Yves here. This post makes an interesting point about the fact that ratings agencies are grant some US government entities and private companies, now only Microsoft and J&J, AAA rating. That would be unwarranted if the US itself were impaired. This post unpacks that issue. It also addresses the differing views these agencies hold of the US reserve currency status.

I will not go to the considerable effort of taking apart the author’s fiscally orthodox beliefs, but readers are encouraged to have a go in comments.

Stephanie Kelton, in a February Bloomberg interview, argues that a downgrade was arguably warranted not on ability to pay grounds but willingness to pay, as in DOGE types and some Congresscritters seemed to think it could be OK to suspend payments, including on some Treasuries.

US debt is a non issue, bond yields and debt cost are controlled by the Fed pic.twitter.com/yjesg6nauW

— fiat money (@fiat_money) May 17, 2025

By Robert N McCauley, Nonresident senior fellow, Global Development Policy Center Boston University; Associate member, Faculty of History University Of Oxford. Originally published at VoxEU

On Friday 16 May 2025, Moody’s’ Investor Services downgraded the US Treasury’s credit from Aaa to Aa+ with a stable outlook. This first in a series of three columns sketches a stripped-down theory of the relationship between reserve currency and sovereign ratings. Then it profiles the widespread misreporting of Moody’s downgrade of the US Treasury, often written up as a downgrade of the United States as a country, and shows why it matters.

On Friday 16 May, Moody’s’ Investor Services downgraded the US Treasury’s credit rating by one notch from a golden Aaa to a sterling Aa+ with a stable outlook. Moody’s had put the US Treasury on notice 18 months before. This may have been the most significant rating action in the history of ratings, or at least the second most significant.

To appreciate the meaning of this event, this first of three columns on Vox introduces the event and sketches a basic, reduced form theory of the relationship between reserve currency and sovereign ratings. This column also profiles the widespread misreporting of Moody’s downgrade of the US Treasury, often written up as a downgrade of the United States of America as a country, and show why it matters.

In the second column, I shall dive into the empirics of the relationship between sovereign ratings and government debt burdens and the rating agencies’ view of the lift that the dollar’s reserve role gives to the US Treasury’s rating. The history of economists inferring the recipe for the rating agencies’ secret sauce is only a generation long, and during much of that time the data did not confess the role that fiscal deficits or debt must play in sovereign ratings. Ten years ago the data did, under sustained interrogation, confess. But the relationship found ten years ago sits uneasily with a US Treasury rated Aa+/AA+/AA+ by Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s (S&P), and Fitch. I shall then sketch the rating agencies different views of how the dollar’s reserve role strengthens the sovereign rating of the US Treasury.

In the third column, I ask what market prices reveal about market participants’ views of whether and how the dollar’s reserve role supports the US Treasury’s creditworthiness. Market prices are sending mixed signals about the appropriateness of the rating agencies’ opinions. Strong evidence points to the US Treasury’s no longer receiving special treatment in global bond markets. The third column closes with possible interpretations and a warning: policy would err if it were set on the theory that the rest of the world must or will buy as much debt as Treasury Secretary Bessent flogs. The risk is that market participants lend the US Treasury enough rope for it to hang itself.

Moody’s Catches Up

Moody’s was not a first mover. The move brought Moody’s rating in line with that of S&P’s. This reduced by one the number of sovereign “split ratings,” the number of which ratcheted up after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) (Amstad and Packer 2015).

In 2011, S&P put the US Treasury on watch for downgrade going into the scary Congressional debt ceiling debate. It then downgraded the US Treasury days after the debate had ended without default on the grounds of puerile governance and unsustainable borrowing. Only a decade later did investors have to sweat another scary debt ceiling debate. Moody’s also aligned its rating with that of Fitch, which called out the US Treasury’s debt trajectory and “erosion of governance” in 2023.

Moody’s was redrawing the line way, way out in the tail of the default probability distribution. By Moody’s default studies, the downgrade implied no more than a likelihood of a US Treasury default within 5 years of 0.6% rather than 0.0%. Small beer?

Stephen Cheung, White House sharpshooter, fired back on X. He missed. By the standards of the sovereign rating game, often a contact sport, Moody’s got off easy.

The following Sunday 18 May, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent went on NBC’s Meet the Press to recall what Larry Summers, of all people, said in 2011 when S&P downgraded the US Treasury rating from AAA to AA+. “I think that Moody’s is a lagging indicator,” Bessent said. “I think that’s what everyone thinks of credit agencies.” In other words, the downgrade was President Biden’s fault. The 30-year US Treasury bond traded for a time after Moody’s announcement over 5%.

On the day after Moody’s announcement, Toby Nangle in FTAlphaville was fast out of the box with the musical question, “Does Moody’s US downgrade matter?” For a chuckle, hum your way through the 111 comments.

But this is serious stuff. Moody’s wrote:

This one-notch downgrade on our 21-notch rating scale reflects the increase over more than a decade in government debt and interest payment ratios to levels that are significantly higher than similarly rated sovereigns [italic added].

Successive US administrations and Congress have failed to agree on measures to reverse the trend of large annual fiscal deficits and growing interest costs. We do not believe that material multi-year reductions in mandatory spending and deficits will result from current fiscal proposals under consideration. Over the next decade, we expect larger deficits as entitlement spending rises while government revenue remains broadly flat. In turn, persistent, large fiscal deficits will drive the government’s debt and interest burden higher. The US’ fiscal performance is likely to deteriorate relative to its own past and compared to other highly-rated sovereigns.

Now, an angle worth thought is the importance of the dollar’s predominance as global money. Back to Moody’s:

The stable outlook reflects balanced risks at Aa1. The US retains exceptional credit strengths such as the size, resilience and dynamism of its economy and the role of the US dollar as global reserve currency. In addition, while recent months have been characterized by a degree of policy uncertainty, we expect that the US will continue its long history of very effective monetary policy led by an independent Federal Reserve [italics added; fingers crossed (McCauley 2025)].

Reserve Currency and Sovereign Ratings: Cocktail napkin theory

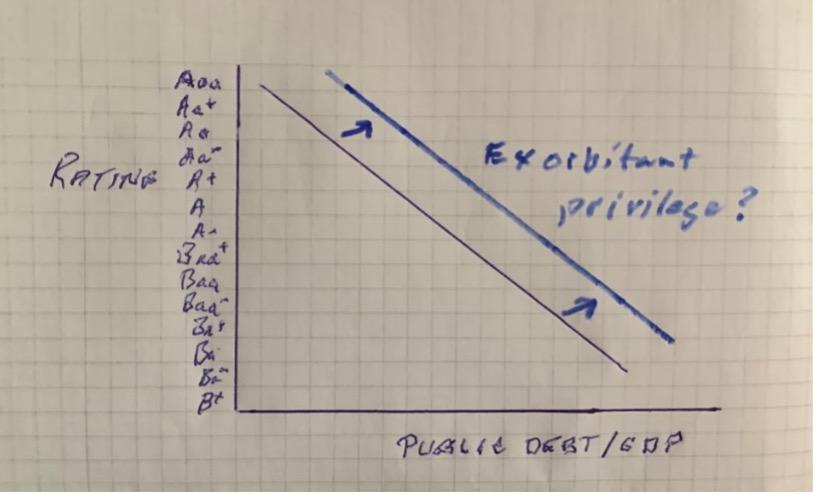

Presumably, the dollar as global reserve currency gives the US Treasury a captive investor base that eases the relationship of the sovereign rating to some measure of the government’s debt burden. Debt/GDP is on the horizontal axis in Figure 1, but slot in your favourite measure (see below). One might refer to the shift of the rating-debt curve in the northeast direction as “exorbitant privilege.”

Figure 1 Government debt burden and ratings I

Source: Author’s cocktail napkin.

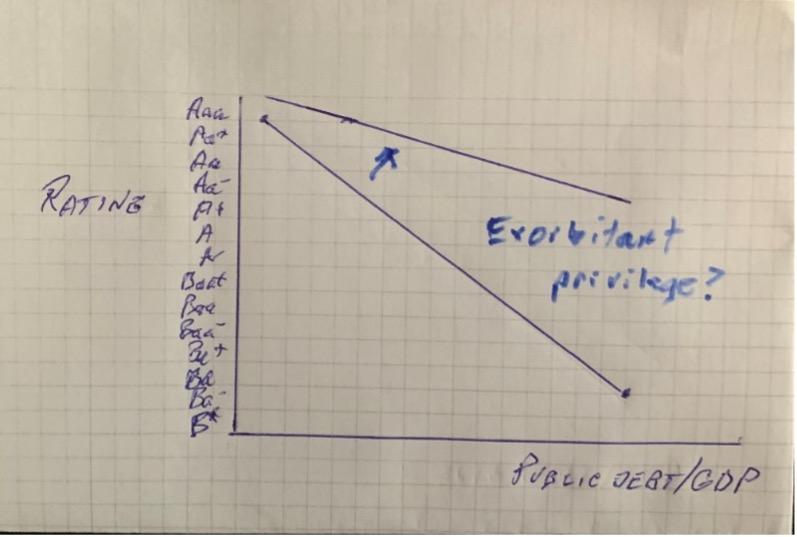

But the dollar’s reserve role could also flatten the curve. Alas, this would give Washington less of an incentive to put its house in order:

Figure 2 Government debt burden and ratings II

Source: Author’s cocktail napkin.

So much for the theory, cocktail-napkin style.

What Did Moody’s Downgrade and Why Does It Matter?

In fact, Moody’s downgrade was widely misreported as applying to the United States of America rather than to the US Treasury by:

- Financial Times veteran Michael Mackenzie in Bloomberg (although Financial Times veteran John Authors got it right on the following Monday here).

- Tony Romm, Andrew Duehren and Joe Rennison at the New York Times.

- Kate Duguid, Peter Wells and George Steer at the Financial Times.

Toby Nangle got it right in FTAlphaville the next day. Kudos to Matt Wirz and Sam Goldfarb at the Wall Street Journa land Matt Peterson at sister publication Barron’s for getting their first drafts of history right.

To be fair to the Fourth Estate, many Wall Street analysts confused the sovereign or government rating with the country rating as well. Even a careful academic, Professor Aswath Damodaran of the Stern School of Business at New York University, referred indifferently to sovereign and country ratings.

The lesson is clear. Read the press release:

The US’ long-term local- and foreign-currency country ceilings remain at Aaa. The Aaa local-currency ceiling reflects a small government footprint in the economy and extremely low risk of currency and balance of payment crises. The foreign-currency ceiling at Aaa reflects the country’s strong policy effectiveness [see Frances Fukuyama’s “Why doesn’t government work in the US?”] and an open capital account [section 899?], reducing transfer and convertibility risks [italics added].

This matters. As Moody’s said when it downgraded downgraded a slew of non-financial corporations after it downgraded both the Russian government debt and the Russian foreign currency country ceiling in 2015:

A country ceiling generally indicates the highest rating level that any issuer domiciled in that country can attain for instruments of that type and currency denomination.

If the US country credit ceiling rating were lowered, then there would presumably be no US state rated AAA by all three major agencies. Blue states Delaware and Virginia, purple states Georgia and North Carolina, and red states Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri, Ohio, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah all have the coveted trifecta of AAA ratings.

Similarly, in the event of a downgrade of the US country ceiling, among top-rated US-headquartered firms, Johnson and Johnson, rated AAA/Aaa by S&P/Moody’s, might have lost its top rating. (In “highly unusual” cases, Moody’s assigns a multinational firm a higher rating than the long-term local- and foreign-currency country rating of the home country.) Do we need to put a Band-Aid on US debt?

While the US Treasury downgrade did not drag down US states’ credit ratings, it did drag down the credit ratings of US government-sponsored enterprises that underwrite US home mortgages. On May 19, Moody’s followed up its US Treasury downgrade with a downgrade of its housing wards, Fannie and Freddie, as well as the Federal Home Loan Banks (those lenders of penultimate resort to US banks).

Prospering in a 17-year conservatorship, Fannie Mae now boasts a AA+/Aa1/AA+ rating from S&P/Moody’s/Fitch, as does Freddie Mac. The Federal Home Loan Banks are now rated AA+/Aa1 by S&P/Moody’s. Thus Moody’s downgrade hit not only $23 trillion of US Treasury debt held outside the Fed but also $9 trillion of government sponsored debt outstanding. In short, the most consequential downgrade ever for the global bond market would have ramified even more broadly had Moody’s lowered the US country credit ceiling.

The next column in this series will confront the cocktail napkin theory sketched in this column with the facts. It will then highlight the role that the rating agencies assign to the dollar’s reserve role in their assessments of the US Treasury’s credit. The third column turns to market prices before laying out possible interpretations and sounding a warning.

Author’s note: Thanks to Claudio Borio and Frank Packer for discussion.

See original post for references

Bob’s your Uncle Sam

I am curious to know what his definition of “entitlement spending” is.

SpaceX? The Pentagon’s military contractors? Palentir? What exactly?