Yves here. This thesis, that gender-image-defying boys and girls and boys grow up to be men and women that aren’t as well received as they ought to be in the workplace. These individuals one assumes have also either managed to resist or been unable to adapt to conformity pressures. This is not the same as “stereotype threat” where girls don’t do as well in math because they get subtle (and when older, often overt) messages that they aren’t supposed to do well. One proof that this result is significantly due to nurture and not nature is that in the Middle East, where math skills are not prized among men, girls and young women typically do better at math than their male peers.1

By Robert Kaestner, Research Professor, Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago, and Ofer Malamud, Associate Professor of Human Development and Social Policy, Northwestern University. Originally published at VoxEU

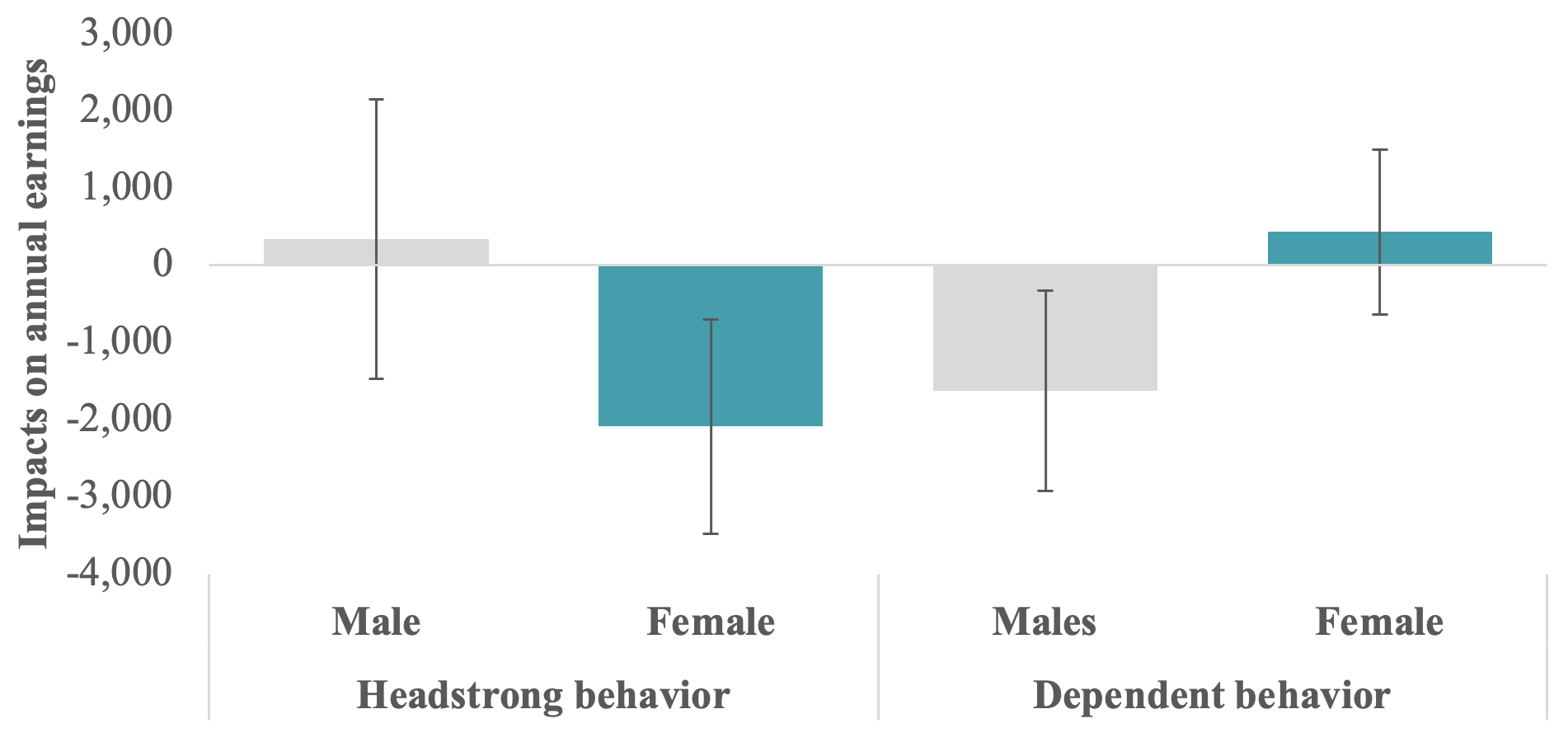

The persistence of the gender wage gap suggests it may have roots extending back into childhood. Using data from a US longitudinal survey, this column examines how gender differences in adult earnings correspond to various childhood behaviours. Results indicate that women (but not men) who exhibited headstrong behaviour as children incurred significant earnings penalties as adults, while men (but not women) who exhibited more dependent behaviour as children were penalised. Whether these patterns are the result of nonconformity to gender norms and stereotypes warrants further attention and study.

Despite substantial convergence in pay and employment levels, gender differences in the labour market persist (Azmat and Petrongolo 2014). Among potential explanations for these disparities are gender differences in preferences (Booth et al. 2012) and labour market discrimination (Booth and Leigh 2010). In recent work (Kaestner and Malamud 2021), we explore the role of gender differences in the labour market returns to various dimensions of child behaviour.

A substantial literature has documented the significant relationship between cognitive skills, measured in childhood and adolescence, and adult earnings (e.g. Murnane et al. 1995). More recently, studies have also shown significant associations between adult earnings and childhood ‘non-cognitive skills’, such as socio-emotional behaviours and temperament (e.g. Heckman et al. 2006, Papageorge et al. 2019). However, there has been relatively little research on gender differences in the labour market returns to childhood ‘non-cognitive skills’, especially when disaggregated into specific domains of behaviour.

We use data from the Children of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (C-NLSY79) to examine associations between several distinct child behavioural problems measured at ages 4 to 12 and adult earnings measured at ages 24 to 30. Our measures of child behavioural problems are drawn from an abbreviated version of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), reported by parents and “designed to measure some of the more common syndromes of problem behavior found in children” (Zill 1985). The CBCL is one of the most widely used assessments of children’s emotional and behavioural problems and has been shown to have strong predictive validity. Like the CBCL on which they are based, the measures of behavioural problems in the C-NLSY79 have also been shown to have strong predictive validity (Parcel and Menaghan 1988).

The specific behavioural syndromes recorded in the C-NLSY79 are:

- antisocial behaviour

- anxiety/depressed mood

- headstrong behaviour

- hyperactive behaviour

- dependent behaviour

- peer conflict.

Items that constitute the behavioural scales are intuitive. For example, children score high on the headstrong scale when their caregiver reports that he or she argues too much; has a strong temper and loses it easily; is disobedient at home; is stubborn, sullen, or irritable; and is rather high strung, tense, and nervous. On the other hand, children can score high on the dependent scale when their mother reports that he or she demands a lot of attention; clings to adults; cries too much; and is too dependent on others. We average the scale scores across all surveys for which the child is present between ages 4 and 12 in order to improve reliability.

Main Findings

We find large and significant earnings penalties for women who exhibited more headstrong behaviour and for men who exhibited more dependent behaviour as children. There are no significant or economically meaningful penalties for men who were headstrong or for women who were dependent. While other child behavioural problems are also associated with earnings, their associations do not differ significantly by gender. Below is a graphical representation of the earnings differences associated with headstrong and dependent behaviour by gender (for the full set of estimates across all child behaviours, see Table 2 in Kaestner and Malamud 2021).

Figure 1

These results are robust to alternative specifications of earnings (e.g. levels or logs) and child behaviours (e.g. linear or categorical). The results are also similar with and without adjustment for differences in academic achievement or family background, and when allowing for the effect of family background to differ by gender. While we are careful to avoid making strong causal claims about the estimated relationships, these analyses address some of the more important and potentially confounding influences of family background.

The differential returns to dependent and headstrong behaviour by gender are not mediated by significant gender differences in the associations between child behaviours and the likelihood of employment, work hours, marriage, fertility, or self-esteem. Nor do we find gender differences in the associations between child behaviours and adult personality traits, mental health (CESD), or the probability of being in good health. While we do find that men who were characterised as dependent are significantly more likely to report being in poor health – and this association differs significantly from the corresponding figure for women – these differentials are too small for health to be a significant mediator of the gender difference in the association between dependent behaviour and earnings.

However, we do find heterogeneous gender differences in the returns to headstrong and dependent behaviour by education and occupation. This heterogeneity is suggestive of the role of workplace settings, and perhaps workplace prejudice, in explaining gender differences between these child behaviours and early adult earnings.

Discussion

One potential explanation for our findings is that children who exhibit behaviours that deviate from gender norms and stereotypes may be penalised in the labour market. In our setting, dependent behaviour is more prevalent among girls than boys while headstrong behaviour (along with other child behaviours) is more prevalent among boys than girls. At the same time, numerous public opinion surveys suggest that certain traits, such as stubbornness and decisiveness, are more associated with males while other behaviours, such as sensitivity and being emotional, are more associated with females (Eagly et al. 2019). This hypothesis is consistent with the role congruity theory of prejudice, which posits that men and women who behave in ways that are contrary to expected behaviours are often subject to prejudice (Eagly and Karau 2002). Indeed, men and women who do not conform to gender norms and stereotypes in the labour market have been shown to suffer social and economic sanctions (Akerlof and Kranton 2000, Brescoll and Uhlmann 2008).

Nevertheless, more research is needed to distinguish this hypothesis from alternative explanations. For example, do the moderating effects of gender arise because of differences in actual productivity, or because colleagues and supervisors have negative perceptions of headstrong women and dependent men? The former could arise if behaviour is more pronounced by gender while the latter is consistent with a bias due to non-conforming gender behaviours. Another important question is why other childhood behaviours – such as hyperactive, anti-social, and peer conflict – do not differ in their associations with earnings by gender. Like headstrong behaviour, these behaviours have strong correlations with adult earnings and are more prevalent among boys than girls. So why is the moderating role of gender absent in the case of these behaviours? Perhaps these behaviours are less associated with adult gender stereotypes and therefore not perceived as gender non-conforming behaviours. Or perhaps these behaviours do not lead to negative perceptions on the job because they do not affect social interactions. Further research is needed to answer these questions as well.

See original post for references

_____

1 At the middle and top, these are clientilist societies, so who you and your family know counts for vastly more than technical achievement.

First of all, thank your for sharing this. I haven’t seen this issue approached this way using this data set before, which is amazing because the gender earnings gap has been studied a lot. The analysis looks like a classic “elegant in its simplicity” study.

But I’m disappointed the authors here did not give a deeper discussion of socioeconomic status or for that matter, race. They say the results stay the same even when controlling for “family background” but that term needs some defining here. My apologies if I missed it.

If they did find that socioeconomic status and race were not relevant to the phenomenon they are describing, that itself is noteworthy and surprising, at least to me.

In working class communities I’ve seen first-hand, academic achievement tends to be less prized among boys (though still prized) since it is offset by sports to a much greater degree than for girls, especially in the time period under consideration.

Putting it crudely, in the PMC and up, boys dream of becoming executives and girls of becoming executives’ wives, while in the working class, boys dream of being foremen and girls of being secretaries (who actually need more of that school learning), at least in the 1970s-80s.

Putting it crudely, in the PMC and up, boys dream of becoming executives and girls of becoming executives’ wives, while in the working class, boys dream of being foremen and girls of being secretaries (who actually need more of that school learning), at least in the 1970s-80s.

Pretty sure this has changed significantly over the decades. eg. these days a girl who wants to become a secretary would be a very, very rare exception.

Which reinforces @Joe Well’s point.

The NLSY79 Cohort is a longitudinal project that follows the lives of a sample of American youth born between 1957-64.

It’s a very valuable antique dataset.

People change, shy dependent children can become headstrong adults and vice versa. Especially when you consider “headstrong” behaviours are punished in children.

Additionally, workforce participation creates a whole other “maturity” process, young employees may be shy at first but then build confidence as they learn to navigate projects or the workplace culture.

Employers also differ in that some insist on conformity to rigid parameters, antiquated notions of “leadership” as exclusively tied to assertive/agressive behaviours, other employers may be very good at adapting roles and performance measures to employee unique strengths and characteristics, may be good at bringing out contributions from and giving voice the quiet ones around the table.

Not sure how a study like this can control for these factors.

Finally, a LOT has happened in this space across the corporate world in the last 5 years. For example, anti-bias training and measures.

Headstrong girls? Dependent boys? Whatever do they mean, and as described by whom? By 1979 standards of “he is assertive, she is bossy” and ‘dependent’, ie “faggy” as recorded by whom? Teachers, parents, school guidance counselors and psychologists, I would guess.

‘Received in the workplace’ by whom? By supervisors or by co-workers? If pay, therefore raises and promotions, is the gauge, it is generally the supervisors and on up who determine that.

To me, this ‘study’ raises more dust than it clears. I also note that the last sentence is “Further research is needed to answer these questions as well.” Is this a grant proposal?

Disclosure: I am pretty sure I was written up somewhere as a ‘headstrong girl’. I have tended to do well in organizations and businesses that value competence, less so in orgs where the mgmt chain is most insecure.

The women who made partner first at McKinsey were pretty and ingratiating and inoffensively clever….

Measuring “outcomes” by income is inane.

I get it, income matters, but it is only a piece of what matters. A small piece.

Perhaps a more useful study would look at the effect of such behaviors on whether the person grew up to be part of a group (family whatever) that had “base sufficient per capita income” for happiness (dont the surveys show that level is what, 80k or so?)

If true, this study tells us, at most: if you want your daughter to maximize her earning potential, help her avoid being “headstrong.”

This sort of simple data point is not useful in any sort of real whole-child parenting.

Trying to justify any sort of policy (whether forcing changes to employment culture or family culture) based on a survey like this would be horrible.

Measuring “outcomes” by income is inane.

We live in a technocratic-capitalist society that is obsessed with “metrics” and where income/money is the only measure of value and worth that is accepted as valid by the ruling class. More money is always better (except when it comes to spending it on the public good….ick) so a rich kid is the best kid and the poor kid should “aspire” to become the rich kid, or at least “achieve” similar “life outcomes”.

It’s an inhuman way to run a society (they want us to be robots lol) and until this changes the gloom will continue.

I wonder if this phenomenon is more pronounced among societal elites.

The female executives with whom I worked at a major US telecommunications company in the late 1980s were not only headstrong, they aped the behavior of our overly aggressive male counterparts, smoking cigars and telling crude jokes at gatherings. I didn’t last long there.