Lambert here: I’m with Yves, who views “the emphasis in the US on ‘happiness’.. as an illusory goal. Happiness American style is giddiness or euphoria and is by nature a fleeting state. Contentment is more durable and more attainable….” I’m also with Freud, who wrote that “you will see for yourself that much has been gained if we succeed in turning your hysterical misery into common unhappiness.” I think we could all do with a little less hysterical misery just about now, eh?

By Andrew Clark, CNRS Research Professor at Paris School of Economics (PSE), Sarah Fleche, Researcher, Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics, Richard Layard, Founder and Emeritus Professor, Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics, Nattavudh Powdthavee, Professor of Behavioural Science, Warwick Business School, and George Ward, Researcher at the Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics. Originally published at VoxEU.

Understanding the key determinants of people’s life satisfaction will suggest policies for how best to reduce misery and promote wellbeing. This column discusses evidence from survey data on Australia, Britain, Germany, and the US which indicate that the things that matter most are people’s social relationships and their mental and physical health; and that the best predictor of an adult’s life satisfaction is their emotional health as a child. The authors call for a new focus for public policy: not ‘wealth creation’ but ‘wellbeing creation’.

In 1961, the OECD organised a conference on human capital that propelled education into the centre of policy-making worldwide (OECD 1962, Schultz 1961). This month, the OECD and the London School of Economics (LSE) are holding a conference on subjective wellbeing that they hope will usher in another revolution – where policymaking at last aims at what really matters: the happiness of the people.

As Thomas Jefferson once said, “The care of human life and happiness… is the only legitimate object of good government”. But to make policy requires numbers. Human capital took off once people realised its high rate of return. Wellbeing will only take off when policymakers have numbers that tell them how any change of policy will affect the measured wellbeing of the people, and at what cost.

Key Determinants of Wellbeing

The first step is a clear unified account of how wellbeing is currently determined. Our book, the first draft of which will be presented as the conference, aims to provide this, using large surveys from four major advanced countries (Clark et al, forthcoming).

One key issue is to adopt a single definition of wellbeing. The right definition, in our view, should be life satisfaction: “Overall how satisfied are you with your life, these days?”, measured on a scale of 0 to 10 (from “extremely dissatisfied” to “extremely satisfied”). That is a profoundly democratic concept because it allows people to evaluate their own wellbeing rather than have policymakers deciding what is more important for them and what is less so.

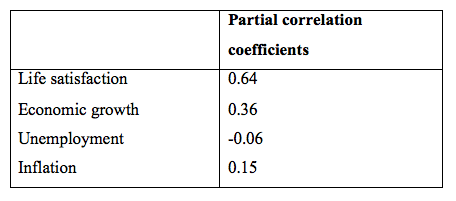

Moreover, policymakers like the concept – and so they should. Work in our group at LSE shows that in European elections since 1970 the life satisfaction of the people is the best predictor of whether the government gets re-elected – much more important than economic growth, unemployment or inflation (see Table 1).

Table 1. Factors explaining existing government’s vote share

Notes: Eurobarometer data on life satisfaction and standard election data for most European countries since the 1970s.

Source: Ward (2015).

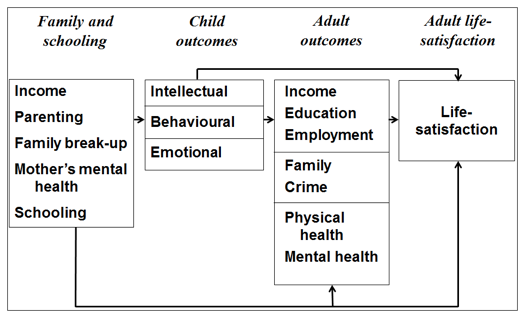

So the task is to explain how all the different factors affect our life satisfaction, entering them all simultaneously in the same equation. There are of course immediate influences (our current situation) but also more distant ones going back to our childhood, schooling and family background. Figure 1 gives a stylised version of how our life satisfaction as an adult is determined.

Figure 1. Determinants of adult life satisfaction

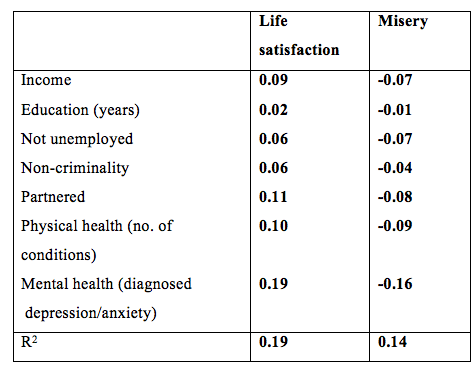

We can start with the immediate causes, as shown in Table 2. The first column measures how far different factors can explain the wide dispersion of life satisfaction in the population. As can be seen, the big factors are all non-economic (whether someone is partnered, and especially how healthy they are). The partial correlation coefficient on income is 0.09, which means that less than 1% of the variance of life satisfaction is explained by income inequality.

Table 2. Explaining the variation of life satisfaction and of misery among adults

(partial correlation coefficients)

Notes: Data mostly from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), using pooled cross-sections. The non-criminality result comes from the British Cohort Study using arrest data up to age 34. The mental health result comes from cross-sectional analysis of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) and the US Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), which both give very similar results.

An obvious question is: do economic factors play a bigger role if we focus only on those who are least happy (the bottom 10% of the population in terms of life satisfaction)? We investigate this in the second column of Table 2, which explains whether somebody has as little life satisfaction as the lowest 10% of the population. The results are almost the same as before.

The Misery Caused by Mental Illness

When we ask what distinguishes Les Misérables from the rest, the biggest distinguishing feature (other things equal) is neither poverty nor unemployment but mental illness. And it explains more of the misery in the community than physical illness does.

Watch Richard Layard explain why treating mental illnesses should be on the public agenda in the video below

In fact, it is interesting to ask: “If we wanted to reduce the numbers in misery, what change would have the biggest effect?” This is addressed in Table 3 – if we could abolish depression and anxiety, it would reduce misery by as much as if we could abolish all of poverty, unemployment and the worst physical illness.

Table 3. What would most reduce the percentage of people in misery (ceteris paribus)?

Notes: Data mostly from the BHPS except for depression. Total in misery is 10 percentage points.

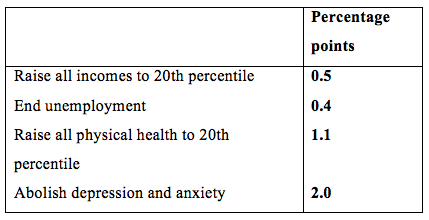

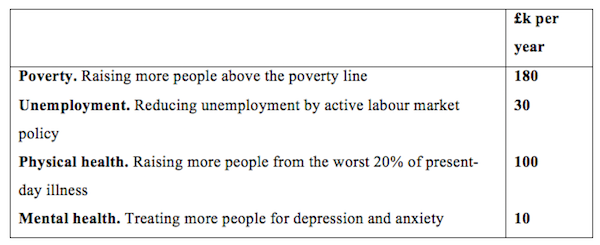

Except for poverty, we cannot of course completely abolish any of these things, but we can reduce them all at the margin – and at a cost. So Table 4 estimates very roughly the average cost of reducing the numbers in misery by one person, through different policies.

Table 4. Average cost of reducing the numbers in poverty, by one person

As Table 4 shows, it costs money to reduce misery, but the cheapest of the four policies is treating depression and anxiety disorders. This is why the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE has been involved in two major mental health initiatives.

Since 2008, Britain’s National Health Service has developed a nationwide service with different local names but known generically as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT). This programme now treats over half a million people with depression or anxiety disorders annually, of whom 50% recover during treatment. Because of financial flowbacks, we believe it in fact costs the government nothing, so that the cost shown in Table 4 is an exaggeration (Layard and Clark 2014).

In addition, we should try to prevent mental illness before it occurs, so a second initiative is preventive – a four-year curriculum called Healthy Minds, one lesson a week. This too has very low costs since children are already spending an hour a week on life skills lessons of unknown, but probably, low effectiveness.

Children’S Development and Adult Life Satisfaction

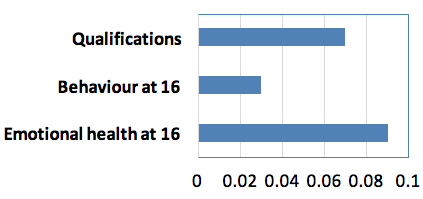

The importance of prevention becomes even more evident if we revert to the life course diagram with which we started and try to predict adult life satisfaction from earlier in a person’s life, from their child development – their academic qualifications, their behaviour at 16 and their emotional health at 16. Figure 2 shows the relevant partial correlation coefficients.

The best predictor of an adult’s life satisfaction is their emotional health as a child. How on earth did so many policymakers come to believe that qualifications were the be-all and end-all – ‘in the interests of the child’?

Figure 2. How adults’ life satisfaction is affected by different aspects of their development as children (partial correlation coefficients)

Notes: British Cohort Study data. Intellectual performance is highest qualification. Behaviour at 16 as reported by the mother and emotional health at 16 as reported by mother and child.

What Influences Children’s Emotional Health

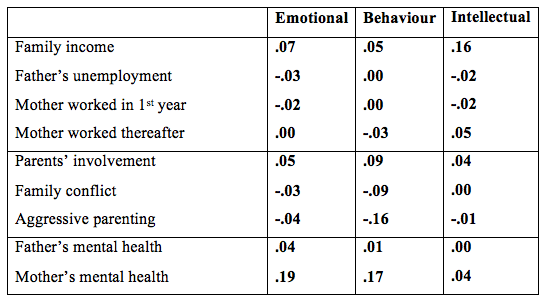

The final step in our book is the explanation of these child outcomes, using data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), which has surveyed children born in and around the city of Bristol in 1991/92. This is shown in Table 5.

Academic performance is the outcome on which most existing research has focused, and it is profoundly affected by family income. But the emotional health of the child is the best measure of the wellbeing of the child, and it is also (as we have seen) the biggest determinant of the wellbeing of the future adult. It is affected to some extent also by family income but above all by the mother’s mental health. The same is true of the child’s behaviour – which also affects the wellbeing of so many other people.

Table 5. How child outcomes at 5, 11 and 16 (averaged) are affected by different factors

(ALSPAC data, partial correlation coefficients)

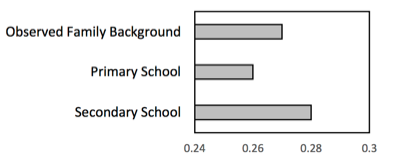

What about the effect of schools? In the 1960s, the Coleman Report in the US told us that parents mattered more than schools. Since then the tide of opinion has turned. Our data strongly confirm the importance of the individual school and the individual teacher. This applies equally to the academic performance of the pupils and to their happiness.

So in Figure 3, we look at the emotional wellbeing of children at 16 and show how it is explained. The top bar shows the combined effect of all observed family factors (treated as a single weighted variable). The next bar shows the enduring effect of the primary school a child went to (again a single aggregate of dummy variables) and the last is the effect of secondary schools. Schools really matter.

Figure 3. How child emotional wellbeing at 16 is affected by family and schooling (ALSPAC data)

Source: Flèche (2016).

Income and Happiness

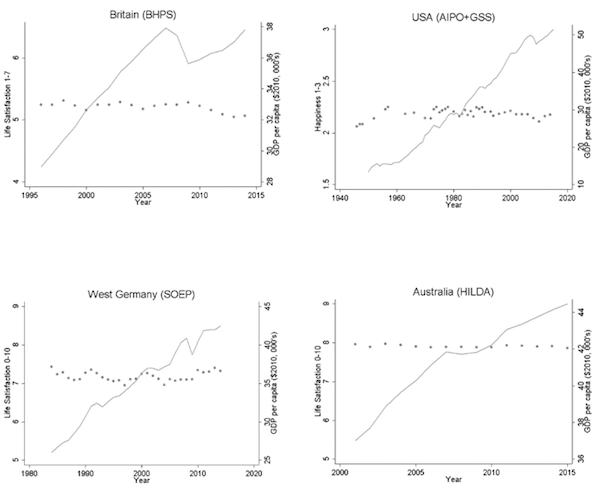

Let us end with the thorny question of income. As we have seen, income inequality explains a very small fraction (under 2% in any country) of the variance of life satisfaction. But the effect of log income is well determined, and similar in all countries. One would therefore have expected economic growth to bring considerable increases in life satisfaction. But in many countries, it has not – the so-called ‘Easterlin paradox’ (Easterlin 1974). This is illustrated for our four countries in Figure 4.

Our analysis provides an explanation of this. People adapt to higher levels of income over time, but much more importantly, they also compare their own income to that of their peers. Using the BHPS, we find that life satisfaction (0-10) is predicted mainly by an individual’s income relative to that of others in their peer group as defined by age, gender and region. The same is true in Australia and Germany.

Figure 4. Average income and wellbeing over time

Notes: Data from Britain/BHPS; Germany/Socio-economic Panel (SOEP); Australia/HILDA; US/General Social Survey.

Happiness and Policy Analysis

At last the map of happiness is becoming clearer and usable for policy analysis. We now need thousands of well-controlled trials of specific policies from which we can obtain estimates of the effects on life satisfaction in the near and longer term (where our book can contribute valuable coefficients). We can then compare those gains to the net cost of the policies. The optimal mix will surely be very different from the one we have now.

Authors’ note: We are extremely grateful to all survey organisations, their staff and their respondents for access to their data. The Conference on 12-13 December 2016 is jointly organised by the OECD, the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE and the CEPREMAP Wellbeing Observatory of the Paris School of Economics, in conjunction with the What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

I liked some of the conclusions which were fine, as far as they went. But they just don’t apply to me on some emotional level, even though, logically I accept the vast majority of the analysis and the underlying methodology.

What are you on about, Clive, I can hear people muttering (maybe there’s too much unhappiness in their lives)… so how to explain.

The best that I can come up with is by way of an example. The thing that caused me the most disquiet — I’d stop short of calling it being miserable but it has been profoundly unsettling — I recently have been left a small inheritance. Nothing massive, as in fundamentally life-changing (the negative effects of sudden highly disruptive increases in personal wealth such as through lottery wins are well documented) just £45,000 now and possibly another £10-15,000 in another few months as the estate is completely realised.

But this comes as but the latest in a series of such bequests (it is the largest, but there have been two others on smaller scales in th past 20 years). And it raises so many ill feelings and shifting malaise. Things such as, why am I then still working in an exploitative industry in a preposterous role that is little more than day-care for adults and comprised mostly of meaningless busywork. Or, why do I keep benefiting from capricious good luck while so many others get the exact opposite. Worst by far is, if I am determined to leave this world a better place when I finally shrug off this mortal coil, why aren’t I doing more about it — it is not financial constraints — but what more can I do (and won’t it be any less futile that anyone else’s efforts, I don’t kid myself, I’m not that special and not that gifted an certainly not that well connected enough to achieve anything dramatic or out of the ordinary).

In short, the more I have, the more miserable I am and the more conflicted I become about what to do about it. On everything in the above-mentioned feature’s criteria, I tick all the right boxes for happiness or, even, and I prefer this as a concept, as Lambert described it, contentment.

So either the author is wrong or I am.

(yes, and I do appreciate this needs the hastag of FirstWorldProblems or AreYouWhiningForEngland so apologies for the self indulgent kvetching, hopefully readers will understand what I am trying to get at here)

In short, the more I have, the more miserable I am Clive

Been there a couple of times though I’ve never had enough to be economically secure. Now that I’m retired I am economically secure, at least for a while*, but even that security feels insecure in itself.

I suggest you read Proverbs; it has a lot to say about wisdom, money, contentment, etc.

And thanks for your candor.

*I live off Social Security and a tiny annuity. Politicians threaten the first and the Federal Reserve the second, I imagine.

I recently went through those emotions related to an inheritance. Getting money through that route does bring up a lot of feelings, I think, because it skips over the labor economy and goes back to an older relationship than the market relationship: the blood tie.

The people who I inherited the money from, my grandparents, died within a year of one another after sixty some years of marriage. They were sweet people. I never heard a bad word from my grandmother, never any backbiting. My grandfather was a G Man and had a nice long retirement where he got to enjoy life.

It ends up being a value placed on a life. “My (uncle, grandma, father, brother) was worth $X and now I get $X-Y because they are dead.” They worked for so many years and this is what they have to show for it. It’s kind of pathetic. And it’s so based on the vagaries of the markets, the ups and downs of 401(craps) or if they were lucky to get a pension or not. I had an elderly family member who invested heavily in Merril Lynch in 2005. Ouch.

The way I see it is that if you’re happy about an inheritance, you’re probably an asshole. But I’ve met people who bitched about being in a last will and testament and those are people I try to avoid, because I don’t trust them.

It (inheritances) does bring out the worst in people. A lifetime ago, I used to work at the sharp end of retail banking and one of my tasks was to field enquiries about incoming wire transfers (had this- or that- been received, what is the amount etc.)

Usually these were routine, mainly commercial customers checking they’d been paid or people completing on a property purchase, making sure they could hand the keys over, that sot of thing. But once in a while, you’d get either an individual or, worse a gaggle or people on a party line asking about an incoming payment from an estate. I soon learned to identify this group. Some were obviously in pretty straightened circumstances and you could tell from what they said it was a lifeline for them. That was an eye-opener in itself, sometimes a fairly trivial amount — maybe £5,000 or £10,000 was, shocking, enough to transform them from abject despair into, if not out-and-out happiness, at least a facsimile of it. That lot, I could forgive.

The most objectionable though were those who you could tell by looking at the recipient account were not poverty stricken but were grasping at every penny dear old gramps had sent their way when he croaked.

Sometimes you’d get embroiled in a generation-long family feud (at least by proxy) because, when I read the amount back to them of the wire payment, it was clearly way short of what they’d been anticipating. The news that blessed granny had, while they were alive, successfully bought the good wishes of these fickle relatives by saying “oh, of course, when I’m gone, I’ll leave equal shares of (insert here property, an investment portfolio, some other asset) to you all” but either knowingly or, sometimes, unavoidably, had to draw down capital and use as income as life went on and then — again, either intentionally or by accidental omission — misled those relatives showed the very worst side of people.

It taught me (along with other examples) that the pursuit of money only makes people miserable. Even having it doesn’t make one happy. And often, the more money they had, the more miserable they become.

Which is contrary to the findings in the above research, although, as reading the whole piece shows, it is more complicated than that.

I get you, the science in this article does reflect a certain “If X condition, then Y happiness”, but as your post also shows, things are more complicated than that.

Granny reports needing only a certain income in order to be happy and then passes that info along to her grandkids to show them what the inheritance will be, when actually she needs more than she thinks she does to remain content. Later, that imbalance comes due.

Plenty of people report that the most fulfilling times of their lives were also hard times. Sometimes the best art is produced under some duress and without recognition. Social science hasn’t caught up to the humanities in that regard.

Good luck and stay mindful! I will try as well.

I stopped reading this article at the end of the fourth paragraph. Four developed country…the survey….God! So many surveys all around and since a hundred years and finally this bizarre talk of well-being and happiness! Yes, I write this from the Developing World and would like to contend that the very attempt at conversation about Happiness nullifies the chance of getting it. Very talk of well-being makes me yawn like being in an Yoga class listening to a Fat guru.

Sorry for deviating from the thoughts in this thread — I really liked your image of “being in an Yoga class listening to a Fat guru.”

Hemang, You don’t sound very happy. Lol.

It’s an old story, this grasping after Happiness:

This is a problem which wealthy families have faced for centuries. Jarndyce v Jarndyce, the chancery court case referred to by Charles Dickens throughout his book Bleak House, is about a family fighting over the fortune of a deceased. Miss Flite had long since lost her mind when the narrative begins. Richard Carstone dies trying to win the inheritance for himself after spending much of his life so distracted by the notion of it that he cannot commit to any other pursuit. John Jarndyce, by contrast, finds the whole process tiresome and tries to have as little to do with it as he possibly can. The court case goes on interminably and finally ends up with the entire estate devoured in legal fees so there is nothing further to fight over!

Sadly the case of Jarndyce v Jarndyce has not given succession and estate lawyers a good name. Many UHNW families are suspicious of professionals putting in place structures and plans which in due course feather their own nest rather than that of the family. https://familybhive.com/article/524c2193a8b38/Jarndyce-v-Jarndyce-a-modern-day-Bleak-House

I got a friend whose aunt was one of the wealthiest people in FL when she died recently. Her children and other family members are in full trial-by-combat over the

carcass“estate.” He was hoping for some small remembrance, but seems content that he’s not involved.And some recent attention here was given to a certain Scandinavian concept that has been hijacked for monetization and commercialization, “Lagom:” very roughly, enough but not too much. http://livingenough.com/2014/12/scandinavian-wisdom/ Too bad that for the people that end up being the most greedy and perverse, the skill sets for looting seem to be concentrated in their set of DNA…

Far as I’m concerned, the article posted is unmitigated pseudo-“social-scientific” BS. And you have to love the arrogance of these people, offering that stuff as any kind of framework for “policy,” that other fraud… Talcott Parsons shot a lot closer to the mark: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structural_functionalism But it’s prretty clear the parts of the society do NOT “work together to promote solidarity and stability.” Hippie thinking…

In all seriousness, try mushrooms. The first time I took them it was a very small dose–and it quickly let me see just how ridiculous and worthless all the myriad artificial social constructs in our lives are. It’s like seeing the world for the first time with all social programming you’ve been receiving since infancy suddenly vanished, and it’s a feeling/knowledge that can permanently stay with you ever after. It won’t work for everyone, but definitely worth a try!

Also, if there are any nasty people in your life egging you on to work harder or live a certain way walk out on them immediately–no questions asked, no warning. It can really work! Just my personal recipe for happiness. Your mileage may very.

And the mushrooms let you see how very beautiful the world is. They also open your feelings to receive the beauty. The experience is transforming.

Writing in the Middle of the 19th century, Soren Kierkegaard pointed out that people had been infected with an “unnatural world-historical consciousness” that simultaneously made them hyper-aware of abstract problems like “world hunger” — which they could do nothing about — and blinded them to practical problems right in front of them, like a specific hungry person — which they could. This is much more the case now than it was in 1856.

You think that 50,000 quid isn’t enough to make an appreciable difference in the world? You think your little inheritances, your little instances of undeserved good fortune can’t make the world a profoundly better place? You are wrong. While that amount is not a big deal to you, it would be to many, many others. So here’s what I suggest you do: find someone who is struggling and give them ALL of the inheritance. Do this anonymously if at all possible. Or find a couple of people who need a hand and divvy it up into two or three good-sized chunks.

If you do this, you will find that what you think is an insignificant sum is, in fact, a massive amount, capable of doing more good than you can imagine. There is no objective world, only the individual subjective worlds that each of us inhabits. For someone who is just barely scraping by, always worrying about money, never having any kind of cushion, a five-figure windfall is nothing less than a miracle from on-high. You have the opportunity to create such a miracle. As an added benefit, you will no longer need to be saddened by your good fortune, as you will have passed it off to someone else who is in a better situation to appreciate it. Win-win.

Think of it as an experiment and report back to us what your findings are. I’ll be waiting :-)

That’s an interesting one. I have given over £25,000, conservatively, over the last 5 years to “good causes”. It wasn’t a single sum to a single body or individual but I am discerning and don’t adopt a scattershot approach so I doubt it’s more than 5 or 6 in total. While I have been gratified by some, I’ve been truly appalled by the outcomes in others.

One disability support charity provided services to people which were a statutory responsibility of the government. The fact that the state did not adhere to its responsibility definitely led to disabled people suffering, but it was not at all happy that the funds I had donated were being used to let the state off the hook in this way. Providing legal advice to the people impacted to challenge the wrongdoing would have been fine but I was severely let down by the enabling which the charity ended up doing.

Another animal welfare charity which I gave a substantial grant to give shelter and veterinary treatment to abandoned animals and, at least initially, concentrated on those which would be difficult to find suitable places to look after them, let alone any rehoming. I was interested in the charity because it combined alternative therapies alongside conventional treatment. But as time went on, the lead individual in the organization became more and more dismissive of conventional veterinary approachs and kept animals alive where they not only seemed to suffer greatly but also compounded the issue by “rescuing” more animals than could realistically be helped given the inevitable fiscal constraints. That such a situation could come about as a result of my well-intentioned actions was nearly heartbreaking.

So I’m not entirely convinced that such an action as you suggest would inevitably increase the sum total of human happiness. And there’s a distinct possibility it could do the exact opposite.

To take but one of many possible examples: I’m working with a collective right now starting up a sustainable business. Two of my comadres in the project are a couple of women in their late 50s. One is on medical disability of $750/mo, which she manages to live on, somehow. She’s a tireless volunteer and a very intelligent woman, but has never had the breaks that some of us have, and so is in an all too common situation. The other works as an independent housekeeper, getting gigs cleaning offices around town at night. She ran a “women’s music” (code for lesbian music) label back in the ’80s for quite awhile, but is now having to support herself through poorly paid manual labor.

Both of them have serious concerns about their future prospects as they continue to age. It’s a big, big worry for them.

If you gave your inheritance to these two ladies, I am 98+% sure they would have their anxiety levels go down and their overall enjoyment of their remaining time on earth go up. So long as you don’t feel any worse, we’ve got a pareto efficient situation on our hands :-) . Of course, there is some possibility that by some roundabout way and influx of $25,000 would end up making them worse off, but you could say that about literally anything. Nothing in life is certain, but the above scenario is as likely to lead to an overall increase in human happiness (2 better off, no one worse off) as anything can possibly be, imho.

But as some Sufi once said (to paraphrase) the problem with charity is that people all to often regret their being charitable.

Another solution that would definitely increase happiness would be to have the whole lot of it converted into, say, 20 pound notes (if that’s a thing) and to then distribute them to the homeless when they’re sleeping or just hanging out and not expecting to be handed a 20. They will definitely experience an increase in happiness and, again, if you are at least indifferent, there will have been an overall gain in human happiness. If you can figure out how to share in their joy at this undeserved good fortune of theirs, you can make it even more effective.

Thanks for being so forthright about personal money stuff, by the way.

I believe that true happiness is living in a basement with next to no bills with no one around who is constantly nagging and trying to emotionally manipulate you. Happiness is separating yourself from these perpetually malcontent and dissatisfied!

I believe that the happiness quotient around the world would rapidly rise if all the hypergamus grifters out there were left alone with their cats. Finally the people capable of finding peace and self validation would be free to experience all the contentment and happiness they want, while the other half of the population can remain just as unhappy and needy as they always were.

So let this be a lesson: to improve the happiness of the world, walk away from the miserable people in your lives!

I’ll tell you what makes baron layard happy:

Being a Baron

Collecting 600 GBP per diem everytime him and his wife check in to the house of lords

The thought of the increase in economic performance if everyone had sufficient counselling to manage their misery.

Dismissing people’s quite natural resentment of inequality as a paradox.

The idea that having enough money isn’t that important

Knocking out a well funded annual happiness report with Jeffrey Sachs

Having a wikipedia entry that elides his role in the immiseration of many russian people.

The following year I was again in Moscow and met with Professor Richard Layard, of the London School of Economics, who was advising on economic reform. He told me that he and a colleague had boarded a Moscow bound plane in London with the idea that reform had to be carried out gradually and with care. However, by the time they had arrived in Moscow they had decided that it would be best to implement reform as quickly as possible, including the use of “shock therapy”. They thought there was a “less than 50 per cent chance of this working”, but that it was “worth a try”!

I was stunned. It was Layard’s first trip to Russia, but flush with enthusiasm he was willing to disregard his ignorance and offer such “hawkish” advice on the basis that it was “worth a try”.

There is a theory I have heard that I will paraphrase, though the percentages should not be considered definitive. I would be interested in what others think re: the percentages and the theory in general. Personally, I think it has some merit.

It is pretty clear to me that those who act purely out of self-interest have been winning the ideological battle lately, and this makes for a generally unhappy society, as non-psychopaths do not want to have to compete with psychopaths in order to just get by and live an ok life.

Time for that to change, imo.

Thanks for posting this. I would only add that they (those driven by self-interest) are winning the ideological battle, in part, because their message has infiltrated the media so thoroughly. Many of it’s proponents OWN our media outlets and aggressively push that ideology. Media in the U.S. needs a complete overhaul.

The 24 hour news cycle – or rather, the 24 hour rubbernecking is sickening. I do not watch news anymore on TV and am better off for it.

The dominance of the ideology of competition has created a really toxic social environment in the West imo. Some people prefer to base their opinions of themselves not on who they can “beat” in any given competition, but rather on how they live up to their own expectations. Some people prefer not to compete with themselves or others, and are happy to just go about their own business. Having competition and competitiveness at the foundation of a dominant social ideology creates a dynamic in which those who are not inclined towards competitiveness will always have to compete with those who are more naturally inclined to it, often resulting in a descent to the lowest common denominator for the competitive and frustration or depression for those less inclined towards competitiveness.

That said, there’s nothing wrong with competition and competitiveness per se (and I’ve been known to get a bit competitive on the dart board and ping-pong table on occasion), but it is a poor ideological foundation for a society to be built on imo, as things like love and kindness are much more important to the overall wellbeing and happiness of any given society.

The lowest common denominator for the competitive = pursuit of wealth by any means and to the exclusion of all else.

Sorry, should have explicitly stated that in the above comment.

Adding: Personally I couldn’t even read the posted piece. While it may have some validity, as soon as I looked at it I knew it would make me miserable to read it, as it seems to me to be a misguided attempt to quantify happiness.

Whilst the direction of Andrew Clark’s work is important, one of the reasons I am glad to be out of academia is that happiness (or life satisfaction), but perhaps more importantly, its measurement via rating scales, continues to gain ground.

Let’s be clear here: rating/Likert scales are not good. They were discredited in the academic marketing literature around the turn of the millennium. Plus in health a group at one of the universities in NY concluded pretty much that older people use a different part of the scale, independent of everything else you can possibly think of. I never managed to publish the British equivalent but I saw exactly the same phenomena – older people can be doing terribly on a whole host of factors in life but still say things like “9 out of 10” for happiness. And don’t even think about comparing across countries…..

At least some of the groups working in happiness research recognise that person A might be thinking about a completely different domain of life than person B when answering global life satisfaction/happiness questions (despite whatever instructions the researcher has given). It has led them to ask about “relationship satisfaction scores”, “health satisfaction scores” etc. But you then return to a key issue of how to aggregate across domains?

Those of us who followed Amartya Sen’s approach to measuring and valuing welfare – the Capabilities Approach – solved this using choice models. People reveal how much they’d trade loneliness against independence and such answers form the aggregation weights. Sen of course isn’t keen on individual measurement/valuation of capabilities but those implementing the approach recognise it must be done somehow.

Incidentally Clive’s issues would be naturally captured by our instruments. e.g. the ICECAP-O would capture the fact he doesn’t feel he’s doing sufficient things that make him feel valued etc.

I don’t trust this article. It sounds like a reversion to Freudianism: blame the parents and epecially the mother. Blame mental illness — an individual problem, which can be addressed without confronting any of the problems of society — rather than examining the stresses that come from poverty, insecurity and injustice. I have a friend who used to work with people who were mentally ill and living outside. The best treatment he found was getting the people into an apartment. Their anxiety and depression decreased, as did their alcohol and drug use.

I had much the same reaction to the table that placed ‘Abolish Depression and Anxiety’ as a factor on the same level as raising incomes, decreasing unemployment and increasing physical health.

I realize that a certain amount of depression/anxiety is a result of genetics or upbringing, but, as the Case/

Deaton report seems to indicate, even more is the result of external factors over which the person has little or no control; workplaces moving out of the area, mass unemployment, gutting of communities and social support systems; a whole domino of effects that influence the mental and emotional health of entire towns and classes. And their children.

Great wealth does not produce happiness, but not having to worry about paying the rent/mortgage, buying food and shoes for your kids, or yourself, or fending off bill collectors, sure increases one’s sense of well-being.

Many of the things seemed inseparable. Like even if one does suffer from life long anxiety, living in a ever more precarious economy with no safety net does not exactly help that. And neither is the anxiety helping one to live and yes sad to say *compete* (as we have to for jobs) in that economy.

And whether someone is partnered is more important than economics they say, but of course although it means many other things, partnered often means more economic security (not to even be cynical about it or posit any gold-digging at all, but just two incomes is more security than one). And it’s shown in poverty stats, unpartnered women are most likely to be poor in old age etc..

Maybe the mother is to blame, but the mother is not to blame for being to blame (well unless there is overt child abuse then the parents may be directly to blame no bones about it). But from hearing folks like Gator Mate, many times it’s things like maternal stress hormones and stuff that can have a negative effect. And the mother is stressed by a combination of current life circumstances, and her own personal programming that dates back to her OWN childhood and time in utero etc.. So there truly is cause without much agency, or in other words fate.

But yea crappy economics makes this happen more often than it would otherwise obviously, and a crappy economic system that doesn’t value human beings at the end of the day period (nor other life forms it goes without saying). If the economy was about valuing human beings it would be entirely different period, and even people damaged by childhood might have real hope of healing more rather than continually being re-injured by the brutality of the world. But this economic system is just about slavery to the rich so what does anyone really expect? That’s all it is.

I can see where “money does not bring happiness” and that a reduction in anxiety and depression can be achieved by other means, perhaps. However, in the country where I live (France) the common practice is to medicate depressed and anxious people.

Giving people enough drugs so that they won’t feel miserable may be useful but it fails to address the root cause of “misery”. It is interesting that the heading of Table 4 speaks of the cost of reducing the number of persons in poverty, where they probably mean misery. Someone obviously equated the two notions.

GIs get the “medicate until stupid” treatment, both while in the

servicemilitary and once subjected to the tender mercies of the VA. Heavy psych drugs as “treatment” for too often hastily and poorly and even cruelly developed and flat inaccurate “diagnoses” that militate in favor of drugging. And refusal to accept the medication is deemed “noncompliance,” a la the recently passed “21st Century Cures Act,” H.R. 6, which allows “the government” to stick you in the psych ward on a doctor’s say-so. One of those “we don’t know what’s in it, have to pass it to see how it works and what it contains” 900-plus pages “grab bags,” one of several last F***-YOUs that Obama is signing on the way to his payday. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/21st-century-cures-act-congress-health-care-passed/.Something in it for everyone with a C Street Lobbyist on line.

Considering the damage that the human species does to its home planet and to all of the other species that also call that planet home, concern about the happiness of humans seems misplaced.

The problem is ignoring unhappy people is going to have a negative impact on everyone, the planet and other species- which includes you. We just have to accept that we must work with the humanity we have rather than the humanity we wish we had. Much better than just ignoring them.

Actually, I’m no longer concerned about this human’s happiness, but I understand your point.

Income doesn’t make you happy, but having more income than your societal competitors does. The OECD technicians naturally hold the crucial instrumental variable constant – they can’t conceive of life any other way than a rat race.

A collection of institutions can require that you exist to serve the economy. Or it can ensure that the economy exists to serve you. The former condition, imposed by OECD economies, produces invidious misery. No shit, Sherlock. What do different conditions produce?

If these researchers weren’t so abjectly indoctrinated, they could easily gauge the degree to which national economies serve you. The qualitative detail is here:

http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/TBSearch.aspx?TreatyID=9&DocTypeID=5

ECOSOC review evaluates ICESCR treaty parties’ success in devoting resources to the means of life. The ICESCR is a commitment to establish national economies that serve humans beings. Regress subjective well-being with a metric based on that and see what you get. Compare economies that serve humans with US-style treadmills that pile up dollars and sum them across economic predators and prey.

You want happiness? After satisfying fundamental needs, such as food and shelter, do things that you enjoy. Immersive tasks are very good; one wants something that is challenging, but not overwhelming. Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of Flow is quite relevant.

I agree with Eleanor. There’s a reason our society has high rates of anxiety and depression. We need to address those as it’s a cultural and societal problem.

It’s like treating kids for ADHT instead of changing the repressive and confining school environment.

“…if we could abolish depression and anxiety, it would reduce misery by as much as if we could abolish all of poverty, unemployment and the worst physical illness.”

Are depression and anxiety always organic conditions in those who experience them or are there good reasons for them… like poverty, unemployment and physical illness? Or knowing that either Clinton or Trump would be POTUS? It could be argued that we have a moral imperative here to be miserable, huh? How does one abolish such depression/anxiety and is it always a good idea to do so? Prozac? The literature suggests prozac and other similar (anti-human) meds lead many users to suicidal thoughts and actions, yes?

Which leads to another paradox… i remember reading, many years ago, an article in the Sunday NYTimes magazine which concluded that satisfaction/happiness results from one’s assumptions being proved right, that someone who has their expectations fulfilled in any given day sleeps better at night. It used the examples of realists (usually called pessimists), who wake up grumpy, facing “another day” of the same old same old because they knows things are not going to get much better, as opposed to optimists who wake up with a song on their lips, sure that everything can be put right in their world. The study concluded that by the end of the day the realist/pessimist was more satisfied (fulfilled expectation) than the optimists who’s high hopes were dashed by the reality of our daily grind.

I’m not convinced we should constantly lower our expectations in an effort to attain happiness/satisfaction (although it works for me when I need it to) because I have a real problem with the suggestion that happiness/satisfaction should be a constant state or goal in life, especially if it comes at the expense of serious contemplation. Someone smarter than me once offered that critical thinking/intelligence (especially in a world gone mad) is the sine qua non of depression and anxiety.

Krishnamurti says that being well adjusted to a sick, mal-adjusted society is the antithesis of being well adjusted.

PS – I should add that I did some serious lowering of my expectations as a professional musician and it resulted in my handling the ups and downs of that scary business more easily. Attempting to do the same with anti-anxiety meds just left me uninterested and uninteresting.

I subscribe to the Epicurean definition of happiness — ataraxia, the absence of suffering and worry, otherwise known as tranquility.

Since being a modern adult means you’re constantly worrying about something or other even in the best of times, I feel that we’ve got a long way to go culturally before political policy can do anything about it.

America and some other select countries have a security of person with much higher expectations of normalcy, so much so that it causes stress to these catagori, if the least little hazard is experienced, they suffer the princess and the pea syndrome! They loss sleep!

You can be unhappy with something but not anxious or depressed; but can you be happy at the same time as being anxious or happy at the same time as being depressed?

We have a statue of a local man who retired rich in his thirties and devoted his life to helping his fellow man as his ‘riches lay not so much in the largeness of his means as in the fewness of his wants’

I would remind us all of one of yesterday’s links:

http://www.raptitude.com/2016/12/five-things-you-notice-when-you-quit-the-news/

I don’t see the negative influence of rapt attention to media which purports to be news in any of the graphs, but as reflected in the comments to the above article, quitting such an obsession (and that it has become for many) to be abreast of things in this manner does contribute enormously to what I would call personal equilibrium.

And maybe even when the news is accurate and unexploitative (not sure that is a word – spellcheck thinks it isn’t – but I like it) too much exposure is a bit like Through the Looking-glass. I’ve sworn off the addiction, and I know I am happier for it.

(I didn’t think the link was discussed yesterday – just wanted to thank you, Lambert, as I did appreciate it.)

“For most of life, nothing wonderful happens. If you don’t enjoy getting up and working and finishing your work and sitting down to a meal with family or friends, then the chances are you’re not going to be very happy. If someone bases his [or her] happiness on major events like a great job, huge amounts of money, a flawlessly happy marriage or a trip to Paris, that person isn’t going to be happy much of the time. If, on the other hand, happiness depends on a good breakfast, flowers in the yard, a drink or a nap, then we are more likely to live with quite a bit of happiness.” – Andy Rooney

Unhappiness is as elusive as happiness. I believe they are usually chemical. Not to discount the misery of existence, but I think it’s as important to acknowledge unhappiness as to acknowledge happiness. And in almost a welcoming way. Because it’s just good to be real. I had a friend who had lived an independent life, working forever, middle class, very smart woman who occasionally resorted to prozac and she would be so impervious to all and everything on those days. One time we were talking about someone who seemed to be living a charmed life and my friend said, “I’m sure she isn’t any happier than I am.” And ever since then I have appreciated other peoples’ unhappiness more than their apparent happiness. And it strangely makes me content. It’s not like schadenfreude – it’s more like hugs.

How Aldous Huxley of you to pinch pennies by treating the anxiety and depression caused by economic misery instead of addressing the actual economic injustices of unemployment and rent-seeking.

Was no one else reminded of the choices that lead to Brave New World? We need a way forward that doesn’t run through that or 1984.