Yves here. Steve Keen gave a presentation in 2016 which identified economies that were at risk of a serious recession, including China, South Korea, and Finland, if their level of debt to GDP merely stabilized. This talk is fast-paced and very much worth watching.

As you’ll see, Don Quijones highlights how corporate debt levels have exploded in China

By Don Quijones, of Spain, Mexico, and the UK, and an editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

Chinese corporate defaults this year through April are 3.4 times the amount last year.

Since the global financial crisis, the total value of outstanding corporate bonds has doubled, from around $37 trillion in 2008 to over $75 trillion today. But the growth has been far from even, with non-financial debt growing much more rapidly in certain jurisdictions. As the volume and price of this debt has grown, so too has its riskiness. And that could be a recipe for disaster, warns Sir John Cunliffe, deputy governor for financial stability at the Bank of England.

In the US, non-financial debt is up 40% on the last peak in 2008. Cunliffe expressed even greater caution concerning emerging markets, where corporate debt as a proportion of the global debt pile has grown the most over the past 10 years. “Emerging market debt now accounts for over a quarter of the global total compared to an eighth before the crisis,” Cunliffe said.

Before the financial crisis, emerging market companies were issuing a total of $70 billion per year in bonds, according to OECD data. That was before the world’s biggest central banks embarked on the world’s biggest monetary experiment, in which companies the world over were invited to participate.

By 2016, emerging market corporations were issuing ten times more money ($711 billion) than before, much of it in hard foreign currencies (mainly euros, dollars and yen) that will prove much harder to pay back if their local currency slides, as is happening in Turkey and Argentina right now. Although bond issuance by emerging market companies declined by 29% in 2017 and remained around the same level in 2018, it is still approximately 7.5 times higher than the pre-crisis level.

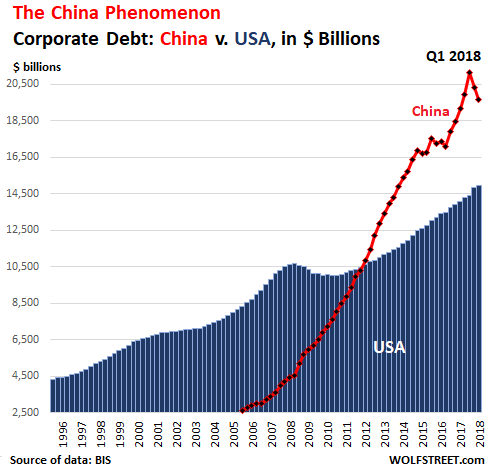

Much of the increase has been driven by China as it transitioned from a negligible level of issuance of corporate debt prior to the 2008 crisis to a record issuance amount of $590 billion in 2016. During that time the number of Chinese companies issuing bonds soared from just 68 to a peak of 1,451 and the total amount of corporate debt in China exploded from $4 trillion to almost $17 trillion, according to BIS data. By late 2018 it had reached $19.7 trillion.

“There has been a persistent buildup of private debt to record levels in China,” Cunliffe said. Much of this increase took place in the direct aftermath of the financial crisis. The largest increases have been in the corporate sector, mainly in state-owned enterprises. At last count, China’s corporate debt-to-GDP ratio was 153%, enough to earn it seventh place on WOLF STREET’s leaderboard of countries with the most monstrous corporate debt pileups (as a proportion of GDP), 18 places above the US. This chart compares the rise of non-financial corporate debt in China and the US:

The rate of growth and level of debt in China have passed the points where other economies, advanced and emerging, have experienced sharp corrections in the past, noted Cunliffe citing research carried out by the Bank of England.

Since early 2017 the Chinese authorities have been scrambling to deleverage its corporate sector and shrink its shadow banking system, with a certain degree of success (the hook in the chart above): corporate debt-to-GDP ratio has fallen in the last two years by almost 10%. However, in the face of slowing economic growth, the Chinese government has dialed back some of these reforms as concern rises that a sharp slowdown in growth would make China’s elevated debt levels even less sustainable.

And if things get seriously sticky in China’s debt markets, it won’t take long before they’re felt elsewhere, Cunliffe cautioned:

The Chinese economy is now pivotal to regional growth and one of the main pillars of world growth and trade. As well as the economic effects and effects directly through banking exposures, it is likely that there would be a severe impact on financial market sentiment, [as happened] in 2015 when a period of sharp correction in domestic Chinese financial markets sparked a correction in US financial assets.

Problems once again appear to be on the rise in China. Chinese companies defaulted on 39.2 billion yuan ($5.78 billion) of domestic bonds in the first four months of 2019, 3.4 times the total for the same period of 2018, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. For the moment, there’s little sign of the problems spreading far beyond Chinese borders. In most advanced economies, as well as quite a few emerging markets (Turkey and Argentina excluded), bond spreads — the amount charged for risk, be that credit risk or liquidity risk — are still at or near historically low levels.

But conditions can change on a dime, as the short-lived drama at the end of 2018 amply demonstrated. Between mid-October and the end of the year spreads on investment grade bonds widened by around 50 bps, all on the back of “relatively modest amounts of news,” Cunliffe noted. “Since then, these moves have fully retraced – spreads at the start of May were the same as they were in mid-October last year. Bonds in other currencies and high yield bonds went on a similar round trip.”

When it comes to expectations about the value of debt, the market can be highly susceptible to changes in sentiment, meaning a “correction can come very quickly”. As Cunliffe warns, given the “current compression of risk pricing,” not to mention the sheer abundance of poor quality, mispriced bonds out there, “such a correction could be a sharp one.” By Don Quijones.

“Zombie firms,” kept alive by low interest rates, account for up to 14% of UK companies. Read… Businesses in “Critical Distress,” Bankruptcies Surge in the UK

China meets MMT. The debt of China’s stat e owned entities, is the state’s money owned to the Sovereign state,

Per MMT this is an accounting matter, and not a problem.

owned should be owed.

I hate using a smartphone. :(

Switch to Huawei.

The USG suggests that would be the wrong way.

The Chinese Government could spy on me. However there is the long line of Google, Facebook, AT&T, various three letter US agencies, credit bureaus, my bank and others who got there first.

So this always raises the question that panics finance – Why should any money ever earn interest? Debt is the only price-fixed commodity, which costs nothing to produce and which is controlled using scarcity in order to make money on money. Debt/money makes money 2 ways: inflation and debt service, and gets all of its original investment back as well which in the end has no where left to go but ponzi because the underlying economy has been burdened simultaneously with inflation (compounded interest kills economic balances) and debt service. And everybody has gone bankrupt. Clever.

Thanks Susan, that’s a point Aristotle made. If the debt is in cows and sheep you get to keep the natural increase from new births and the milk and wool but metals and paper money are sterile.

Question: What is non-financial debt?

indeed. that’s a very cosmic question and the only one at this point…

My wife often says I owe her. Payback is usually chores or watching Korean television.

Good question. I`ve read “debt not included in the financial sector (balance sheets i guess)”

For instance corporate bonds marketed as fixed-income securities.

The term non-financial debt is used to refer to the aggregate of debt owed by households, government agencies, non-profit organizations, or any corporation that is not in the financial sector. This can include loans made to households in the form of mortgages, or amounts owed on credit cards.

Whether that is what the author thinks it means, I don’t know.

yeah..but China’s invested in gold..so price of gold goes up-it balances /offsets their debt.

hmm..question:.now who coulda knowd gold-backed currency survives and debt-backed monopoly usd doesnt?

answer: everyone on the planet w even half a brain

Sorry — “gold backed currency” is no less a mirage than the rest of them

ALL currencies depend upon the mutual faith in human agency that they represent, regardless of the atoms used in the representation

gold’s hold on the human imagination is the secret of its “value”

Aside from the topic of the post, but relevant to a lot we’ve discussed:

Why is the central bank of the UK the “Bank of England?” Doesn’t that make the colonial attitude all too obvious?

The Bank of England was established shortly before Scotland joined the union. Wales was just ignored as usual. Fact is in those days they weren’t self-conscious enough to realise they had a colonial attitude. They were on top and that was simply the natural order.

I believe that besides accounting the outstanding debt it needs to be understood what is the collateral that supports the debt in each case. The case of China. How much of corporate non-financial debt depends on real estate? raw materials? others? it would help to know the risk attached.

I think it’s time for central banksters to worry about being fitted with soon-to-be-fashionable form-fitting hemp neckties.

There ! Fixed …

And bet on the ‘factors’ out of the CCP to sell themselves the rope, as per Lenin. (The definition of a ‘mixed economy!’)

The secrets of the monetary system have remained completely hidden during globalisation.

The US tried to balance the Government budget when running a large trade deficit.

This is the US (46.30 mins.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ba8XdDqZ-Jg

These are the actions of people who don’t understand the monetary system.

Money and debt.

If there is no debt, there is no money.

The money supply ≈ public debt + private debt

Money comes out of nothing and is just numbers typed in at a keyboard.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Bank loans create money and bank repayments destroy money and this is where 97% of the money supply comes from.

Money and debt are like matter and anti-matter they come out of nothing and go back into nothing.

The haphazard way that nations create their money supply means bank credit has to be managed well to ensure a stable money supply.

Policymakers had no idea and embarked on financial liberalisation, leading to frequent financial crises. This is just not something anyone would do that understood the monetary system.

Even the BIS seem to be in the dark as the Basel rules are based on the assumption banks are financial intermediaries, but they are not.

Richard Werner explains:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EC0G7pY4wRE&t=3s

This is RT, but this is the most concise explanation available on YouTube.

Professor Werner, DPhil (Oxon) has been Professor of International Banking at the University of Southampton for a decade.

The money supply ≈ public debt + private debt

We talk about deleveraging as though this was easy when a shrinking money supply causes debt deflation.

We should never have got to where we are now, but our mainstream policymakers didn’t understand the monetary system.

As you don’t want the money supply to shrink, you need to take on debt in a way that the economy can sustain.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.53.09.png

Before 1980 we (UK) were doing it right.

Debt rises with the money supply and you need to ensure the economy can stand the debt repayments. If GDP grows with the debt you won’t have a problem. Banks were lending into the right places that result in GDP growth (business and industry, creating new products and services in the economy).

After 1980 we were doing it wrong.

Financial liberalisation; where bankers could earn more money from lending into all the wrong places that don’t grow GDP with the debt (real estate and financial speculation).

At 25.30 mins you can see the super imposed private debt-to-GDP ratios.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

Japan, the Euro-zone, the UK, the US and China.

The world has been loaded up with debt, but it cannot handle the debt load as GDP didn’t grow with the debt.

The money supply ≈ public debt + private debt

How do you get the overall debt levels down to something sustainable without pushing the economy into debt deflation?

There aren’t a lot of terms to play with.

Adair Turner took over at the FSA when Lehman Brothers collapsed and this gave him the incentive to find out what was going on.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LCX3qPq0JDA

Adair Turner has realised the current situation is unsustainable and requires Government created money.

You need a source of money to maintain the money supply that doesn’t add to the overall debt and allows the debt to be paid down.

China has made all the classic mistakes that everyone makes who uses neoclassical economics.

They have inflated both real estate and stock markets with bank credit. They really got taken in by all that price discovery and stable equilibrium stuff.

Their stimulus since 2008 has gone into all the wrong places that didn’t grow GDP; the private debt soared, but GDP didn’t. It’s a classic mistake.

At 25.30 mins you can see the super imposed private debt-to-GDP ratios.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

Japan, the UK, the US, the Euro-zone and China.

They have already learned the private debt-to-GDP ratio and inflated asset prices are indicators of financial crises.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

The West’s “black swan” is a Chinese Minsky Moment.

As the Chinese understand the problem they are not going to try and cure a debt problem with more debt as we have been doing in the West since 2008. In the West, central banks dropped interest rates to the floor to squeeze more debt into our economies.

Chinese bankers had inflated the Chinese stock market with margin lending in 2015.

Set the scale to 5 years to see what happens to the Chinese stock market as their bankers inflate it with margin lending.

https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/SHCOMP:IND

The wealth is there one minute and gone the next, it wasn’t real wealth. GDP measures the real wealth in the economy.

The Chinese wanted increased domestic consumption, but let housing costs soar.

It was that neoclassical economics again, but they have now learnt that high housing costs eat into domestic consumption by reducing disposable income.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

Once they have sorted out the mess left behind by their technocrats trained in neoclassical economics they will be ready to start growing again, but it could take a while.

At least they have worked out what the problems are, unlike their Western counterparts.

The engines of global growth were fuelled by debt.

They gradually spluttered and stalled when they couldn’t take on any more debt.

There was one engine of global growth left, China.

It gradually spluttered and stalled when they couldn’t take on any more debt (Minsky Moment ahead).

What does it look like?

At 25.30 mins you can see the super imposed private debt-to-GDP ratios.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

Same ideology, same economics, same mistake.

We really should have known better.

The 1920s roared with debt based consumption and speculation until it all tipped over into the debt deflation of the Great Depression.

No one realised the problems that were building up in the economy as they used an economics that doesn’t look at private debt, neoclassical economics.

Same economics, same mistake.

(Have a look at the chart above)

I assume that the clever raising of tariffs by the US is helping stabilize the situation and reassure the markets in the context described above