Dave here. Interesting empirical finding, though it doesn’t take into account the nature of the credit boom, or indeed the legality of it.

By Gary Gorton, Professor of Finance, Yale School of Management, and Guillermo Ordoñez, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Pennsylvania. Cross-posted from VoxEU

Financial crises pose challenges for macroeconomists. Schularick and Taylor (2012) show that credit booms precede crises. Mendoza and Terrones (2008) claim that not all credit booms end in crises. Herrera et al. (2014) argue that crises are not necessarily the result of large negative shocks, but also of political considerations. There is a need for models displaying financial crises that are preceded by credit booms and that are not necessarily the result of large negative shocks.

In a recent paper (Gorton and Ordonez 2016), we show that credit booms are indeed not rare, that some end in crises (bad booms) but others do not (good booms). Are these two types of booms intrinsically different in their evolution, or do they just differ in how they end? We show that all credit booms start with a positive shock to productivity on average ten years before the end of the boom, but that in bad booms this increase dies off rather quickly while this is not the case for good booms. This suggests that a crisis is the result of an exhausted credit boom. We then develop a simple framework that rationalises these empirical findings and highlight several shortcomings of standard macroeconomic models that tend to neglect the interplay between macroeconomic and financial variables.

Our finding: Productivity dies off faster during bad booms

We study a sample of 34 countries (17 advanced countries and 17 emerging markets) over a 50-year time span (1960-2010). We define a credit boom as starting whenever a country experiences at least three consecutive years of positive growth in credit over GDP that averages more than 5%, and ending whenever the country experiences at least two years of no credit growth. Once we have identified credit booms, we classify them into bad (or good) depending on whether or not they are accompanied by a financial crisis (defined as in Laeven and Valencia 2012) in a neighbourhood of two years of the end of the boom. We identify 87 credit booms in our sample, 34 of which are bad booms.

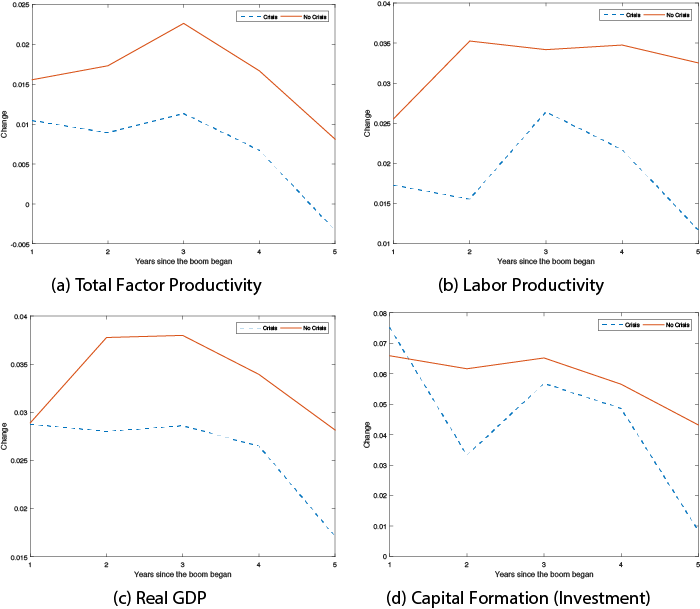

To study whether these two types of boom are fundamentally different we compare the evolution that total factor productivity and labour productivity experience. Figure 1 shows the average growth of these two productivity variables during the first five years of good booms (solid red) and bad booms (dashed blue). While on average all credit booms start with a positive shock to productivity, in bad booms this shock is smaller and tends to die off faster.

Figure 1. Average productivity over good and bad booms

We show with a regression analysis that the different patterns between good booms and bad booms that are evident in Figure 1 are both statistically and economically significant. We find that, conditional on being in a boom, an increase of one standard deviation in total factor productivity reduces the probability of being in a bad boom (a boom that will end in a crisis) by 6%. We also show that, as is consistent with previous literature, a lagged increase in credit growth predicts crises but a lagged productivity decline does not. These results suggest that the evolution of productivity at the beginnings of the credit boom that precedes a crisis is more relevant that the evolution of productivity just prior to the crisis.

Our definition of a boom is purposefully agnostic as we do not want to impose any structure on booms, since there is no theory to guide us. We prefer to let the data inform us. When we follow the standard practice of de-trending credit growth before defining the boom, we find fewer and shorter booms because most of a boom arbitrarily is pushed into the trend. A regression analysis based on this ‘more standard’ definition of booms shows no difference in productivity between good booms and bad booms, confirming that we are losing relevant information by de-trending.

While macroeconomics is plagued with models that explain financial crises as the result of large negative productivity shocks, our results suggest that crises should be studied at lower frequency than usual and that we need a comprehensive model that combines the endogenous evolution of macroeconomic variables with the generation of crises without resorting necessarily on large contemporaneous shocks.

Financial crises are not (necessarily) triggered by contemporaneous shocks

We propose a model, motivated by an earlier paper of ours (Gorton and Ordonez 2014), in which financial crises are defined by credit markets operating under a different information regime. Firms finance projects with short-term collateralised debt. Lenders can, at a cost, privately learn the quality of the collateral, but it is not always optimal to do this, in particular when the loan is financing projects that are productive and not very likely to default. If collateral is not examined for a while there is a depreciation of information about its quality such that more and more assets can be successfully used as collateral over time. This induces a credit boom in which more and more firms obtain financing and gradually adopt new projects. If there are decreasing returns such that the quality of the marginal project that is financed declines with the total level of economic activity, there is a link between the credit boom and productivity in the economy.

As credit booms evolve, the average productivity in the economy declines and lenders have more and more incentives to acquire information about the collateral backing the loan. If at some point the average productivity of the economy decays enough, there is a change of the information regime in credit markets that leads to the examination of the collateral; some firms that used to obtain loans cannot obtain them anymore and output goes down, i.e. a crisis. Immediately after the crash happens, fewer firms operate, average productivity improves and the process restarts, i.e. an endogenous credit cycle, with a series of bad booms that are not triggered by any contemporaneous fundamental shock. In our model it is the trend of productivity and not its cyclical component that determines the cyclical properties of the economy. This is in contrast with most of the standard literature on real business cycles, a low frequency theory of crises.

We also show that if the new technology keeps improving over time, as the credit boom evolves, the endogenous decline in average productivity may be compensated for by an exogenous improvement in the quality of projects such that the change of the information regime is never triggered. If this is the case, the credit boom would end, but not in a crisis, i.e. a good boom.

In our setting productivity has two components: the probability that a project succeeds, and the productivity conditional on success. While most of the macroeconomic literature implicitly assumes that firms always succeed and focuses on the second component, we explicitly differentiate between the two. We show that the first component critically affects debt markets, while the second is more relevant for equity markets. While the macroeconomic literature has focused exclusively on the later, we show the relevance of the former to understand crises.

Concluding remarks

Our empirical findings suggest that viewing aggregate fluctuations as deviations from a trend is too stark (see Lucas 1977). As far as fluctuations that involve financial crises are concerned, changes in the trend of technological change, credit booms and crises are intimately related. Financial crises are not necessarily the result of negative productivity shocks around the trend, but the trend itself determines the likelihood of crises and the cyclical properties of the economy. Cyclical dynamics originate at a lower frequency than typically understood.

‘While on average all credit booms start with a positive shock to productivity, in bad booms this shock is smaller and tends to die off faster.’

Later this is termed by the authors as an ‘agnostic’ view, yet I understand the argument made here to be that productivity drives booms of varying size, with duration of the boom determined by how well whatever innovation undertaken first attains success, and how long can it keep delivering that success until the manic energy and growth of customers for the newest version of the originally new product slowly dies in the face of waning demand.

Which booms and crashes would the authors associate with what technological advances to produce ‘good’ booms, and which ‘bad’. I sure don’t see what technology is going to deliver the sort of productivity boost it would take to galvanize investments enough to take the US economy off of its Federal Reserve money lungs.

I wonder if they authors count creating sub-prime MBS and drecky CDOs as “productivity,” because I’m pretty sure that’s what drove the last crisis.

And it apparently doesn’t take much of an increase in productivity to set off a credit boom. A change of just .01 to .015 (1-1.5%, I’m guessing, since the charts aren’t entirely clear) is apparently enough to get a boom going…sounds dubious.

Agreed. And that is not even getting to the problems with measuring productivity, which are many.

Re: small delta in productivity

The graphs they present wont help you determine the size of the productivity boom the precipitates a credit boom because the productivity boom has to be (at min) 4 years before the start of the graph (and avg is 10yr).

To tangent off your comment, though, the data here suggests that credit booms have a miniscule effect on any of the 4 economic categories they look at. At least on their definition of a credit boom. Which undermines arguments for expanding credit.

Sorry the avg is not 10yrs…i was typing in haste.

If you assume (which may not be reasonable) the graphs show the end of the boom, then the average is 6 years prior to the graph data.

Here’s one for the authors: how about do wages rise fast enough to soak up the new production and not create a realization crisis? We know in the 1920s the answer was no: wages did not keep pace with increased production and investment, and the results were bad. Credit expansion can be sustained only if wages rise as fast or faster. If they don’t, you face a crisis.

The danger isn’t just cronyism … but atrophy of Main Street. At some point, short of the Visigoths, Main Street will not be able to recover.

what about good busts and bad busts? It might not be so bad to have a bad boom if it’s followed by a good bust. that would be when you can hang out in cafes with friends, get drunk, get laid, lay around and waste time, not work too hard, if at all, and nobody around you really cares. that would be hard to model, but it’s possible maybe. evidently that’s what happened in Spain, based on my research. evidently all the youger people anyway ended up living with family and working off the books, chilling, partying, sleeping late and drinking lots of Spanish wine. Eventually that won’t work anymore, but when you’re under 35 you can keep it goingn for a long time. If you’re over 35, it’s a bust, but it may not be a bad bust if you have a hobby.

wow. it just occurred to me that a bad bust is an example of what could be called “unmonetized factor & labor productivity”. In other words, you get goods and services (like free sex and free food at home and free room and board, people looking after you, etc.) without paying money for them. that could be a way to conceptualize a “good bust”. You’d have a high degree of unmonetized factor/labor productivity. whoa! this is almost science, on a Monday morning even. It must just be luck because I’m not that smart, to think of something this compelling and erudite without working at it, frankly, very much, if at all.

IMO that is how all the best ideas arise.

typo!!!—“it just occurred to me that “a bad bust” is an example . . .”

I meant “good bust”. sorry. I meant 1 but I wrote -1. Although it’s typed correctly below.

There’s a big difference between positive infinity and negative infinity. It’s either an infinite difference or it’s twice an infinite difference. Either way, it’s a big difference. Who really cares if it’s 1 or 2 times infinity.

To my reading of this information, the quickness or speed (read: ease) in the creation of credit-financing causes the level of economic activity in the new technology to race ahead of the actual potential of the new technology to contribute to productivity improvements.

This would not be so if the level of economic activity were instead depended upon equity-financing where the incremental equity has been *earned* from the new technology by virtue of its better productivity.

To my reading, the problem is that speedy easy credit-creation chases the promise of productivity improvement via the new technology — first, it chases; then, it runs past that promise; finally, it is so far ahead that it must sit down and wait for it to catch up, which may or may not ever happen.

The authors have a ready made theoretical framework for them: use Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis. It has endo generation of financial crises resulting from usual profit seeking operations. Income-based credit growth rarely leads to crisis. Asset-based credit growth does.

What’s the point of analyzing a bust whether good or bad if one doesn’t take into account all the frauds and corruption that caused the bust? The answer for me is to not read the article because it isn’t worth reading when so much important information (i.e., fraud and corruption) is left out.

This article, and most economics, focuses too much on using money as a measure of productivity and economic activity. As pointed out in other comments, how do we measure productivity? Also we should ask, what is being produced and consummed in this credit boom? I.e. The credit boom of the late 1990’s created the technological and industrial backbone of the internet which is overall a good for society and corporations and individuals. But the boom in 2004- 2007 (2003-2014 in China), simple ‘produced’ astronomically high commodity costs, huge number of housing and construction activity backed up by shaky/stinky financial products, empty houses and buildings and huge pollution costs in China.

Furthermore from MMT, we know that the government can alter credit booms and create conditions for a gentle slowdown via regulation/enforcement and deficit spending (on real goods and financial goods in the economy provided that the debt is denominated in the local currency).

The use of debt proceeds for corporate stock buybacks, private equity LBOs, debt-funded dividend payouts, and other nonproductive purposes that benefit a relatively small group who hold the related assets or rights to them, places this most recent credit expansion firmly in the capital misallocations camp. Absent ongoing central bank cash infusions and negative real interest rates, it will eventually again become self-evident that cash flows are insufficient to service the related debt or support the borrowers’ equity prices.

Is not all saved with the expansion of the over investment in waning for the location captured market, the expansion into another unexploited market for the excess till all market options are exhausted? If the long term company histories provide lessons they point to core knitting for which there is an ensured market.

The history of the DuPonts who had gunpowder and explosives at the center of their business were assured of government purchases gif all it was was for practice explosions.

Then they went into GM, and then then left for Finance. When Finance becomes the dominate business of any nation, things go to hell.