Greece would not shortly leave the euro.

I did however predict that Greece was in for an unhappy time.

So far, I claim I got that call right.

I agree that there is such momentum in the Euro project that it will last longer than the sceptics suggest. The stubborn attachment of the establishment to the Euro, and the enormous practical difficulties involved in bringing in new currencies will mean that it will continue to survive in its current form far beyond the point where economic logic means it should fail. But without deep reform I believe it will ultimately fail, possibly catastrophically.

I’m trying to imagine. How the German fiscal surpluses could be explained as inherently structural at the national level–is this the case?

Germans also don’t seem to be objecting to high taxation, I wonder why not–it must be the saving=virtue meme like Thatcher’s belief that government finances should be run like household finances.

One of the problems in changing this deeply-held framing is that all citizens are aware of waste and inefficient or corrupt spending in their own country, and rightly want to stop this “bad” spending.

This is a shocking post.

Several experts quoted in this post say the German surplus comes mostly from outside the Eurozone and other Eurozone countries benefit as suppliers to German exports.

If these guys are serious, that means Hanz and Franz wanta pump you up, not beat you up — but you can’t get your lazy ass off the sofa. Or the café chair. Sitting there in some French café drinking red wine smoking Gauloise or there near the Mediterranean sea on a Wednesdy afternoon with your shirt unbuttoned drinking ouzo with your gold necklace and hairy chest. The Porsche Cayenne you bought on credit is your chick bait.. Why work like Hans and Franz. Dumb Germans. Boring. Eating sausage and drinking what? Beer? Their women may be good for farming potatoes but not for sitting in your Porsche Cayenne. Looking hot.

I don’t know about this. Hanz and Franz might have a point! Only you can pump you up. And if you want a Porsche or a BMW well that’s that. if you want to scoot around like a teenager on a Vespa forever, then you don’t need the Germans. Ecce Homo. I think that’s Italian.

This puts Hans and Frans in a new light. Maybe Schauble and Wiedmann are right after all. I never really thought that hard about this, but now, thinking about it for a second, it doesn’t seem as black and white as it did before I read this post. Always learning! That’s the great thing about NC. You read some sleeping pill of a macroeconomic post that only 7 people comment on and you think “Wow. I never realized!” That’s a Hans and Frans workout for me. now back to laying around

If Germany was on the DM, trade surpluses would ultimately make the DM stronger, which would cause their surplus to shrink. But if you and your trading partners are on the same currency, there’s no way to effect that new equilibrium.

By the way, if Germany and Italy were on the DM and Lira respectively, the price of German cars in Italy is more a function of the FX trade between DM and Lira than it is a function of how hard (or efficiently) Hans and Frans are working to churn out goods. It’s the same as saying the reason China has a trade imbalance with the US is because their workers are so cheap. The reason they’re cheap is because China prints currency to keep them cheap (or rather the products cheap).

Bottom line, if Italy was still on the Lira, then their people could be as lazy as they want to be. The wealthy (winners) in Italy will still be able to buy German cars. And Germany can use the Italian Lira they receive for those cars to buy nice Italian designer clothes and wine made by the lazy Italian workers.

Rules under the 1992 Maastricht Treaty limit euro zone member states’ current account surpluses to 6% of GDP. Have read that Germany is now running a current account surplus of 8.5% of GDP. Assuming this restriction continues to be ignored, the trend cannot continue indefinitely, and it won’t. The external accounts of member states will be brought into balance through other adjustments.

With the rising levels of deep poverty and profound social damage emerging elsewhere in the euro zone, seems to me that soon enough some smart citizens in other countries are going to develop some workarounds to the euro payments system IT dilemma that is said to be the key practical impediment preventing re-adoption of sovereign national currencies among member states of the euro zone. That would both enable appreciation of Germany’s currency relatively to their own and also allow them to run fiscal deficits to stimulate their domestic economies; albeit those deficits will likely be above the levels allowed under the Maastricht Treaty.

Seems proponents of teutonic fiscal austerity have either forgotten the old proverb: “You can’t make chicken salad out of chicken shit,” or the damage being inflicted under the policies is coldly intentional:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/10/24/the-eurozone-is-turning-into-a-poverty-machine/

I have no doubt it is intentional, an out of control ruling elite and its favoured flunkeys have long been convinced that the lumpen’s appetites (for honesty,nutrition,health and social security) are an enemy of progress.

I remember reading that the thoughtful chairman of Allianz opined (back in the nineties at least) that the question before them was not whether the gen pop should be squeezed, but by how much.

This was supposedly said at a bilderberg meeting, so it may just be one of those scurrilous rumours that cass sunstein (the male trousers in the power relationship) so deplores.

Looking at ‘the news’ these days though, it doesn’t seem the hardest thing to believe.

Some of the sectors that do benefit from EU funding in the periphery and even non-periphery (France comes to mind)–particularly agriculture and R&D–have and use their national-level political clout in a way that preserves the status quo of EU-level fiscal policy. IOW they will not act to rock the boat as long as they believe they are benefitting from EU largesse.

so how will fiscal spending help lower the trade surplus?

also this article is very confused. it swings between “trade surplus is bad” (a moral statement) to “trade surplus is structural” (a causal statement).

As I see it, Germany has a trade surplus because it is far better at it than the others. The others can complain like hell, but they can’t make those goods as well as Germany. Sore losers, especially the debt/trade deficit addicted Anglo world.

so how will fiscal spending help lower the trade surplus?

Fiscal spending (wisely done) will ameriolate the effects of trade surplus. It can supply spending power to the populations that germany seeks to ‘sell to’.

also this article is very confused. it swings between “trade surplus is bad” (a moral statement) to “trade surplus is structural” (a causal statement).

Not as confused as you are mate, ongoing,constant and instituitionalised trade surpluses drain the recipient and glory the exploiter while promoting pointless production. Germany will re-engineer to produce one shot shampoo sachets for the periphery if that it what it takes to maintain this position.

If you’re going to get all philosophical about the material world we live in; you should recognise that that structural conditions emerge from dominant moral positions.

The dr strangelove tribute act that is wolfgang schauble butresses a structure around his own milieu’s partial moral sentiments.

That is what passes for reality these days.

As I see it, Germany has a trade surplus because it is far better at it than the others. The others can complain like hell, but they can’t make those goods as well as Germany. Sore losers, especially the debt/trade deficit addicted Anglo world.

Germany, I do not doubt, has many fine opticians, you should transfer some your personal surplus to them. Think of it as inward investment.

typical economist bullcrap. when ones position makes no sense, go ad hominem on the questioner.

It can supply spending power to the populations that germany seeks to ‘sell to’.

can and _will_ are very different words. “can” sounds suspiciously like “Hope” – not a good precedent.

isnt the situation the same with china? It has trillions in surplus and trillions in stimulus. How much of that came our way?

Rest is not worth replying to.

I’m not an economist, but I think your ideas firmly support the ‘typical bullcrap’ ie

Hard working teutons supporting feckless peripherals

You are bang on about the difference between ‘can’ and ‘will’.

It had never occured to me before.

I can see it now and will respect it in the future.