In October of 2025, the RAND Corporation published a report titled “Stabilizing the U.S.–China Rivalry“. Within weeks, the study disappeared from RAND’s website. No explanation. No revision notice. No reupload. For a prominent think tank, whose research pipeline is structured to avoid public missteps, withdrawal of a report is uncommon, and silence more so. The unusual disappearance of this report raises questions about internal disagreement within U.S. strategy-making circles.

RAND headquarters

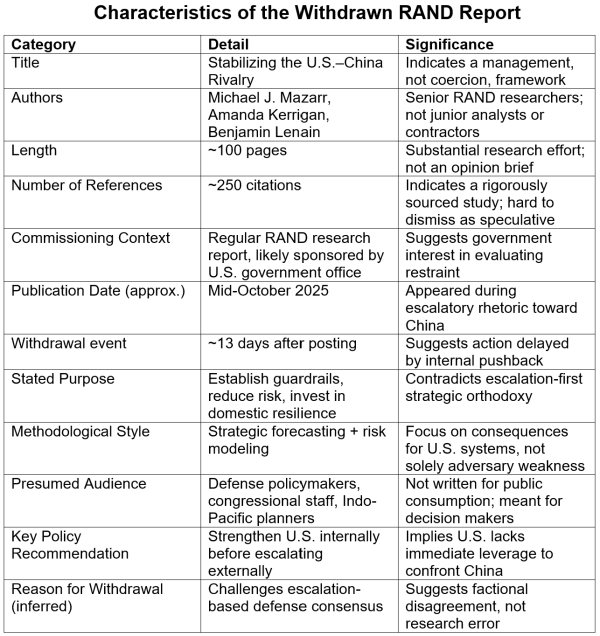

The timeline itself suggests a struggle. The study appeared on RAND’s website in mid-October 2025 and was not removed until nearly two weeks later. This is far too slow for a routine correction and far too fast for a scheduled revision. Such a delay is characteristic of an internal contest: the report was vetted, approved, published, and allowed to circulate — until opposition within the policy structure hardened sufficiently to demand its removal. The RAND report was not suppressed because it was mistaken, but because its implications became intolerable after they were recognized. The structural characteristics of the withdrawn report are shown below.

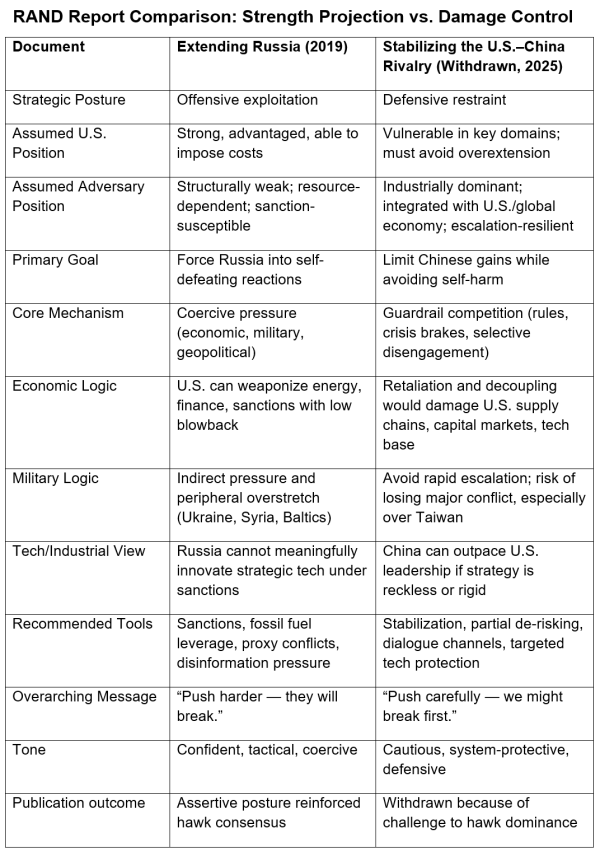

To understand why this document was retracted, it is useful to examine it alongside another historically important RAND study: “Extending Russia: Competing from Advantageous Ground” (2019). The contrast between the two offers a rare, unfiltered glimpse into an evolving, and contested, U.S. strategic worldview.

Russia as a Target of Pressure

“Extending Russia” was explicitly about Washington’s ability to impose costs on Moscow. The study recommended strategies to “extend” Russian vulnerabilities—essentially stressing the state until it faces difficult internal trade-offs. Tools included:

- energy leverage

- financial sanctions

- information pressure

- peripheral military competition.

The underlying assumption was straightforward: the U.S. possesses structural power, Russia does not. As a result, coercive measures appear low-risk and high-return. The report offers a plan for managing an adversary from a position of strategic confidence. Some foreign policy analysts have considered this report to be a blueprint for the assertive U.S. posture that preceded the Ukraine war.

China Policy as Management of Systemic Constraint

By contrast, “Stabilizing the U.S.–China Rivalry” adopts a cautionary tone unusual in U.S. strategic literature. Rather than identifying Chinese weaknesses to exploit, its central concern is avoiding actions that might weaken the United States itself. Where the Russia report encourages escalation to impose costs, the China study warns that escalation may produce asymmetric blowback affecting:

- Global supply chains

- Industrial capacity

- Technology platforms

- Capital markets

In short, costs cannot be imposed on China without risking significant retaliatory actions against the U.S. economy and defense base. (This was demonstrated recently when China responded to increased U.S. import tariffs by restricting the export of essential rare-earth materials.) The study’s recommendations center on restraint, crisis-management channels, selective “de-risking,” and internal capability rebuilding. This contrasts markedly with the confrontational approach presented in the “Extending Russia” report, and this strategic shift was likely seen as a direct challenge by Washington’s China hawks.

Why the RAND Report Withdrawal Matters

RAND reports do not pass easily into public view. Prior to publication they undergo internal peer review; methodological review; sponsor liaison and approval; and editorial and classification screening. A report cleared through these steps represents a professionally accepted line of analysis, not a personal opinion. When such a document is withdrawn after clearance, the likely cause is not faulty research, but political pressure.

The China report’s framing challenged the prevailing policy assumptions of the China hawks. U.S. defense contractors, naval lobbying circles, and military planners benefit from a narrative of unrestrained U.S. capability and open-ended escalation. A report suggesting that U.S. power is limited, particularly vis-à-vis a peer industrial economy, undermines the logic of increasing defense appropriations and escalation-oriented military planning. In other words, the report’s realism made it politically untimely.

A Strategic Debate, Not a Conspiracy

The withdrawal of the report should not be read as an incident of simple censorship. It signals something more important: a deepening institutional debate over how to position the United States in a geopolitical environment where the coercive instruments that were applied against Russia may be counterproductive against China. The China study represents a realist faction arguing that the U.S. must invest in industrial, technological, and financial resilience before pursuing aggressive competition. Its warning is less about China’s strength than America’s vulnerabilities. These include dependency on foreign manufacturing inputs; exposure to retaliatory capital controls; eroding technological monopolies; and fragile defense supply chains. The report stated the politically inconvenient truth: policy must converge with economic arithmetic.

Report Withdrawal as a Setback for the China Hawks

The quiet removal of “Stabilizing the U.S.–China Rivalry” did not simply protect a policy consensus; it exposed its fragility. The hawkish approach to China—based on the assumption that escalation will successfully impose coercive leverage—now faces practical constraints that are increasingly difficult to deny. The RAND report’s realism was unacceptable not because it was provocative, but because it was evidence-based at a moment when the dominant position is ideological.

For China hawks, escalation is a tool for restoring deterrence through fear. Yet “Stabilizing the Rivalry” presented a scenario in which escalation erodes deterrence by exposing American vulnerabilities. In that framework, the China hawk position begins to resemble what economists call a moral hazard: an actor takes on greater risk because it expects another party—here the broader U.S. economy—to absorb the costs.

This tension reveals why a defensive strategy is politically unwelcome. It requires acknowledging that the United States cannot “manage” China primarily through military signaling, sanctions, export controls, or alliance pressure. Those instruments still matter, but in the RAND analysis they function as supplements to industrial and technological renewal, not as substitutes. The hawkish model reverses that order by treating industrial weakness as an incidental issue rather than a key problem to solve.

In practical terms, the RAND report withdrawal signals a deteriorating political position for China hawks, not because their agenda lacks influence, but because its strategic justification is becoming harder to defend without suppressing research that contradicts it. The inability to allow a vetted, internally approved study from a prominent think tank to remain public demonstrates the growing incongruity between hawkish anti-China sentiment and economic constraints on China policy.

Conclusion

If the U.S. continues to debate China policy without confronting its industrial dependencies, the disagreement will not be between hawks and realists but between narrative and arithmetic. RAND’s withdrawn report was not an ideological provocation but a forecasting exercise arriving at a forbidden conclusion: the U.S. cannot pursue hegemonic competition without first rebuilding its economic capacity to compete. Refusing to say so does not reduce the cost of escalation with China. It only postpones the reckoning.

Great catch on the disappeared Rand article about China from Mr. Hovaness. Thanks for providing this article.

Yes, it sure seems that political pressure was at play, and the facts don’t fit with the bipartisan political story-line.

The “Extending Russia” article appears to have been revised since it was first posted, and a disclaimer placed above it to point out that the article is misrepresented and used for Russian “firehose of falsehood’ approach to propaganda”. The hypocrisy runs deep and wide as usual.

The warmongers don’t really care about facts, it seems they only care about their financial interests. Since political bribery has been legalized, formalized and normalized, we can expect more of the same. I would say years of institutional corruption has produced a dysfunctional MICIMATT or MIC. Over-priced and substandard weapons and hardware, in insufficient quantity underlines the problem. The trend continues until the empire is no longer able to project power abroad, that is if rational heads prevail. The greed and power-drunk oligarchy appears to have gone mad.

I had read about the report when it was published, and how commentators noted that RAND was advising a change of approach wrt China, but I was not aware that the report had been “cancelled”. Good sleuthing and excellent analysis!

The epiphenomenon of the RAND publication woes does indeed indicate that there must be furious internal disputes within the governmental machine. It confirms what Yves and especially Aurelien had been pointing at for a while: those factions defend diverging interests and have incompatible concepts as to how to proceed, resulting in seemingly inconsistent and sometimes even haphazard proclamations and policies.

It brings forward the reckoning, more like.

Excellent work, however.

A conflict between narrative and arithmetic. Wonderful!

Something tells me that it might have been Rubio and his backers that had this report yanked. Hard to sell going after China when you have that RAND report saying not so fast now and maybe we aught to think about it. Be funny if the Chinese hosted this RAND report on one of their own government websites.

Very persuasive and well presented, kudos and thanks. An old friend was a career-long (30+ years) analyst at RAND who I’d love to have read this writeup for their sense of things, not so much geopolitically (though they’d tell me anyway) as around whether, and how frequently, major studies were squashed outright due to ‘stakeholder’ pressures or, like this one, published with all approvals then withdrawn.

Having been approved after, i guess, extensive reviews this sounds very much as “someone” feeling pissed off enough to call it for withdrawal. This someone probably very, very close to the White House. Here Hovaness with his “disagreement between narrative and arithmetic” scores a nice goal. Excellent!

Excellent contribution. Thank you.

“…coercive instruments that were applied against Russia may be counterproductive against China”

Maybe those instruments are only actually useful/effective against US institutions of higher learning -?

re: a deepening institutional debate over how to position the United States in a geopolitical environment where the coercive instruments that were applied against Russia may be counterproductive against China.”

A discussion way above the pay-grade of this old infantryman, but I have to ask: were these coercive instruments effective against Russia?

We learned today that Russia is now a bigger economic player Oceana than Australia for the first time at fifth place so I don’t think so. The Euros are smugly congratulating themselves on walling off Russia from themselves and it hasn’t sunk in yet that they’ve walled siloed themselves off from everywhere.

The question was “were these coercive instruments effective against Russia?” but you didn’t provide a direct answer.

The current state of the USA=instigated strategic debacle in Ukraine provides that answer.

Thank you for this post, Haig

Agreed. Russia’s defeat of the US and NATO-led Project Ukraine hasn’t sunk in yet. Continuing the war will further strain and weaken the West, but having to admit defeat and accept Russia’s terms is (so far) a bridge too far for its supporters in the EU and in Washington. Trump cannot square this circle, much as he’d like. Reaching a deal of any sort with the Russkies is an impeachable offense for the War Party in Congress. The Empire in Decline sees enemies everywhere it looks that it can blame for its decline.The arithmetic, as Haig notes above, says something else of course: our own elites did it to us.

The Nihilists among our foreign policy elites can only hope for a Black Swan event that may defeat Russia. In reality, the more likely Black Swan event may be a nuclear one delivered by the Samsonite Zionists. It would be a final middle finger gesture of defiance to all after yet another Iran attack again brings a truly devastating response. (according to John Kiriakou, the Zionists threatened to use nukes on Iran last time if Trump didn’t bomb Iran). Mike Huckabee, Pastor Hagee, and other Christian Zionists must be rapturous at the possibility.

The Europeans are a quixotic mixture of the most obvious self-defeating follies of Fawlty Towers, the Goon Show and Monty Python mixed into a script by Kit Marlowe designed to elicit tragic sighs instead of laughter. And the only way to change Europe is to change the politicions and eliminate the governance structures of the EU.

very well written

I see why Yves added you to the team

It also meant raising money for and investing in way more than data centers.

Agree that this is a loss overall for the China Hawks. Itra-elite struggles over the narrative, so important to the symbol manipulators. When you’re forcing down accurate assessments that few people will ever read, you’re certainly not winning. Rev Kev is right about the Chinese definitely noticing it.

Link to archived PDF

https://crystalbook.ru/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/RAND_RRA3141-2.pdf

Another link, from MoA, just in case…

https://drive.google.com/file/d/11Tpjvgjrr4ZmPKusfpEdmulp-PDCbNHY/view