Yves here. I have to confess to being such a dullard that I am not a game player. But with Wordle being so popular, I am sure it is familiar to nearly all of you here and enjoyed by quite a few. Rajiv Sethi discusses group performance at Wordle and by extension, other exercises of skill, with some findings that might seem counterintuitive. One is that the most popular view tends to be right…unless it isn’t, as in a bubble.

Famed quant trader Cliff Asness says he believes the correctness of crowds, as reflected in market prices, has gotten worse over the past few decades, and does not seem to have a theory as to why. I have one. The business community has gotten way better at propaganda and spin. I’ve told the story before of how a Wall Street Journal reporter went to Shanghai circa 1993 to open the office there. He came back to the US in 1999 and was surprised to see how much business journalism had changed. The first was the uptake of the internet had almost ended normal publishing deadlines tied to when the daily issue had to be put to bed so as to go to the printer. The result was that news cycles had contracted, making it almost impossible to get to the bottom of a story before it had to be published. Second was that companies had gotten much better at spin, again making it harder to be sure about information. So the baseline of knowledge has eroded, leading to less well informed views generally.

By Rajiv Sethi, Professor of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University; External Professor, Santa Fe Institute. Originally published at Imperfect Information

I’m hoping that this post will have something useful to say about strategic diversity, meritocratic selection, and asset price bubbles. But before I get there I need to take a detour through Wordle, the popular online game that is played by over a million people every day.

The New York Times acquired the puzzle from its developer in 2022, and has added a couple of features that are generating some interesting data. Each participant can evaluate their performance relative to an algorithm (the wordlebot) that is engineered to minimize the expected number of steps to completion. The bot typically finds the solution in three or four steps and rates each player’s entry at each stage based on skill and luck. These scores range from zero to 99, and while a few players beat the bot every day thanks to greater luck, the best that they can do on skill is to match the bot.

As far as I can see, no individual player can consistently solve the puzzle faster than the bot over a long stretch. However, I will argue below that a large, randomly selectedgroup from the global population of players, working independently and then voting on the solution, can beat the bot on almost every occasion. I was initially surprised to see this pattern and attributed it to widespread cheating, but the scale of cheating is much too small to account for the effect. Something far more interesting is going on.

As an example, consider the sequence of entries chosen by the bot on November 26:

Notice that the second word here is ruled out by the feedback on the first. This is a common strategy for the bot—restricting oneself only to words that remain feasible at every stage is not optimal, if the goal is to minimize the expected number of steps required.

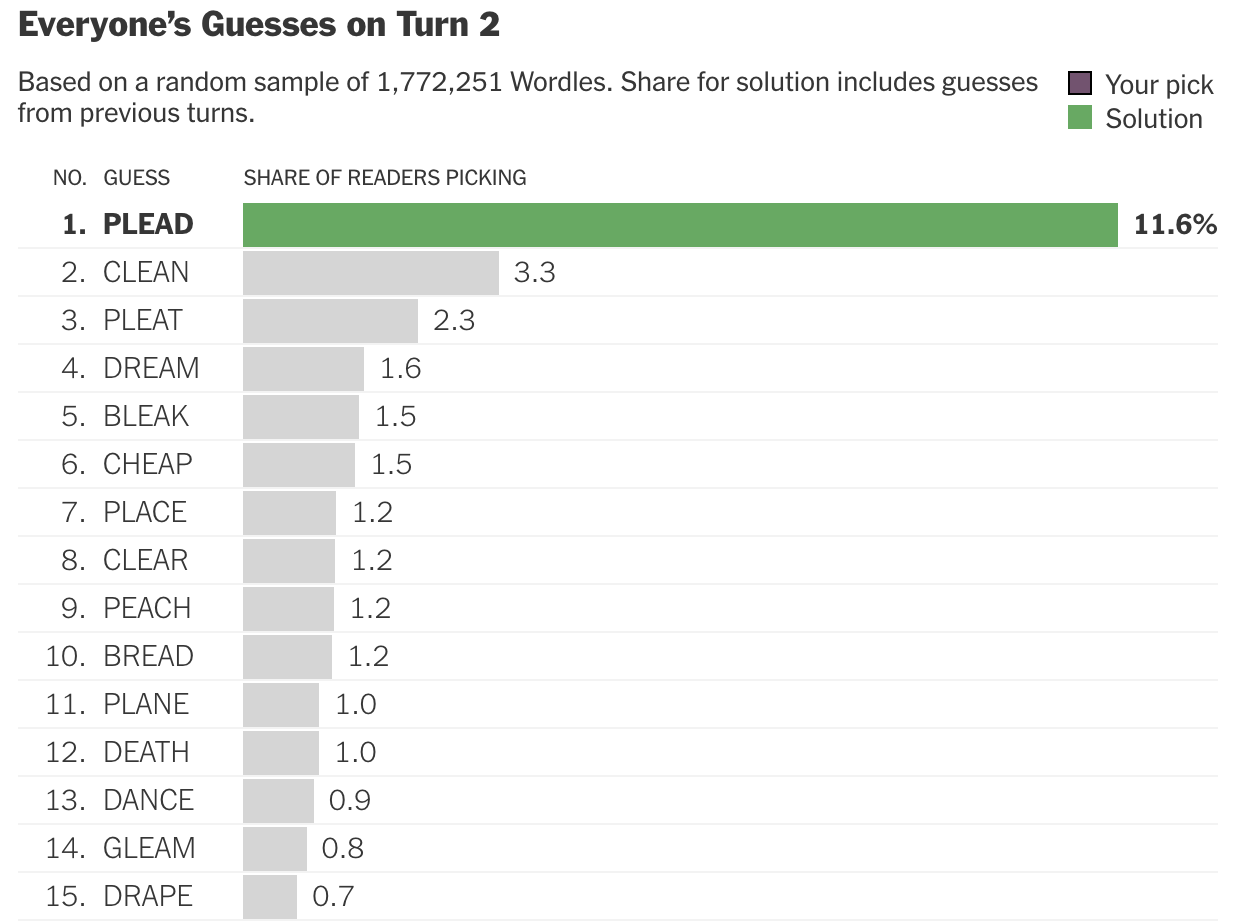

Most human players don’t act in this way. At each stage, they tend to choose a word that has not yet been eliminated, and this gives rise to a striking effect. Here are the choices made with highest frequency at the second stage for the November 26 puzzle, based on about 1.8 million entries:

Notice that the word chosen with highest frequency is in fact the solution. If a large, randomly selected subset of players from the participant pool were to submit their choices at each stage to an aggregator, and the latter simply picked the highest frequency word as the choice of the crowd, the crowd would have beaten the bot on this particular day.

But not just on this day. Based on data over the past few weeks (starting on November 1), the crowd never took more steps than the bot, and took strictly fewer steps on 85 percent of occasions. The bot on average took 3.5 steps to solve the puzzle while the crowd on average took 2.4 steps. On more than a quarter of occasions, the crowd found the solution in two steps while the bot took four.

When I first noticed this pattern, I felt sure it must be due to widespread cheating. Perhaps players were making multiple attempts using different browsers or devices, receiving hints from others, or simply looking up the solutions before entering them. There is certainly some evidence for cheating—about 0.4 percent of players find the solution on the first attempt, which is about twice the rate that would be expected by chance alone. But if the amount of cheating were substantial, then the average “luck” score for the crowd would be much greater than that for the bot, and this is simply not the case. For example, over the past couple of weeks the bot had an average luck score of 54 while that for the crowd was 56. So the scale of cheating is negligible and cannot account for the patterns in the data.

Here’s what I think is going on.

First, there is a lot of diversity in choices at the first round. The ten most popular words jointly account for just thirty percent of choices on a typical day, and there are hundreds of distinct words chosen at the first step.

Second, at subsequent stages, players tend to choose only words that remain feasible. Each player faces a set of words that have yet to be eliminated given their prior choices, and the diversity of choices at earlier stages implies that these sets vary a lot in size and composition. Furthermore, every such set must contain the actual solution, so in the union of these sets the solution must appear with highest frequency. Even if every player were to choose from among the remaining feasible words completely at random, the most likely winner at the second stage should be the actual solution.

By the third stage, I would guess that the most popular choice is almost certain to be the right one, and this is in fact what one sees in the data. Since November 1, the crowd has solved the puzzle in two steps about 60 percent of the time, and has neverrequired more than three steps.

This reasoning leads to an interesting hypothesis—a large pool of randomly drawn participants will find the solution faster than a pool of equal size that contains only the most skilled players. The latter pool will involve very little strategic diversity, with all players behaving in ways that are very similar to the bot. This hypothesis is experimentally testable. If validated, it would provide striking evidence for Scott Page’s claim that there are conditions under which cognitive diversity trumps ability. And this has implications for the manner in which we conceptualize merit—as a property of teams rather than individuals.

The success of the crowd at Wordle resembles that of the audience in the television quiz show Who Wants to be A Millionaire? A contestant who is stumped by a question can choose to poll the audience, each member of which then independently submits their best guess among the four possible answers. The most popular response has a very high success rate—as high as 95 percent for questions of low to moderate difficulty.

In a recent conversation with Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway, Cliff Asness explained why this lifeline tends to be so successful:

At least to my non-exhaustive examination, it seemed to work pretty much every time, even if the question was hard. Because imagine you have a hundred people in a room, 10 of them know the answer. The other ones are guessing. The 90 distribute evenly over the four, maybe not perfectly evenly, but roughly evenly. The 10 all land on B. So you pick B because it’s bigger. Worked pretty much every time.

There’s a crucial assumption in that. The audience has to be relatively independent of each other. And they did that. They weren’t talking. It was silent voting. If the audience all gets to talk, maybe the 10 convince the 90, but maybe they don’t. Maybe a demagogue with a better twitter feed convinces everyone. And if you ruin the independence… have we ever come up with a better vehicle for turning a wisdom of crowds into a craziness of mobs than social media? I’d be hard pressed to describe it.

The independence of choices here is vitally important—when a contestant thinks aloud before activating the lifeline, correlation in responses is induced and this can compromise accuracy. The Wordle crowd is successful in part because it is composed of millions of people scattered worldwide, most of whom are working independently.

Cliff Asness was a student of Eugene Fama at the University of Chicago, but is hardlya dogmatic adherent of the efficient markets hypothesis. In fact, he seems to believe that markets have become less efficient over the past couple of decades, and claims to have “drifted from 75-25 Gene (Fama) to 75-25 Bob (Shiller).” He is concerned, as are many others, with the possibility that we may be living through an AI bubble.

What sustains bubbles in asset markets is the difficulty of timing the crash. Even if it is widely believed that some asset is overvalued, those who bet on a decline may do so too early and be forced to liquidate their positions before they start to become profitable. This was the fate of many sellers during 1999 and early 2000, before the bubble in technology stocks finally burst. The problem is one of coordination—betting on a price decline is enormously risky and likely to fail if one does it alone. Coordination does eventually occur, but those who act too soon can end up losing their shirts.

We may or may not be in the midst of an asset price bubble, but to dismiss the arguments of Cassandras on logical grounds, as people sometimes do, would be naive in the extreme. Crowds can be wise when the stakes are small—on quiz shows and online games—but subject to extraordinary popular delusions when the stakes couldn’t be larger. This might seem paradoxical at first, but makes perfect sense if one thinks about the incentives with sufficient seriousness and care.

passive ETF investing changed the game. with so much money never selling (unless it’s quarter/year-end), one only needs to move a small, discrete segment of hot money

also passive money provides de facto limitless equity capital as passive money doesn’t care if management dilutes shareholders.

see Carvana rescuing itself, in part, because passive shareholders got diluted; and that gave CVNa the lifeline that it needed

Harper’s had an interesting article in a similar vein to your comment – https://harpers.org/archive/2024/06/what-goes-up-andrew-lipstein-401k-doomsday-index-fund-catastrophe/

Unfortunately it’s paywalled but I’m wondering if anyone else read it when it came out last year. A very general summary going by memory – the author notes all the billions of dollars going into 401Ks on a weekly basis which are then used to buy assets to track the market, rarely ever selling as you noted. He argues that this has created a gigantic bubble. It was a plausible argument, but I remember some flaws in it. I’d have to re-read it to remember the details.

I think there’s something to Sethi argument’s that the wisdom of crowds breaks down when there’s a lot more at stake, and I think Yves is correct that all the hype has distorted market results.

When I first starting investing a little bit as a teenager, I bought stocks based on watching the stock quotes in the business section of the dead tree paper, which you could only get the day after the market closed and not in real time (unless you were super connected), and by reading quarterly reports. If revenues were going up for a few quarters, and the stock price was doing OK and had a respectable P/E ratio, I would buy. I had to get on the phone and call a broker to do that. I got great returns on the first few equities I purchased, and investing seemed to work the way it was supposed to.

Things changed once they turned on the interwebs. Suddenly there were online brokerages everywhere, and investment websites with their various opinions proliferated. One big lesson for me came from one of the more cautious and respectable investment websites in the late 90s – if i remember right it was called Individual Investor. They wanted to show how all the hype was affecting the stock markets, causing massive volatility based on nothing but vapor. They picked a stock called BIKR, which was a tiny company that had a website that sold motorcycle accessories. It traded around $1/share or so. Individual Investor hyped a strong buy rating and the stock rocketed up to above $10/share in the next day or two, before rapidly falling back to earth. Point taken. That convinced me not to buy anything with a .com in the name since it was just a glorified catalog, especially at the time, with Pets.com being the famous one most people remember.

Today you have Jim Kramer honking horns and clanging bells all day while being wrong, know-nothing punters with a million opinions at your fingertips, and hordes of HODLERs on scam sites like Robinhood (whose business model seem to be selling customer trading data so others can frontrun those customers). So these days I just put my earnings into a 401K investing in ETFs and hope for the best at the casino. Because it really doesn’t feel like investing anymore and a lot more like rolling the dice.

I quit Wordle when they started curating it

A number of friends are really into Wordle, but i’d rather torture the words so that they’ll say anything…

Gustave Le Bon’s 1896 masterpiece is one hellova read, and human nature doesn’t change much, check it out~

The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind

Think of that bullshity trucker story yesterday with AI trickery~

I don’t think the AI image helped their cause but Highway Angels seems to be a thing.

https://highwayangel.org/

A better example would be Bitcoin…

Every story I read in regards to it, displays a photo of a metallic coin because you can’t sell invisible air, there has to be something to it.

If you’d like one of the metal Bitcoins, they are a few bucks on eBay.

huh. i’ve generally operated under the null hypothesis that cognitive diversity trumps ability in the vast majority of cases. my reasoning is the identification of ability begs the question, and that our society is not good at that. but this is a interesting different take

One thing about spinning is that it requires certain preconceptions on the part of the people being spun. Cognitively diverse crowds will be more difficult to spin, at least not with the same shtick, as they will start from different premises. So there is a potential linkage between how easily bubbles can form and be maintained vs the nature of the crowd.

Asness said on the Odd Lots podcast that the success of the wisdom of crowds depends on the independence of each actor and that he thinks social media is undermining independence (and thus the wisdom of crowds)

“As far as I can see, no individual player can consistently solve the puzzle faster than the bot over a long stretch.”

I’d surmise that an individual player almost definitely can (and I wouldn’t rule out that I myself might, although I haven’t really checked).

The most obvious thing, mentioned in the post, is that a player knows (or can know), what the previous solutions have been and can exclude them from consideration. The bot has “solutions amnesia” and can’t exclude them. That means the bot (1) is guessing from a pool of solutions that might be larger than the actual current solution set but, more importantly, (2) is making strategic guesses that are optimized for all the solutions and are likely suboptimized for the actual solutions at play. (The bot often tells me that some guess would be “more efficient” than the guess I made, when it clearly is not, for the actual solutions left, because, again the bot is accounting for solutions that are no longer at play.)

The other thing is the bot doesn’t know the words in even the initial solution set but is picking solutions from a somewhat larger set that the bot “considers plausible solutions.” But the bot comes up with some pretty implausible words as solutions, e.g., ABOIL, PEATY, neither of which are in the actual solution set. Such words might not even occur to most players, which would actually be an advantage in the long run. Ignorance really is bliss—sometimes.

All this adds up to the possibility of individual players having a distinct advantage over the bot. (I realize that the performance of individual players vis-à-vis the Wordle bot is not the point of the post—but since it was mentioned, I thought I give my 2¢.)