By C.P. Chandrasekhar, Professor of Economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and Jayati Ghosh, Professor of Economics and Chairperson at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Originally published at Business Line

Many different explanations have been proffered for the “new normal” of “secular stagnation” in the global economy ever since the Great Recession. This is supposed to be exemplified by low growth, verging on stagnation, in the advanced economies, now combined with slower growth in the developing world.

Certainly the recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-09 has been anaemic at best, even as it has failed to generate much employment outside of the US (and even there it has created mostly casual, part-time and poor quality jobs). Deflation has persisted in Japan for many years now, and has become evident in the Eurozone and the US as well. Financial markets are febrile and display nervously erratic behaviour, often without proximate cause – such as in the recent collapse in bond yields across the advanced economies.

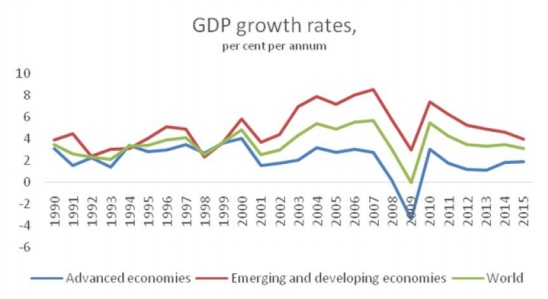

But purely in terms of GDP growth, are the last five years really so very different from past patterns of global capitalism, even compared to the supposedly more dynamic period of globalisation? Chart 1 tracks annual GDP growth in developed and developing/transition economies from 1990. The period from 2002 to 2007 does show acceleration of growth across economies, but that came to end in the collapse of 2008-09, and since then GDP growth rates have been similar to those of the 1990s.

Chart 1

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook April 2016 database

Indeed, that boom period in the 2000s could even be seen as more of an aberration. It is well known that the dynamism generated by US expansion – which in turn was driven by a finance-driven bubble centred around the US housing market – pulled the global economy into a brief period of rapid growth. This was associated with faster growth in some developing countries, particularly China, with implications for the nature and spread of economic activity.

But, precisely because it was based on a bubble, it was by definition short-lived. The inevitable collapse brought a very sharp downturn – with output declining for the advanced economies taken together, and decelerating sharply for the developing world. The “recovery” thereafter could simply be seen as a return to the more sedate growth rates that were evident in the first decade of globalisation.

But that does not mean there are no reasons for concern. First, the boom of the mid-2000s was an unsustainable bubble generated by finance, which had become the only means of generating expansion given the wage suppression and rising inequality that increasingly characterised capitalism. The realisation problem created by wage suppression – the growing difficulty of finding markets for production if mass incomes are not rising – can be answered through credit bubbles only as a very temporary solution, and one that necessarily gives rise to problems of its own. Once the bubble bursts, the need for private agents – both households and companies – to clean up their balance sheets means that deleveraging adds a further negative impetus to economic activity. So there are limits to using this as a way out of the stagnationary tendencies inherent in advanced capitalism.

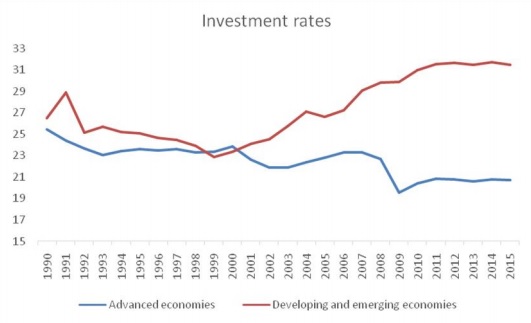

In addition, there are other ways in which the world economy is different, and why similar growth rates today cannot be seen as simply a return to status quo ante of the pre-global crisis years. Consider, for instance, the behaviour of investment rates, as shown in Chart 2. Investment rates in the advanced economies kept declining throughout the period of globalisation, even though it was supposed to provide favourable incentives for investment to private players. Various factors have contributed to this, including the emphasis since 2010 on fiscal austerity, which has reduced the positive effects that public investment could have had on private investment.

Investment rates in the developing world did indeed increase significantly in the boom years of the 2000s and have since tapered off. But it is noteworthy that they have remained high even as output has decelerated after 2010. So something is awry in the accumulation process in developing countries, which may have to do with the falling effectiveness of investment in generating more output in some larger economies like as China. So it is not only the stagnation of global demand that is a problem – which indeed it is – but the fact that relatively high rates of investment no longer serve to deliver as much output as earlier.

Chart 2

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook April 2016 database.

The other significant difference is that the global economy is now awash with supply of liquidity, because of the peculiarly one-sided response to the crisis in the developed world. Aside from the brief period just after the crisis, in 2009, expansionary fiscal policy has effectively been discarded as a possible response. Monetary policy has become not just the preferred instrument, but in most cases the only instrument, to deal with the threat of economic downturn. And this monetary policy also tends to be rather limited, focussed on “quantitative easing” and near-zero interest rates that deliver the potential to provide credit to banks but do not provide purchasing power to those who would use those resources to spend more and thus raise aggregate demand.

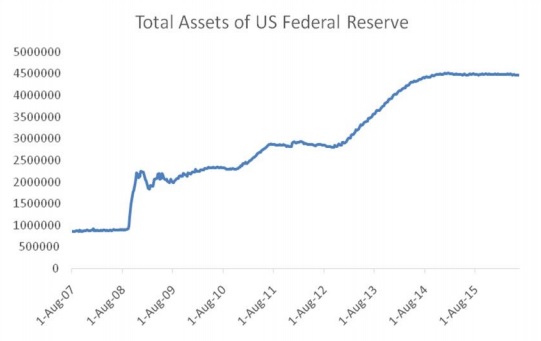

Since January 2008, total assets of the major central banks (which barely increased in the previous decade, or increased only very sluggishly) went up from around $6.5 trillion to $16.9 trillion. Excluding assets held by the People’s Bank of China (much of which are the foreign exchange reserves of the country) the assets held by all central banks went up from just under $4 trillion to nearly $12 trillion (Source: Central Bank Balance Sheets, www.yardeni.com).

The US Federal Reserve was the leader of that pack, as Chart 3 indicates. Further, after the initial post-crisis increase, the fastest and largest increase in liquidity creation by the US Fed took place in the third round of QE, between 2012 and 2014 – well after the so-called recovery was in place. The subsequent “tapering” of QE that caused so much grief to emerging markets by instigating capital flight back to the US, still left overall assets of the US Fed at unprecedented high levels.

Chart 3

But this massive injection of liquidity has only just managed to maintain some semblance of growth in the advanced economies. Meanwhile, many developing countries and emerging markets are feeling the ill effects of their own credit bubbles that they created in response to the global crisis, as credit to GDP ratios and non-performing loans have risen sharply. This adds a further depressing element to the already listless patterns of investment and consumption. Debt-fuelled expansion cannot work anymore, yet policymakers everywhere seem to think that the more sustainable and desirable option of increasing wage incomes is simply unacceptable.

It does indeed appear as if global capitalism is running out of options. This is why “the new normal” may seem a bit like the old one, but in fact is much more dangerous.

Just can’t keep inflating existing assets indefinitely. At some point, you have to both let people use them and produce new ones. But greed! It’s a conundrum.

But what happens if the world population stops growing? Or what happens if economic expansion is a direct contributor to global warming via inevitable increase in carbon emissions? Could it be that stagflation is the best way to grow out of our debt burdens? Invest accordingly.

What happens if the laws of thermodynamics* actually apply to the real world, and we discover that we can’t have unlimited growth forever? What if we will inevitably start running out of stuff? What if the win-win, non-zero sum game principles of economics are merely a form of Ponzi scheme, and we’re finally hitting true limits to growth imposed by the physical laws of the universe?

*Laws of Thermodynamics – Physicist version:

1) Matter/energy cannot be created or destroyed, only its form can be changed.

2) Entropy increases in a closed system

3) The universe is a closed system

Translation for economists:

1) You can’t win

2) You can’t break even

3) You can’t get out of the game.

Economic models that don’t take reality into account … are delusion by definition. Models without people, without actual production (financials), without banking … are prima facie malpractice.

The giant sucking sound heard round the world.

Here is an analogy. Let’s call the global economy “the patient”. In 2008 the patient was diagnosed with a malignant tumor (excessive debt). Instead of surgically removing the tumor and treating with aggressive chemotherapy and radiation, the patient’s doctors (central banks) decided to give the patient weekly blood transfusions, antibiotics, and morphine. Eight years later, the tumor has grown three times larger, the blood banks are running low, the antibiotics are no longer working, and the patient is addicted to morphine.

Sounds like a plan. They don”t need us useless eaters anymore.

I would continue to challenge the factual basis of this ongoing and misguided claim. To what end is this being repeated over and over again in our intellectual discourse? What is the purpose of such transparently inaccurate framing?

I would also continue to critique this framing. Capitalism has nothing to do with what’s been going on in our system for the past few decades. There are legitimate critiques of capitalism from our friends who are genuine leftist socialists, and I certainly encourage taking their perspectives into account.

However, the actual problems we confront today are not due to market-based economics. Rather, they are due to public policy choices that are not consistent with market-based economics. To define the national security state and the domestic police state and financial fraud and bank bailouts and tax loopholes and corporate welfare and corporate trade pacts and media consolidation and expansive IP law and so forth as capitalism is to so mangle the word that it ceases to have any useful meaning in describing various approaches to organizing political economy in the era of the nation-state.

You rant looks like the “no true Scotsman” fallacy to me.

I would counter that your dismissiveness looks like an effort to ignore the issues to me. You may not be self-aware of this, but you’re expressing one of the common methods that the status quo has used to deflect criticism. Instead of responding to the substance, throw out some nebulous, inapplicable charge and hope it diverts attention.

w, I agree with you, what the New Deal did was put capitalism into a framework where it was required to distribute half the benefits of the system.

Reagan/Thatcher set about dismantling that framework. By the end of Clinton’s second term this liberated capitalism had created a new oligarchy that seized power in 2000 and set about dismantling capitalism.

Continued capitalism at that point would have subjected the oligarchy to competition, but it was rich/powerful enough to buy the politics necessary to rid the Western system of capitalism.

Obama was elected to reverse this reality but signed on to riches instead. We haven’t had capitalism in at least a decade.

Capitalism has been hijacked?

Oh, if only the Czar knew!

The process you refer to, jsn, is intrinsic to capitalism and political economy. It’s only by falsely positing (an academic, abstract) split between politics/power and economy that the “this is not REAL capitalism” meme can continue.

It is the very nature of capitalism to monopolise, to distort markets and to dominate the political process.

Certainly “late stage capitalism” can be highly correlated with the idea that free markets always provide “right” answers. A doctrine pursued with a degree of fervency and attention to orthodoxy that makes it appear that they are a source of morality, indeed that free markets are religion in their own right. Markets are a great tool aggregate personal choices into production decisions. But when we decide that the answers that free markets provide are immoral (poor people get no medical care) we are NOT forced by the invisible hand to obey them.

What you are describing is capitalism. That is a plain English definition of a phrase called market failure.

But moreover, my point is about the things government does do that are authoritarian, not the things it doesn’t do (for which, healthcare is actually not a good example, since every industrialized government spends lots of money on healthcare, from the US to the UK to Germany). The massive wage inequality between home health aides and the doctors and other administrators running hospital chains, for example, is not due to ‘markets’. It exists because of public policy choices that allocate resources in that way.

And the public policy choices are made by politicians and bureaucrats put in power by…the “markets”, i.e., by capitalists.

Last I checked, the USA is completely politically dominated by two capitalist political organizations. Its mass media completely consists of commercial capitalist corporations, with PBS dominated by the “nonprofit” foundation arm of the same capitalists. Capitalism consists not merely of economics, but also politics. Politics of a historically determinate type, just like the economics. Politics and economics don’t live in separate universes. The live in the same social world.

Looks like the perfect “political marketplace” + “marketplace of ideas”. Yet it somehow produces “bad” policy.

But here is what is actually going on: Capitalism’s own determinate rationality produces bad economics. At the same time, in parallel and not as simple consequence, capitalist politics produces bad policy. Bad, not for capital, but for US.

If you’re speaking of some textbook definition you might be correct. However, the real-world version looks pretty much exactly like what’s been going on not only for the last few decades but what goes on when ever the owners of capital manage to leverage their wealth to control the political system to their advantage. Which is to say, pretty much forever.

Agreed, that’s why capitalism is a poor word choice. The public policy that is actually happening in the real world has no meaningful connection to the ideas of market-based economics.

(That doesn’t necessarily make the ideas of capitalism a solution. It simply means that those ideas aren’t the problem. The most important step in problem solving is understanding the problem, and that’s why our intellectual discourse has become so tied up in knots to scapegoat capitalism. It helps prevent analysis of the actual problem.)

My issue with your formulation is the whole idea of “markets”, which is a reified way of saying “people making choices”. Everything you describe, all the bad policies, are people making choices. No one held a gun to anyone’s head (at least not in the advanced capitalist world–Chinese and Indian peasants, perhaps). We and our elected officials, our judges and our economists, made choices. We wanted to believe that getting rich was wonderful, that “efficiency’ was much more important than compassion, and that success was more important than justice or fairness.

The only way markets can function in the way you seem to posit them operating (in contradistinction from the way they do today) is if everyone went into them with exactly the same amount of knowledge and the same amount of money and faced on the other side a bewildering variety of producers and service providers bidding honestly and individually for our dollars. And I don’t see where that has, or could, exist.

I’m glad this thread generated good discussion.

However, I think we’re not really directly addressing each other. If I can speak broadly as well as answering your particular point, what I find interesting about this discussion is that people are by and large wanting an easy scapegoat to blame rather than actually analyzing the situation. The logical conclusion of saying that ideas lead to our present system is to say that all such foundational ideas, therefore, have failed.

For example, you talk about efficiency, but your premise is fundamentally flawed. Our public policy choices today are not generally based upon seeking efficiency. Or for another example, you talk about theoretical knowledge in markets, yet the real world policy areas I mentioned aren’t markets. We run the largest prison system on the planet. We run the most inefficient healthcare system on the planet. On and on, our present system is characterized neither by efficiency nor by markets. The way the drug “market” works today is that an armed government agent kidnaps you, or steals your cash, or your car, or your bank account, or all of the above. The descriptive value of the term market in that arrangement is essentially zero.

It’s not just capitalism that is the problem in this mindset. Democracy, individual rights, rule of law, the Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution. The logical conclusion, since those kinds of ideas have been used to create our current system, is to replace the Constitutional view of government with moar authoritarianism. We need to create a system that is moar powerful, moar bigger, than any possible arrangement of private sector actors.

This creates, ironically, an intellectual defense of the status quo, not a rejection thereof, because our existing system doesn’t actually base public policy on the ideas supposedly being rejected.

Who cares what its called. This system blows, time for something new. The poor & working class deserve their break. Wtf?

Crony capitalism… there, fixed it for ya!

“A so-called self-regulating market economy may evolve into Mafia capitalism – and a Mafia political system – a concern that has unfortunately become all too real in some parts of the world.” Karl Polanyi

++

Capitalism is unstable – it always evolves toward wealth inequality – as anyone who has played Monopoly knows. As wealth inequality grows, greed and fraud are rewarded since laws and policies are controlled by those who gain from wealth inequality – the 1% who rig the game. This accelerates the polarization of wealth. Rather than Polanyi’s “may evolve”, I tend to think it “always evolves” into mafia capitalism – plenty of historical examples. The only issue is the time scale before the eventual backlash — generally determined by when some 1%ers cut a deal with the masses to reform capitalism — masses who are later sold out by those same leaders and the rules are once again changed, accelerating the instability. But even without the rule changes, even without the transformation to the mafia capitalism, the instability in capitalism is still there – as in Monopoly.

Business opportunity: New versions of two learning-tool games, Monopoly and Risk! For the former, winner gets to watch the other players just die, while the board, hotels and all, slowly heats and turns to ash. For Risk!, first player to take over half the world causes micro-nuclear weapon to detonate under game board.

If we could just get the right players at the table!!

Has nothing to do with capitalism? Many would say it is the very heart of capitalism. Keeping costs down by suppressing wages has been standard policy at companies of every size for decades. And it seems entirely reasonable to see that same wage suppression as the primary cause of the growth of inequality.

Capitalism can not fail, it can only be failed.

Dogma is breathtaking.

What do Noam Chomsky, the mainstream cliometricians Peter H. Lindert, Jeffrey G. Williamson (Unequal Gains: American Growth and Inequality since 1700, 2016), and the above post have in common?

They all adamantly reject the concept that the capitalist system can be described by “laws of motion” (to use the Newtonian metaphor) historically specific to itself, independently of state policy. That’s what the statement, “Capitalism has nothing to do with what’s been going on in our system for the past few decades….However, the actual problems we confront today are not due to market-based economics. Rather, they are due to public policy choices that are not consistent with market-based economics”, means.

It is of course classic libertarian dogma. However, it is the scientific *moral* equivalent of the Roman Church’s denial of Galileo’s critique of the Ptolemaic theory of the solar system. “Market-based economics” is the analogue of the immovable Earth at the center of the universe; “policy” is that Sun required to move correctly around the Earth according to the dogma.

And thanks to Newton, now we know that not only is the Earth in orbit around the Sun, but that all matter is in motion defined in large part by the *determinate laws* of an invisible force: gravity.

And if you say that the analogy with physics doesn’t hold because “market economics” is an aspect of human sociability, well then all this socialist can say is: “Gotcha”.

Because you can’t have it both ways, libertarians. Your “market economics” stands either within or without human society. If within, then you must admit that the social scientist can make an investigation into the nature of its human, social, relationships.

Or, like the Pope, or like many libertarians, you can hate the very idea of social science and demand recantation. Either way, “Eppur si muove!”.

But if this is the case, then there IS no capitalism. (and never was) Because what you describe is “actually existing capitalism.”

“is to so mangle the word that it ceases to have any useful meaning in describing various approaches to organizing political economy in the era of the nation-state.”

The word is mostly useless but we lack better, at times I just say the existing economic system – nuff said. Capitalism is not a bad term as it indicates to WHOSE benefit the system IS run. But if some people are off defining capitalism as not having much state influence in the economic system (libertarians sometimes but this is also what Dem partisans – an even more foolish bunch by far – believe). Then well hmm, that doesn’t very accurately describe the situation. And if some people are off defining capitalism as anything with markets, then that’s way too broad to be useful either.

So if I say I’m anti-capitalist, it means mostly I think we can do better than capitalist ownership of the means of production (and of course than capitalist ownership of the political system). Anti-capitalist is enough of a political position but it depends on people understanding that capitalism here means capitalist ownership of the means of production.

People are reading intent into your post (“oh must be a libertarian!”) but I just read semantic confusion. And since words have no absolute fixed meaning but are dependent on social use (see how many foolish comments there are on your post by those treating words, not actual systems in the real world but words, as having fixed meanings) … And since that particular term “capitalism” has been so endlessly muddled (so that it DOES NOT EVEN have a consensus meaning), it’s all innocent enough. It’s true that the consensus meaning differs depending on whether you travel in libertarian or Marxist or Democrat circles but so what? When a term itself builds walls that make communication impossible with no way but to talk past people, it’s pretty useless, but we lack better.

One could argue those GDP growth numbers have a built in upside bias. That’s before you even account for loss of natural resources and public health.

http://www.shadowstats.com/alternate_data/gross-domestic-product-charts

What, no mention of the One True Organizing Principle, neoliberalism/neoconservatism? Seems to me “capitalism” as a thing is a nice debate frame, but useless as any kind of analytical category for anyone trying to figure out how to keep the fokking species alive and halt and reverse the damage we naked apes are growing our way into.

Too bad there apparently ain’t any countervailing Organizing Principle (that stands a prayer of general adoption ( in the face of the insatiable lusts of our limbic systems) that might lead to Commensalism over MORE!ism…

Without PRICE discovery there is no longer market based true capitalism.

CRONY capitalism is what describes what has gone wrong, since CBers decided to ‘manage’ the Economy and monetary policies, especially after 2008!

And does PRICE, for the Friedmaniac True Believers, apologists and fellow scammers, include ALL EXTERNALITIES? If so, how?

And how does PRICE account for stuff like consumer momentum, like people who grok the packaging without noticing the fine print, who pick up 59 ounces of orange juice thinking they are getting the usual “half gallon size class” for the 64-ounce “half-gallon” price, because they always have bought that size class before? Where the retailer and the rest of the supply chain scam the “increment profit” from the barely legible product quantity label indicating to only the observant that a 64-ounce “half gallon” is now actually about 8% smaller?

Oh, I know, it’s all “a fool and his or her money is soon parted,” and ” there’s a sucker born every minute.” Yah, perfect price discovery, all right… And I’m not knocking Sunny’s comment at all, just spitting out some cynical (“disappointed romantic”) bile…

A new set of ideas came in with Thatcher and Reagan in the 1980s and for a while they seemed to work, eight years after 2008, it is time to start thinking of some new ideas.

Did we call the “Great Depression” of the 1930s the “New Normal” and just accept it?

Did we call the stagflation and stagnation of the 1970s the “New Normal” and just accept it?

At each stage we recognised that version of Capitalism had failed and bought in new ideas to get things going again.

The prospects for this version of Capitalism were never good, neoclassical economic ideas culminated in the Wall Street crash of 1929 and everything went downhill until the ideas of the “New Deal” came in.

These ideas worked very well for the Golden Age of the 1950s and 1960s.

Neoclassical economics has ended up in another Wall Street Crash in 2008 with the global economy stagnating since 2008.

It’s time for new ideas or some rehashed old ideas to tide us over for a while.

Even the rehashed neoclassical economics worked for a decade or two.

As demand is today’s problem, rehashed Keynesian ideas could be just what we are looking for with twenty years to work out what went wrong in the 1970s or develop new ideas.

aggregate production necessarily creates an equal quantity of aggregate demand (Say’s law)

Fordism is “the eponymous manufacturing system designed to spew out standardized, low-cost goods and afford its workers decent enough wages to buy them”.

“A business that makes nothing but money is a poor business.” Henry Ford