Yves here. As Pilkington’s post makes clear, the loanble funds theory, which is the foundation of the Fed’s failed stimulus policies, refuses to die.

Pilkington gives one refutation in his post from the Bank of England, but let me give a layperson’s version from a 2012 post:

Bernanke is also a firm believer in the discredited “loanable funds” view, that if you make put money on sale by making interest rates low and credit readily available, businesses will take advantage of it and borrow and invest. But that’s just silly. The cost of money is a secondary consideration in investing. The primary one is: will there be enough buyers for your output and will they pay what you need to charge to make the project work?

I do need to add one qualification: there is one type of business where the cost of money is a huge consideration in whether or not to invest: levered financial speculation. So it should not be surprising that the one concrete effect of money on sale is booming asset prices.

And here is one of many shreddings of the loanable funds theory from a Respectable Economist, in this case Servass Storm:

Mario Seccareccia’s note last week did a great job of showing how the Summers/Krugman “liquidity trap” argument is just the old Wicksellian loanable funds market, which has acquired something like the status of a folk theorem in economics. “Within this neoclassical theoretical box”, the note states, “there is only one solution to move the economy out of secular stagnation. One must boost the Wicksellian “natural rate” by strengthening expectations of return.” This could be done, as the note argues and following Wicksellian logic, by a policy of negative real interest rates (amounting to a fiscal subsidy on borrowing) which might do the job of triggering an asset bubble.

What the note does not state so clearly, however, is that Wicksell assumed that the loanable funds market operates in a situation of full employment, i.e. income would be at the full employment level. The (natural) interest rate would then balance savings supply and investment demand, only affecting the composition (but not the level) of full-employment income. Keynes argued, of course, that it was possible for investment and saving to be equal at any level of income, which implies that the equilibrium rate of interest might be consistent with any amount of unemployment. Applying Wicksell’s loanable funds model in a blatantly non-full employment context, as Krugman and Summers are doing, is – therefore – a red herring, distracting attention from the real issue, which is: unemployment due to lack of demand.

Now to Pilkington’s effort to put this economic zombie to rest.

By Philip Pilkington, a London-based economist and member of the Political Economy Research Group at Kingston University. Originally published at his website, Fixing the Economists

The Rethinking Economics conference in New York took place over the weekend. Anyway, Paul Krugman was on a panel with James Galbraith and Willem Buiter. The panel was interesting in and of itself. But what really caught my eye was when Krugman was confronted by an audience member on his support of NAIRU, the loanable funds theory and the theory of the natural rate of interest.

The audience member who asked this question was Rohan Grey, a friend of mine who runs the Modern Money Network who helped co-organise the event. You can see the question and the response in this video clip.

I don’t really want to get into the question of NAIRU too much as this would take us too far off track. But the other two questions provoked an interesting response from Krugman. First of all, he simply asserted that the loanable funds was true. Then he went on to assert that the natural rate of interest was true. “Clearly,” he said, “there is always some rate of interest that would produce more or less full employment”.

Let’s take each one first. Because Krugman is wrong on both counts. In his textbook co-written with Robin Wells, Krugman outlines the loanable funds theory in the form of the money multiplier. In the video linked to above he alludes to the fact that this may break down in what he calls a ‘liquidity trap’ but that in normal times it is nevertheless true. This is simply false (Krugman has also misunderstood the concept of the liquidity trap but that is a story for another day). The Bank of England released a paper earlier this year which stated crystal clearly that this misrepresented how money is created.

The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks:

• Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits.

• In normal times, the central bank does not fix the amount of money in circulation, nor is central bank money ‘multiplied up’ into more loans and deposits. (p1)

If that is not a clear enough refutation of the loanable funds theory, here is another:

The vast majority of money held by the public takes the form of bank deposits. But where the stock of bank deposits comes from is often misunderstood. One common misconception is that banks act simply as intermediaries, lending out the deposits that savers place with them. In this view deposits are typically ‘created’ by the saving decisions of households, and banks then ‘lend out’ those existing deposits to borrowers, for example to companies looking to finance investment or individuals wanting to purchase houses. (p2 — My Emphasis)

When I raised this point on this blog before Krugman did a blog post the next day saying that the Bank of England paper said nothing that he did not already know. In the same blog post alluded to James Tobin’s work on money creation.

If Tobin actually did make the case for endogenous money, and I am not entirely convinced of this, but if he did then he overturned the loanable funds theory. If Krugman states that he adheres to the view put forth in the Bank of England paper which he claims he learned from Tobin then why does he continue to endorse the loanable funds theory when asked about it? The two views are mutually exclusive and the Bank of England makes this clear in no uncertain terms.

The fact of the matter is that Krugman is self-contradictory on this point. And self-contradiction is the surest sign that one is simply incorrect or has not thought through a particular point on any great amount of detail.

Now, how about the idea that “there is always some rate of interest that will lead to more or less full employment”. This idea is grounded in the notion that there is a mechanical relationship between investment and the rate of interest. But anyone who has read Keynes — especially Chapter 11 of the General Theory — knows that this is not the case. Rather investment is driven primarily by the expectations of investors. The rate of interest plays an entirely secondary role — if it plays a role at all given that most studies have shown that businessmen do not think about the interest rate when they make investment decisions.

Tied to this last point, mainstream economists have now recognised that monetary policy actually works through some rather odd channels; its effects are not felt through the investment channel as such. So, even reading the recent literature on monetary policy from some mainstream economists makes clear that it does not work through the investment channel as is laid out in the ISLM model that Krugman constantly endorses.

But let us be less abstract and bring this discussion down to earth. What would likely happen if the rate of interest went substantially negative? Would investment and thus employment really increase? I don’t think that it would. Far more likely that, in a closed economy, money would flee safe assets as liquidity preference fell and would rush into riskier assets. This might just fuel a speculative credit bubble.

In an open economy money would probably partially run into the speculative financial markets and partially flee the country. This latter tendency would drive down the currency. Given that we must already assume some inflation since we are talking about negative real interest rates this could lead to a hyperinflationary collapse.

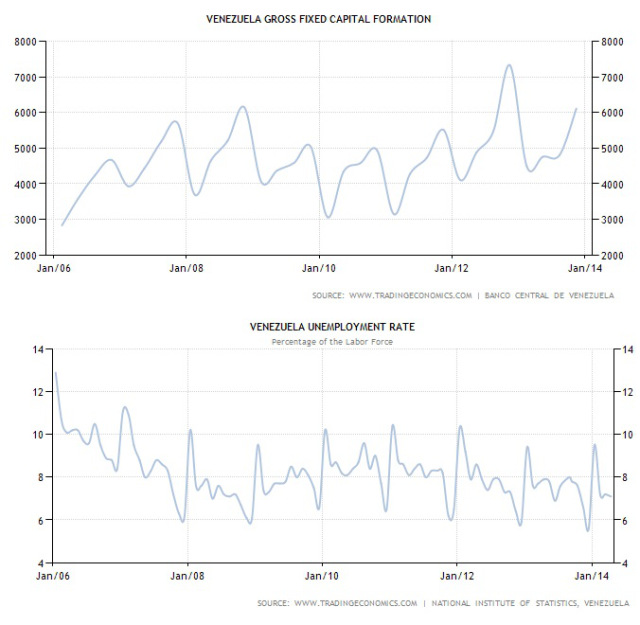

This is precisely what we see today in Venezuela where, as I have noted before, substantially negative real interest rates have resulted in a stock and housing market bubble. Meanwhile investment has not shot up and unemployment has stayed on trend and rather high (note that the significant negative real interest rates were enforced around the start of 2013).

Substantial negative real interest rates of around -20% to -30% were brought into effect in the second quarter of 2013. But the upswing in investment you see in the above chart occurred prior to this in the final quarter of 2012. There is absolutely no evidence that significant negative real interest rates have increased real investment or driven unemployment down in Venezuela. All they have done is led to massive bubbles in the financial and housing markets and to an enormous attempt by capital to flee the country which is reflected in the black market rate for dollars soaring. If there were not strict capital controls in place there is no doubt that Venezuela would be experiencing hyperinflation today.

What does this mean for policy in the advanced economies? If central banks in these countries were able to generate real negative interest rates — and I have outlined how they might do this before (Krugman says that it is impossible… wrong) — it is likely that this would simply generate stock and housing bubbles. Real investment and unemployment would probably not be much affected. But when the bubbles eventually collapsed this would likely have negative effects on both.

Krugman’s monetary theory is almost entirely wrong. He flip-flops on the loanable funds question and he is simply wrong on the question of a natural rate of interest. He also holds to an incorrect view of what a liquidity trap is that he picked up from John Hicks. While it is extraordinarily unlikely that he will give up on these ideas — he has dug in far too much now to concede these points and he seems unwilling to even openly debate them — I only hope that his errors will help to ensure that others do not make the same mistakes.

Indeed Paul “Magneto Trouble” Krugman is very wrong about monetary theory … But he is in keeping with the privately owned and operated Federal Reserve wherein Mr Krugman’s allegiance resides.

The fact is that these contrived dogma are for the benefit of a Central Bank that will protect the banks before it protects the citizens or the country. That’s their mandate. Would they lie about such matters … of course.

Congress controls the Federal Reserve, not private concerns. But Congress has refused to do its job of creating fiscal policy, which means running the country financially and responsibly, so the Federal Reserve (just a payday loan company with fancy digs) is left to use its meagre monetary policy tools to take up the slack. The fault is with Congress and its general lack of knowledge of reserve accounting. Aim your arrow there. Or at the American people who elected these know-nothings.

I meant running the country “fiscally,” not “financially.”

Mr Krugman likes wading into contradictions, but heaven forbid someone cornering him on them…. I noticed Stiglitz challenging his assumptions on Scotland. Mr Krugman, siding with the No crowd, warned us of disaster if Scotland goes it alone with the pound. He found like minded economists to back his logic. Stiglitz acknowledges potential problems buts says folks should ignore the scaremongers (read: Krugman). Its more than just economics at stake. Many Scots are fed up with Tea Party Torys slash and burn governance, something Krugman ignores. Scots want to pursue policies that are ‘right’ for the people of Scotland.

Sometimes you have to try other strategies because the economics wing can be very myopic in its prescriptions.

Phil if you ever see Professor Krugman at a conference you really owe him a beer, for all these posts. Why is he the “The Most Talked About Man on the Planet” (TMTAMOTP). Obama must be jealous. It sounds like an Inca Chief. Tomtamotop, the Pyramid King! No pun intended. If I was Professor Krugman I’d have my interior decorator collect about 10,000 critiques of my thinking in newspapers magazines and internet posts and plaster them on my office wall behind shellac as a form of artistic design. Then I’d laugh, hysterically. It’s like a literary “selfie”. TMTAMOTP rules! It’s all a mental disorder, all this Newtonian nonsense. You yourself are coming under the influence of “the disorder”. It happens to almost anybody who gets near the black hole of economics and starts arguing with it. It’s like Odysseus there on the island with his crew eating that lotus flower.

Prep and then dive in crwazzyman….

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2014/09/links-91514.html#comment-2308880

Haha! Yes, I agree. It’s true that the critiques are really quite equivalent to a sort of fan mail. I personally don’t even mind Krugman that much — although he would do a lot more for his legacy if he engaged in these debates. At the moment he risks going stale on his perch at the NYT.

However, Krugman is terribly influential. A lot of young economists listen to him for research advice and for how to think about the economy. Correcting his errors allows one to start a debate with these people.

That is why I say that I don’t care about changing Krugman’s mind — or Nick Rowe’s, or any other of the mainstream greybeards. The key is to target people with no intellectual sunk capital. By engaging with Krugman you can do that.

Economics, like physics, change one death at a time?

Obama must be jealous. How about furious, that not every iota of attention isn’t focused on himself. To make sure that doesn’t happen anymore, perhaps WW III will be started.

NPD. Narcissistic personality disorder. We have the fucked up thinking of a narcissist sitting in the White House.

I pray that I am wrong.

You claim Krugman and like-minded economists are wrong. You’re model predicts speculative bubbles and hyperinflation. So where is the evidence that this is occurring in the US? You have provided no evidence that your model has predictive power. Krugman claims the lack of inflation supports his model. If you can show another speculative bubble, then you can claim that this supports your model, but you also need to explain why hyperinflation hasn’t appeared too. Trying to undermine a theory without showing evidence that it is more explanatory than the old theory has little merit.

Did you even read the article? The author is talking about a hypothetical scenario (a sudden jump to substantially negative interest rates), which he predicts would result in speculative bubbles and hyperinflation. It is categorically not a prediction for what is currently happening in the US.

The lack of inflation* in the US does nothing to support Krugman’s entirely false understanding of money creation, and it is not even a matter for model-based predictions. It is, very simply, the mechanics of how banks create money – and Krugman has it completely backwards.

“You’re model predicts speculative bubbles and hyperinflation.”

Um… I think you need to reread the piece. Try again.

“This is precisely what we see today in Venezuela where, as I have noted before, substantially negative real interest rates have resulted in a stock and housing market bubble.”

That is what you stated, using Venezuela as an example. The implication is that QE should lead to -ve interest rates via inflation (appearing as speculative bubbles) but no credit creation through business investment. Since we’ve had QE, can you show where the inflation or speculative bubbles are? I grant you that you play the hypothetical: “If central banks in these countries were able to generate real negative interest rates“, to which anyone can counter with other hypotheticals.

Um… no. I don’t have a “model”. And if I did it would not “predict hyperinflation” in the US unless the US decided to run negative real interest rates of about -20% to -30% without capital controls in place.

I don’t have a “model”

Isn’t this exactly what Krugman constantly complains about? Without some model of what happens, one cannot make testable hypotheses. Economists like to claim that they are doing science, and are especially prone to playing with math. If scientific approaches are to be used, then hypotheses must be testable and the predictions clearly connected to some model (not necessarily formal). Otherwise it just becomes squishy. Or as The Economist once said, ideas need to be “crunchy”.

So to get back to your piece, the assertion that “loanable funds theory” as a relevant mechanism is false requires that you have a model (of some sort) makes a prediction that diverges from Krugman’s so that it is testable. If the prediction is that the outcome is the same, then it doesn’t tell us anything (which doesn’t prove Krugman right either). OTOH, having a model with a testable prediction that proves correct while Krugman et al are proven incorrect would be valuable. If Krugamn stands by his claim that this would result in his rethinking his models, then you would have won your argument (with the proviso that more tests are needed) and economics moves forward.

You don’t need a model. That is what Pilkington is saying. You have reality as proof. You have how it operates today. The reality is that loans create deposits. Out of ‘thin air’ based on underwriting and the creditworthiness of the borrower. Banks are not allowed to loan out their borrowers’ deposits by law, and they can’t loan out reserves.

Krugman’s loanable funds theory assumes a money multiplier. [You deposit $100, the bank keeps $10 then loans out your $90. The next borrower’s bank keeps $9 then loans out his $81. The next borrower’s bank keeps $8.10, then loans out her $72.90. Etcetera.]

The money multiplier hasn’t existed since the days of the gold standard. It does not exist.

You, like I, are probably wondering how Krugman could be so dumb, if the money multiplier doesn’t exist, but he is. We clung to the earth-centric view of the heavens for 1500 years, and ‘intelligent’ men put people to death who challenged it.

“… but you also need to explain why hyperinflation hasn’t appeared too.”

Because the newly created money has not been spread evenly throughout the economy. It has gone primarily to “goods” and “services” that are (or can be) highly financially engineered. Equities, MBS, commodities. Hyperinflation is not yet extant because all that money is propping up asset prices and not boosting wages. A little bit of inflation is transmitted through to the general economy via the commodities – those notoriously volatile food and energy prices.

Good answer.

Bottom line: these days, there is no opportunity cost for holding cash. What is anyone missing out on? What investment is reasonably assured of making a return in this market?

Once upon a time, our central bank might have guesstimated the amount of money an economy needed to get all of its work done (unemployment target) and stay on budget (inflation target), and adjusted the supply accordingly. No more. They can print as much cash as they like because none of it goes towards doing either of those things.

This implies that money and capital (the stuff we use to get our work done) are fundamentally de-linked. I think the inescapable conclusion is that our “capital markets” stopped allocating capital a long time ago.

Eh, I’d say the flaw in monetary theory today is in believing that it is a discipline distinct from political economy, that money itself matters that much.

Money is just a tool of power, nothing less, but nothing more, either. We are living in the midst of a crime spree.

It’s not that Krugman is right or wrong on interest rates or bank deposits or whatever. It’s that the debate is irrelevant. This fixation over money is fundamentally unhealthy.

Crooked banks don’t create money. Government gives it to them. This is such an elementary concept that to confuse it suggests willful ignorance to what is actually happening.

Please reread the post. Banks do create money. They create deposits by making loans. Deposits are money. As the Bank of England notes, most of the time, central banks don’t meddle in this process.

Yves, I think this is one of the fundamental communication barriers for how MMT is being used in political rhetoric.

MMTers can’t have it both ways, saying on the sectoral financial balances that the private sector needs the public sector, but then on banking, saying that banks create money. Those two claims are not coherent when taken together. Either the private sector can create its own savings, or it can’t.

At any rate, in lay speak, it simply flies in the face of reality. If banks could create money, they wouldn’t need the government to bail them out(!). To say that the government lifeline is only used when it’s needed is simply to observe how lifelines work.

washunate,

You are absolutely correct. There are incompatible definitions of money at work. Lay people think that money is the stuff you earn and the stuff you save up over time. Economists think specific assets like bank deposits are money. But while banks create deposits when they lend, they do not create income that adds value to anyone’s balance sheet. That income is the real “money” and it can ONLY come from govt spending. Accounting “losses” on the public side of the balance sheet network.

Of course banks can create savings; they just can’t enable saving in aggregate.

There’s not contradiction, only loose reading by yourself. MMT says that bank loans create deposits which are both savings and money. However bank loans also create liabilities for the debtors.. So, a bank loan creates no net savings.

Deficit spending,on the other hand, does create net savings. Not immediately “money” savings, but savings in the form of Treasury securities,net financial assets (NFA). What’s contradictory about this picture?

The short answer I’d offer is that ‘loose reading’ is exactly the issue. These are esoteric, academic debates about semantics, meanings of words so far removed from normal conversation they carry no meaningful meaning. That’s the political problem, the communication. Because it means consensus can never be reached about the opinion parts of MMT, such as exactly what kinds of jobs a JG/ELR should do or how such a system should be managed. To a more cynical reading, it sounds like a used car salesman, purposefully leaving out valuable information to deceive the listener. Authenticity and clarity I think have become under appreciated values as the fraud and mistrust it brings has cast its shadows over all our nation’s institutions.

***

“MMT says that bank loans create deposits which are both savings and money.”

Have you spent so much time in this that you don’t hear that statement anymore? The word create, in lay speak, means to make something new, to bring about somethingness from nothingness, existence from nonexistence. What you are describing is something entirely different, changing one thing into another. That’s called transformation, not creation. Banks take potential energy and turn it into kinetic energy. They don’t create energy. Look at your very next sentence. And then there’s savings and money, words that have very different meanings outside of monetary theory.

“However bank loans also create liabilities for the debtors.. So, a bank loan creates no net savings.”

Um, duh???? Who thinks banks do anything other than that? That’s what a bank does. It transforms the credit money of a borrower into currency money of the state. The bank does this because one of two things also happens:

1) the borrower promises to obtain money in the future and give it to the bank, or

2) the government promises to give money to the bank.

This conversation requires such a tangled morass of definitions for words like create, money, and savings, that it carries no value in conversation outside of the carefully crafted confines of the original construct. Which of course is precisely the defense MMT offers when it is critiqued. You don’t understand, you need to read more, you’re taking things out of context, that’s a loose reading. That may be quite effective preaching to the choir or railing against establishment academics or as a grant-seeking tool or something (and indeed, this is one of the shortcomings – Wray and the rest are so used to battling the crony rightists they seem unprepared to actually deal with authentic perspectives from other angles). But berating detractors is a counterproductive political strategy. I know personally I have become very interested over the past couple years about what where exactly MMT is heading, because it seems such a natural fit for the authoritarian state of the past couple decades. Dick Cheney is the quintessential MMTer.

“Deficit spending,on the other hand, does create net savings.”

This is the heart of the issue. This is not about being ‘right’. Rather, it’s about being irrelevant. That’s a much different critique. Of course deficit spending puts savings in the pockets of the private sector. That’s why people hate it whenever it is used to put money in the wrong pockets! Why does MMT think this is some kind of brilliant insight?

When politicians say there isn’t enough money to fund something, what they are saying is that they don’t want to spend money on it, not that there literally aren’t enough 1s and 0s to make the electronic transfers through our banking system. This is such an obvious point that it suggests a desire to remain buried in the sand, purposefully avoiding the actual issues. Which are, give or take, of three broad types.

1) Better ways to spend the money. This approach desires economic activity, but a different kind than the current system provides. In short, we confront a distributional problem, not an aggregate problem.

2) Better environmental sustainability. This approach says that economic activity is secondary to the health of our planet. The only home we have for the foreseeable future, after all.

3) Better values. This approach is openly hostile to the materialism and consumerism and wastefulness of American culture. Less is more.

I’m much less radical than many critiquing our system, because I’m mostly in camp 1. But I know enough about the frustration in our society to know that 2 and 3 are real and legitimate critiques. I’d say they are gaining traction, not losing it.

From the Tiny House movement to evangelical Christians to Millenials with no stake in our present system, there is broad dissatisfaction with the greed and just plain dishonesty of our leadership class, of upper middle class suburbia, of the police state and general oppression and injustice. People want plain language that treats them as adults, and MMT quite simply doesn’t do that. It instead creates (see that word?) these technical definitions that serve the purpose of making it difficult to critique the substance of what is being discussed.

Or perhaps to say it differently, Krugman has totally trolled you guys on these matters :)

Who cares about the loanable funds theory? It’s just money.

“Who cares about the loanable funds theory?” Er, people who don’t like to be fed bullshit?

The MMT claims are perfectly coherent, although some presentations can interfere with understanding that.

Banks create money: bank-money = bank credit. States create money: state-money=state credit. Calling bank money “credit” and state money “money” just because state credit is more moneyish, more negotiable, is extremely misleading and just plain wrong. In modern societies, the state’s money is on top of the pyramid of money. States bail out banks. But there is no fundamental, logical reason that this be so, and in the middle ages, bank money could be more moneyish, higher on the pyramid than state money. Banks could bail out states.

The private sector can create its own claims on the private sector, and these are a perfectly ordinary form of savings, e.g. loans from a bank, bank deposits.. The private sector can’t create its own claims on the public sector, can’t create state money other than by counterfeiting.

MMT insists that monetary theory is part of political economy rather than distinct from it. But that money doesn’t matter very much, that there is any way to understand modern political economy without monetary theory is absurd. It means not understanding the details, scope and size of the crime spree. Ignoring the central role of money is unhealthy. Which is why mainstream/ neoclassical economics systematically ignores money.

Crooked banks don’t create money. Government gives it to them. Crooked banks create bank-money, not state money. Crooked governments do effectively give state-money to crooked banks by backing their bank-money, by bailing them out with state money, yes. But there is a difference between a vaguely right musing and a precise, correct, consistent description.

I call bank “money” credit and state money money, but not because it is more acceptable than other forms of payment. It is because the state money, which is created via net public spending, is what constrains the value of private sector income and savings balances.

When ordinary people think about banks creating money, I believe that they believe that someone is receiving the money that was created as INCOME, When it is really CREDIT that they received. That is why I argue that we should use the word money in a way that is consistent with the concepts of income and savings, as opposed to credit which is about lending and liquidity.

Like I said, it is a bad idea – for theoretical purposes, for understanding. State money is just state credit. There is no conceptual difference with bank money/credit that merits another word. The basic concept is credit, not money. Money is defined as a kind of credit, which is a relationship, not a thing. Thinking of money as basic leads to thinking of money as just a thing, leads to the commodity theory, neoclassical econ etc.

If state money is not on top, is it “what constrains the value of private sector income and savings balances”? Don’t really understand you here.

But while banks create deposits when they lend, they do not create income that adds value to anyone’s balance sheet. Hard to agree with. The deposit that the borrower gets when he borrows certainly does add value to his balance sheet. Why on earth would anybody sign for a bank loan if he didn’t get something of comparable value in return? He may then spend the bank deposit, say to buy a house. The seller now has “the” bank deposit, created by the bank’s decision to lend to the buyer. Certainly is (capital gain) income to the seller – the IRS thinks so, sees the added value to the seller’s balance sheet.

I think we’re stuck in arguing semantics. Brian’s point is about net income that is received by the private sector when the government sector runs a net fiscal deficit. When banks create money via lending, yes, it does trigger increased economic activity (more production, more consumption); but that stems from credit, not income. In the sense that, by borrowing, you consume more today with the promise of consuming less than now and less than normal in the future. Private debt growth will ultimately lead to private debt deflation – to lower incomes (because of bank payments), to lower consumption, to lower sales, to lower production and fewer jobs.

All horizontal transactions net to 0. We want the net to be positive, so we require a horizontal transaction (government crediting us with more money via its spending than it debits via taxation).

I think a distinction between base money and bank money should be made. Especially since the later has the greatest share. In the UK, 93% of all money comes from the finance sector. 7% from the government sector.

As for “not adding value to anyone’s balancesheet” that statement is true only in net terms, when one looks at the nongovernment sector.

Edit to my previous comment. I meant vertical transaction vis-a-vis the gov deficit. My bad.

Here’s why I think a distinction between ‘base’ money and ‘bank’ money should be made. Bank money, that is, money created via lending HAS to be extinguished at some point in time. Base money, that is, net fiscal deficit funds that remain in the private economy as net financial savings DON’T HAVE to be extinguished at some point in time. The money supply grows when private debts are contracted (when banks create money); and it contracts when those private debts are paid off or are defaulted upon (when deposits get destroyed).

It’s like the difference between economic activity coming via monetary stimulus vs fiscal stimulus. The former is stimulus from existing income (leveraging). The later is stimulus from higher income (non-leveraging).

“Banks making loans and consumers repaying them are the most significant ways in which bank deposits are created and destroyed in the modern economy.” (McLeay, Thomas, & Radia, Money creation in the modern economy, page 3)

You all know this; so I think it’s a (I like this better) choice between preferred semantics.

Base money, that is, net fiscal deficit funds that remain in the private economy as net financial savings DON’T HAVE to be extinguished at some point in time.

Illustrates my point: Correct semantics, correct terminology is essential. For the italicized statement is factually false. State issued base money “has to be” and is extinguished at some point in time. Exactly in the same way that bank money “has to be” and is extinguished. Any form of money, of credit has worth only because it is accepted, and for all practical purposes this means it is accepted ultimately, eventually by the issuer, at which time the money disappears. Works the same for states as for banks.

Modern states (or banks) ceaselessly issue and extinguish vast sums of money. They generally deficit spend, issue more than they extinguish. But this does not mean that there is some lump of “net fiscal funds ..” that doesn’t get extinguished eventually. With negligible exceptions of no importance (lost coins, abandoned bank accounts) everything gets extinguished eventually.

Both bank money and state money work like a bathtub with a faucet and a drain. That the bathtub fills up with ever more water does not contradict each water molecule spending only a finite time in the tub on average before going down the drain. There is no “permanent water” in the tub, just as there is no permanent money. The value of money is its impermanence.

Net financial savings don’t have to be extinguished over time; this was my point – not that they can’t be. In order for that to happen, to errode financial savings previously accrued by the non-government sector, the government would have to run fiscal surpluses.

The difference is simple.

The bank grants me a loan, and I’ll have to pay back the principle and the interest on it.

The government runs a fiscal deficit, and I don’t have to pay that income money back to the government. After the tax bill is covered, the nongovernment sector still has a surplus left in gov money.

A government fiscal deficit makes me the nongovernment sector wealthier in net financial terms. A bank loan doesn’t makes me the nongovernment sector richer or poorer in net financial terms.

Net financial savings don’t have to be extinguished over time; this was my point – not that they can’t be. …. The government runs a fiscal deficit, and I don’t have to pay that income money back to the government.

My point is that such statements are ambiguous: but they are either false or meaningless. And using one interpretation for banks and another for governments provides no evidence for a conceptual difference.

False on one reading because in practice, any money in the net financial savings will be and practically speaking must be extinguished, even if the net financial savings grows indefinitely by deficit spending. The government is going to tax away every dollar it deficit spends eventually, even if it never runs a surplus.

The other reading is caring only about the increase in the aggregate. Then it is meaningless because the statement is true just as much for banks or even private companies as for governments. Banks, or the banking/financial sector or even very stable companies like utilities can indefinitely run deficits. I could just as easily and truly say “Net bank liabilities don’t have to be extinguished over time”. So this is therefore not a marker of a (nonexistent) conceptual distinction between bank and state money.

A government fiscal deficit makes me the nongovernment sector wealthier in net financial terms. A bank loan doesn’t makes me the nongovernment sector richer or poorer in net financial terms.

No, a bank loan does make the nonbank sector richer in net financial terms. (netting over the bank vs the nonbank) That is what the increase in bank deposit liabilites means after the lending occurs. Remember, I am trying to explain that there is no difference between bank and state money of the kind claimed. The error is that netting over gov vs non-gov applied to bank money (instead of netting bank vs nonbank) assumes what you want to prove.

Ok, you say there’s no conceptual difference. I think you’re arguing semantics here. Yes there is; just as it is in practice. Otherwise economists wouldn’t keep track to see how much money in the economy is actually government created money, how much it’s bank created money.

I was talking about financial savings in net terms. Whether you pull the line at a fiscal day, month, quarter, or year. All transactions within the nongovernment sector balance out to 0. In order for the nongov balance sheet to be positive or negative, the gov sector’s would need to be in a deficit or surplus.

The government debt is tax-credits outstanding; it’s the movement between 2 buffer stocks: the currency and reserves.

Please read what I actually type. I said that NET financial assets in a given time-span are NOT extinguished; otherwise, they wouldn’t be positive net financial assets to begin with. Yes, of course government takes money away from the nongov sector when it taxes – but the process is different from the kind of money destruction that happens in the banking system.

For banks demand payment of the entire loan + interest. Governments, usually, don’t do that in their fiscal behavior. They always destroy less money in taxation than they’re creating via public spending.

Money from income and from loans is money, but income and loan are not the same in the sense that income is not repayable in principle + interest to the government, unlike the later owed to the bank/s.

You cannot compare fiscal deficit spending with a bank loan. Even if it’s the same money, it gets created by different rules. Sure, we use the same logical reasoning when talking about the two. We don’t apply a cartesian logic to one, and to the other a lobachevskian one, for instance.

Hell, this is the argument that many heterodox economists make when talking about the modern banking system (endogenous money). That it’s not a sovereign fiat regime; that private banks have access to that prerogative.

I understand Brian’s reasoning for saying what he says; and I understand yours and that of Fullwiler. As I said, semantics. For in practice, money I get from a gov paycheck and money I get from a bank’s paycheck or loan is the same.

Have a nice day.

Ok, you say there’s no conceptual difference. No, I am saying there is no conceptual difference of the kind you and Brian think there is. This is a crucial point of MMT. See Mitchell-Innes and his commentators. The sole fundamental difference is that bank money and state money are relationships with different entities. This a very big difference, founded in the fundamental fact that only MMT emphasizes: that money is a relationship, not a thing.

Yes, of course government takes money away from the nongov sector when it taxes – but the process is different from the kind of money destruction that happens in the banking system.

No, it is not. It is absolutely the same process. See Mitchell Innes et al. MMT , Wray adopts Tooke’s word “reflux” to mean banking or government destruction. Because they are essentially identical.

For banks demand payment of the entire loan + interest. Governments, usually, don’t do that in their fiscal behavior. They always destroy less money in taxation than they’re creating via public spending.

No, governments do “do that” . The second sentence is not the appropriate comparison. The parallel to banks getting principal plus interest later is governments revenue increasing later (while usually running a deficit later also, so later spending is yet more).

Money from income (state spending) and from loans are not “the same” only because they are part of different transactions. Bank lending is more complicated, “more financial”, there are 2 financial instruments exchanged. In government spending or taxation, typically “something real” is exchanged for only 1 financial instrument.

You cannot compare fiscal deficit spending with a bank loan. Even if it’s the same money, it gets created by different rules. Nope. There is only one way to create money: By making a promise, a declaration of indebtedness. Comparing deficit spending and bank lending correctly is a great virtue of MMT = careful, correct, intelligible accounting.

Again, I am not saying bank & state money are the same. No more than dollar bills in my pocket is the same as dollar bills in your pocket.

These are pretty crucial applied MMT points. Understanding the “semantics” is everything, the hard part, something perilous to ignore. I once vaguely thought as you and Brian do, until I thought it through more.

I think we’re stuck in arguing semantics Stuck? That is my aim. :-) Confused and confusing semantics leads to absurd results.

Private debt growth will ultimately lead to private debt deflation.

Not necessarily. Not as a matter of logic. True merely in practice, not in theory. You can have long expansions of indeterminate and indeterminable length driven by private debt growth. If everybody lends and borrows wisely – an impossibly big if – there is no accounting reason why the expansion cannot go on forever, and why it cannot lead to everyone producing and consuming more. Government money is crucial as a stabilizer, not as an absolute necessity for economic activity. As Warren Mosler said, in theory it could all be just one penny (of state money / national debt) whizzing around. (The whizzing around being the creation and destruction of bank money of course.)

I think a distinction between base money and bank money should be made.

Yes, of course. Getting this right is a big part of MMT. But you have to make the distinction correctly. Base money and bank money are different, but not because of some mystical difference we decide to then not talk or speak about. The difference is that states issue state money. State money is a relationship with the state. Banks issue bank money. Bank money is a relationship with a bank. That is all.

They are both just instances of the concept “credit-debt relationship” – which is how they “are the same”. With bank money, the bank is the debtor, with state money, the state is the debtor. That is the only intrinsic, conceptual difference. Of course they can have different values, just the same way dollars and pounds can change relative value.

The deposit that the borrower gets when he borrows certainly does add value to his balance sheet. Why on earth would anybody sign for a bank loan if he didn’t get something of comparable value in return?

There IS a critical conceptual distinction which makes bank credit a separate concept from state money. When I borrow from a bank I receive marketable currency in my account, but my net worth (my balance sheet value) does not increase because I sold a liability for the same amount to the bank. When the govt spends and agrees to “lose” the money that is spent, it does add positive net value to the balance sheet of the payee. This is only possible because the state is able and willing to run a perpetually increasing negative balance of money. The same is not true of a bank. Banks are set up to be money making entities.

In order for one person to make money, another person has to lose money.

Brian Andersen: When I borrow from a bank I receive marketable currency in my account, but my net worth (my balance sheet value) does not increase because I sold a liability for the same amount to the bank.

There is no distinction here. This makes bank borrowing different from a “helicopter drop” – (from the state or from a bank) but that is a difference of different transactions, not of what is being exchanged in the transactions.

Private sector entities can and do borrow directly from the government, the state can be their bank, and it gives them state money directly of course. By the above logic, this would make that state money different from other state money. It isn’t.

Bank money is different from state money. Just the same way Citibank money / deposits is different from Chase Manhattan money / deposits. No other difference, except the state is much, much bigger, its money intrinsically more valuable. So much bigger that we use state money as the measure of all other money nowadays, and for most of history. But not always, not necessarily by logic.

Banks can indefinitely have more and more deposits, more and more liabilities. Even private companies can have ever increasing debt, if they are solid enough. It is possible that a bank or private company (usually a utility) be well run and safe enough for this to happen. And such situations can last longer than some states and their money have existed.

Brian

We think it is important to understand the difference between the two, but one is not more important or more “money-ish” than the other. The difference between credit money being saving but not net saving and state money being both does not mean both aren’t money in the sense of the entire economics profession’s definition of money.

But you are making up your own definitions of money that are not the same as anyone’s anywhere at least that I’ve seen, and certainly not the same as any other economist’s that I’ve encountered. This sort of redefining to fit your own purposes can lead people like Washunate to completely misinterpret and misrepresent MMT (as he did above and does regularly on this blog).

Overall, feel free to have your own definitions, but please don’t use them in MMT’s name or suggest that MMT subscribes to them, because we don’t. Thank you.

Best,

Scott Fullwiler

Thank you for your reply.

With respect to the specific point you made, I would not agree that credit created by banks constitutes saving because I have savings as the difference between income and spending. Banks loans do not create income to the borrowers account, only assets held against equally valued liabilities. The only income in the transaction are the lending fees+interest which are actually flowing in the opposite direction; from borrower to lender.

As for my own definition of money, I had to make a choice between two definitions. 1: Money as net asset value (a stock of money) and p&l (a flow of money). This is what traders and investors understand as money when they discuss concepts like risk, return and capital. And 2: money as a designation belonging to specific assets like bank deposits and not others like houses and IP. This is the definition used by macro economists and central bankers. I cannot be to blame for the fact that these different constituencies were already using incompatible definitions of money when I discovered them. My aim in using the first set of definitions is to expose this incompatibility and make it part of the discussion.

All of that said, I never meant to use these definitions in the name of MMT. I understand you are working within the system and need to speak the language of the system. If I make reference to MMT it is out of respect for the fact that I would never have understood any of this without your help.

You once said to me: “If your 401k was suddenly converted to cash does that mean you would spend it?” That was a breakthrough idea for me. The answer is no because the 401k is reserved for retirement spending and the fact that the new portfolio will not earn a positive return doesn’t change the purpose of the funds in that account. If anything it means that I now need to spend LESS than I would have otherwise in order to have the same level of retirement funds. Then I realized that I take money out of every single paycheck to put into my 401k, and so does everyone else in theory, because that’s how you are supposed to fund your retirement. Which means that every single worker is supposed to earn more than they spend. Firms are the same way; they are supposed to report profits every single quarter. So every single balance sheet in the private sector wants to earn positive net income; savings, in every period. For that to work we need someone to spend that money and that would have to be govt because there is no other entity that can run a perpetual negative balance of money. I first heard about MMT from Warren Mosler. And Bill Mitchell helped me really get it by going into so much detail as he does. But the one sentence you wrote convinced me that MMT was correct.

But if you don’t want to be associated with my crazy definitional quest for the real foundations of money, investment and trade, you don’t have to be. But I will still thank you, and cite you, because you elevated my understanding of the world.

Hi Brian

I probably shouldn’t have posted that here and should have done it privately. Sorry about that.

I love your work overall. Note that my disagreement is how you are defining what counts as “money” and what does not, not with anything you are saying about how things function, how the financial statements look, etc. Totally with you there. So, basically I’m with you 95% of the time, maybe more.

Great to hear about the one statement–flattered. Still amazes me anyone trudges through stuff I write. You totally nailed my intention there, and went even a bit further. Good stuff. And totally with you on any “quest for the real foundations of money, investment and trade.”

Best,

Scott

I left a more detailed thought for Firestone that’s under moderation. Just wanted to say I hear what you’re saying. I’m not really interested in convincing anyone I’m ‘right’. Rather, my interest is in pointing out there are other perspectives. I think this is important because economists live in an enormous bubble. Most people outside the bubble simply dismiss it without even offering a different perspective. Your explanation requires technical definitions of words which I would argue loses meaning in the aggregate.

Money is not the central part of the story. Or perhaps in less neutral, more moral language, money ought not be the central part of the story.

There are more important things than maximizing GDP. We don’t need more. We need a better distribution of what we already have.

As far as saying that government gives banks money, that’s as clear and plain-language as it gets. To add nuance to that is not to be more precise. Quite the opposite, it is to obfuscate, to justify, to make it seem like there might be some legitimate reason if only people were smart enough to get that precision. It’s the false precision of numbers, the same tactic car dealerships use in financing for lower-income buyers, giving them a precise number rather than a round number to make it seem more accurate, a better deal.

Sure, we can debate what money is. As highly paid technocrats pocket paychecks (funded by the government!) while impoverished and oppressed communities suffer the daily dehumanization and degradation of the police state. You know, those wonderful government employees. Let’s hire some more! Yay net deficit spending.

Oh what’s that, MMT wouldn’t use net deficit spending to fund the drug war? Oh, I see. So MMT doesn’t really advocate net deficit spending. Rather, it advocates certain kinds of spending.

Which is different, how, from every other approach?

The money that banks create by making loans is recognized by the government as money, and the FDIC insures deposits up to $250,000 per account to back it. So it is as good as currency.

No argument here. It is the government that makes it money.

The interesting though exercise for our banking system is to imagine what might happen if the FDIC lowered coverage to, say, $5,000. Or charred the criminal banks a non-subsidized fee for the insurance protection.

“Eh, I’d say the flaw in monetary theory today is in believing that it is a discipline distinct from political economy..”

Indeed, symptomatic of a society controlled by sociopathic/narcissistic Fat Cats where the nature of money and the uses it can be put to is not taught in schools.

It is good to see an article that spells out truth in such a simple, yet profound manner.

“The cost of money is a secondary consideration in investing. The

primary one is: will there be enough buyers for your output and will they pay you what you need to charge to make the product work?”

This may be why we are not seeing inflation: “there are not enough buyers to make the product work.”

However, “leveraged financial speculation” is the exception to this rule; thus the “booming asset prices.”

Don Levit

“will there be enough buyers for your output and will they pay you what you need to charge to make the product [worthwhile]”

These questions address the key business decision,and it is neither made nor informed by financial management. It is made by general management and chiefly informed by marketing management and those who do there market research. Financial managers and managerial accountants are just there to assist.

“Money is just a tool of power, nothing less, but nothing more, either.”

This statement assumes away the reality that a barter economy doesn’t come close to competing with a monetary economy in efficiency.

The vaunted ‘efficiency’ of the monetary economy is a matter of faith not fact. There is no such thing as a barter economy. See Graeber et al. The monetary economy is a distinct (not necessarily better or worse) way of arranging the power relations, or functions, built around the institution of money (the power to tax, the power to make money legal tender for settling debts, the juridical power inherent in the notion of ‘debt’ itself, the ability to store value over time, etc.) There are certainly alternatives to the monetary economy as it has been traditionally be represented, (see Craig Muldrew’s “The Economy of Obligation” for a good description of one in Early Modern England). But there is little reason to think they were less ‘efficient’ than the one we have today, if by efficiency we mean the adequate provision of goods and services for most people. They may, in fact, be the optimal solution for their time and place. Or not. For instance, regardless of one’s perspective it is hard to see the current arrangement of the ‘monetary economy’ as optimal for, well, almost anyone.

I heartily agree a monetized system is better than a barter system. I think the interesting question is, better at what? To what end is the greater efficiency deployed? The thing about a hammer is you can use it to build a house. Or a prison. The tool itself has no agency, no desire, no check on the wielder of the tool.

The strong dollar means eradicating any trace of inflation… that is wage-price demand inflation. So what’s so important about a strong dollar that crushes exports and eviscerates the middle class? Well…. if you are a member of the Fantasy Class which has turned everything into dollars and would be happy to eat them with ketchup if you only could, then a strong dollar means you can buy twice as much both here in this pathetic country and anywhere abroad. And USA Inc. (fat cats’ club) can buy up all the means of production. All over the world. Secret Marxists. What hypocrites.

Except for that pesky labor thing.

I like this

http://blog.mpettis.com/2014/09/not-with-a-bank-but-a-whimper/

“China’s extraordinarily high savings rate is almost wholly explained by the transfer mechanisms that subsidized rapid growth over the past two decades, leaving Chinese households with the lowest share of GDP in the world, and perhaps the lowest ever recorded for a large economy.”

The Chinese leaders decided that they needed “investment” – and they got it. Didn’t do the actual Chinese much good (I can remember in my youth a song “Take this job and shove it” – ah, the days when you could get a job…..but the truth be told, most jobs suck – ask the Chinese jumping offing building…..). Some where along the line, somebody decided we had too much equality in this country, and something had to be done about the imminent danger of everybody getting lackadaisical and mediocre, what with their secure well paying jobs. Apparently a policy of taking away jobs and money from the middle class was decided by both parties, as implemented by Goldman Sachs trained Treasury secretaries….

This is one of those things where I wonder why I spend ANY time reading, thinking, or considering economics. It really does seem to be a construct very much like religion – where someone once said something, which is than to be shown to be completely false……but there are still millions of true believers.

When I took econ 101 in college, my college textbook (this is COLLEGE….TEXTBOOK) described that money for investment came from savings (held in banks or S&Ls). Seems reasonable and logical… Much later this whole issue of “loanable funds” came up, and just a little internet research shows that it has been known for quite a while that banks create money for investment – they always did.

——————————————————————————————————————–

http://www.washingtonsblog.com/2014/03/bank-england-admits-loans-come-first-deposits-follow.html

This angle of the banking system has actually been discussed for many years by leading experts:

“The process by which banks create money is so simple that the mind is repelled.”

– Economist John Kenneth Galbraith

“[W]hen a bank makes a loan, it simply adds to the borrower’s deposit account in the bank by the amount of the loan. The money is not taken from anyone else’s deposit; it was not previously paid in to the bank by anyone. It’s new money, created by the bank for the use of the borrower.“

– Robert B. Anderson, Secretary of the Treasury under Eisenhower, in an interview reported in the August 31, 1959 issue of U.S. News and World Report

“Do private banks issue money today? Yes. Although banks no longer have the right to issue bank notes, they can create money in the form of bank deposits when they lend money to businesses, or buy securities. . . . The important thing to remember is that when banks lend money they don’t necessarily take it from anyone else to lend. Thus they ‘create’ it.”

-Congressman Wright Patman, Money Facts (House Committee on Banking and Currency, 1964)

“The modern banking system manufactures money out of nothing. The process is perhaps the most astounding piece of sleight of hand that was ever invented.”

– Sir Josiah Stamp, president of the Bank of England and the second richest man in Britain in the 1920s.

“Banks create money. That is what they are for. . . . The manufacturing process to make money consists of making an entry in a book. That is all. . . . Each and every time a Bank makes a loan . . . new Bank credit is created — brand new money.”

– Graham Towers, Governor of the Bank of Canada from 1935 to 1955.

Moreover, in First National Bank v. Daly (often referred to as the “Credit River” case) the court found that the bank created money “out of thin air”:

[The president of the First National Bank of Montgomery] admitted that all of the money or credit which was used as a consideration [for the mortgage loan given to the defendant] was created upon their books, that this was standard banking practice exercised by their bank in combination with the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneaopolis, another private bank, further that he knew of no United States statute or law that gave the Plaintiff [bank] the authority to do this.

The court also held:

The money and credit first came into existence when they [the bank] created it.

=======================================================================

So my first point is: I want a refund from my college and college textbook company for telling me something that was known to be WRONG, WRONG, WRONG for decades!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

And its not hard to explain, if only someone would try….makes me wonder if there is a conspiracy to keep it complicated?????

When you go to work…you work for free! FOR A LITTLE WHILE. Your working for the promise of your wages that you contracted for when you were hired. Than usually, after 2 weeks, you get paid. You have done real work, and you get paid in real dollars. Likewise, Banks aren’t really in the business of creating money, as so much managing contracts for the rate and duration of loans. The business that takes the loan hopefully makes a product people buy, as well as at a profit. Its doing some kind of BUSINESS that it would otherwise be unable to do without a loan.

Likewise, very high interest rates could hinder a business…but that’s not the problem now. We have had very low cost of money for years now!!! I don’t think the cost of the loans is the problem – its the lack of customers….

“You have done real work, and you get paid in real dollars”–an interesting conception of what the word “real” means today in relation to “dollars”. If accounting information created and stored in the form of temporary and transitory electronic records qualify as “real”, then you have your point.

Great piece, Phil. I think Paul Krugman’s performance illustrates his reliance on authority, rather than reason, when challenged. This has also been reflected in previous exchanges he’s had with MMT commenters and bloggers. His approach is one of denial and absolutism. he won’t really engage. He just repeats his positions, shown to be mistaken or not. See here.

Well, yes. He won a falsely so-called “Nobel” prize. When an MMTer wins one, too, then that MMTer will be worth his attention. Until then, MMT is just noise to him.

The presupposition in this comment is that authority bestowed credentials are what define “worthiness”. Which confirms JFs point that PK relies on his credentials, “rather than reason, when challenged.”

“If a person is over-committed to verbal constructs, definitions, formulae, ‘conventional wisdom’, etc., that person may be so trapped in those a priori decisions as to be unable to appropriately respond to new data from the non-verbal, not-yet-anticipated world. By definition, the extensionally oriented person, while remaining as articulate as any of her/his neighbors, is habitually open to new data, is habitually able to say, “I don’t know; let’s see.”” –From Science and Sanity by Alfred Korzybski

This was a response to MaroonBulldog.