Today, the Financial Times has a prominent article on how the giant public pension fund and private equity investing heavyweight CalPERS has a new push on to reduce the fees that it pays to private equity firms.

This would all be salutary, except that a board meeting in December exposed that CalPERS’s staff has an unduly narrow conceptualization of the charges that private equity firms are taking out of the companies that they buy with the funds of limited partners like CalPERS. That means that their efforts to reduce fees will be substantially, and potentially entirely offset by fees charged directly to portfolio companies directly. That money comes every bit as much out of limited partners’ pockets as fees paid directly, since it reduces the profits and cash flow of investee companies, impacting their financial performance and the price paid for them when they are sold.

The narrow focus on fees also has the potential to distort private equity general partners’ incentives even further by making even more of their compensation come out of riskless charges (management fees and fees and expense charged to portfolios companies) and less out of performance fees that depend on the general partner picking winners.

We’ll start with a short primer on how the fees, and more important, the so-called fee offsets work. If you are familiar with that, you can skip to the second bold subhead to get to the noteworthy disconnect between CalPERS’ media claims about its fee reduction efforts and what came out at the December board meeting.

Private Equity Fees and Fee Offsets

When the public hears about private equity and hedge fund fees, they assume they consist of the prototypical 2% annual management fee and a 20% participation in profits, which is generally called the carry fee. In private equity, there are some additional complexities even at this level. The 2% fee is generally lowered in the later years of a fund; the 20% carried interest is typically subject to first meeting a hurdle rate of a 6% to 8% return.

There is actually a good deal more artwork, but two additional issues are germane for our discussion today. The first is that most general partners also charge fees directly to portfolio companies for services they supposedly provide. And we do mean “supposedly”. One fee, for instance, is a so-called monitoring fee that is a charged for management services allegedly provided to portfolio companies. Oxford professor Ludovic Phalippou, who has reviewed the actual agreements which the general partners impose on the portfolio companies, described these fees as “money for nothing“.

Now it is critical to remember: investors like CalPERS have absolutely no idea of how much money the general partners are taking directly out of the portfolio companies. Those payments go directly from the company to the general partner or one of its affiliates, and do not flow though the limited partnership. The investors have no right to see the books and records of the portfolio companies and are blind to what is going on.

Now instead of doing the sensible thing and saying, “Get rid of these portfolio company fees or we won’t invest,” limited partners agreed to a fix that of course works in the general partners’ favor. The fees charged to portfolio companies are partially (or in the case of limited partners like CalPERS, fully) rebated against the management fee. A typical percentage of fee rebate, or “offset” in industry nomenclature, is 80%.

So why is this not a great solution? The limited partners have no audit rights; they don’t even get detailed explanations of why the management fee reductions claimed are what they are. So the general partners can cheat on whether the funds they take out of portfolio companies are actually being offset in the manner that they think they are. A Wall Street Journal expose on KKR affiliate Capstone shows how KKR took payments from portfolio companies and paid them to an in-house consulting firm without sharing them with limited partners.

Another reason this remedy favors the general partners is that the amount of rebate is limited to the total amount of the management fee. That means that if the offset amount exceeds the annual management fee, the general partner keeps the excess. Not only can that happen in the early years of the fund, it is more likely to happen in the later years of the fund when the management fee level falls.

The second issue that is germane for the CalPERS discussion is how the carry fee is actually computed. Contrary to what a sensible business person might anticipate, it is generally not based on total fund performance, but is calculated and extracted paid on each and every deal sold. Since the best-performing deals are usually sold early in a fund’s life, it’s common for carried interest fees actually paid to exceed what in theory was actually due and owing when the fund is finally wound up, since early stars are offset by later dogs. But the so-called clawback language that is supposed to remedy that problem is actually constructed not to work well in practice. Moreover, in those rare instances when the general partner really can’t deny that it owes money despite the tax escape hatches it put in its clawback language, they usually manage to negotiate their way out of coughing up any cash.

CalPERS’ Claims About Its Fee Reduction Push

Let’s look at what CalPERS says it is doing to reduce private equity fee extraction. From today’s Financial Times:

Calpers, the largest US pension fund, is slashing the number of private equity managers it uses and teaming up with other investors to drive down fees, as it extends a review of alternative investments that has already resulted in it pulling out of hedge funds entirely…

Ted Eliopoulos, Calpers chief investment officer, told the Financial Times that it would use “every possible lever” to drive down costs, as US pension funds intensify the debate about whether private equity groups justify the large management and performance fees they charge.

Calpers, or the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, said it was hoping to cut the number of private equity managers it used by more than two-thirds, to 120 or fewer, and Mr Eliopoulos suggested the final number could fall below 100.

“By having fewer managers, at larger scale, we will be able to reduce our overall costs,” he said. “We are looking at every possible lever to use to lessen the cost but make sure we still have access to the talent that we need.”

The pension fund is also looking for other investors to team up with on certain investment strategies. Its aim is to negotiate better deals from private equity managers, Mr Eliopoulos said. “By working with like-minded partners, we also believe we will be able to reduce our costs over time.”

However, there is a lot less here than the bold talk would have you believe.

But Does CalPERS Even Understand Its True Costs?

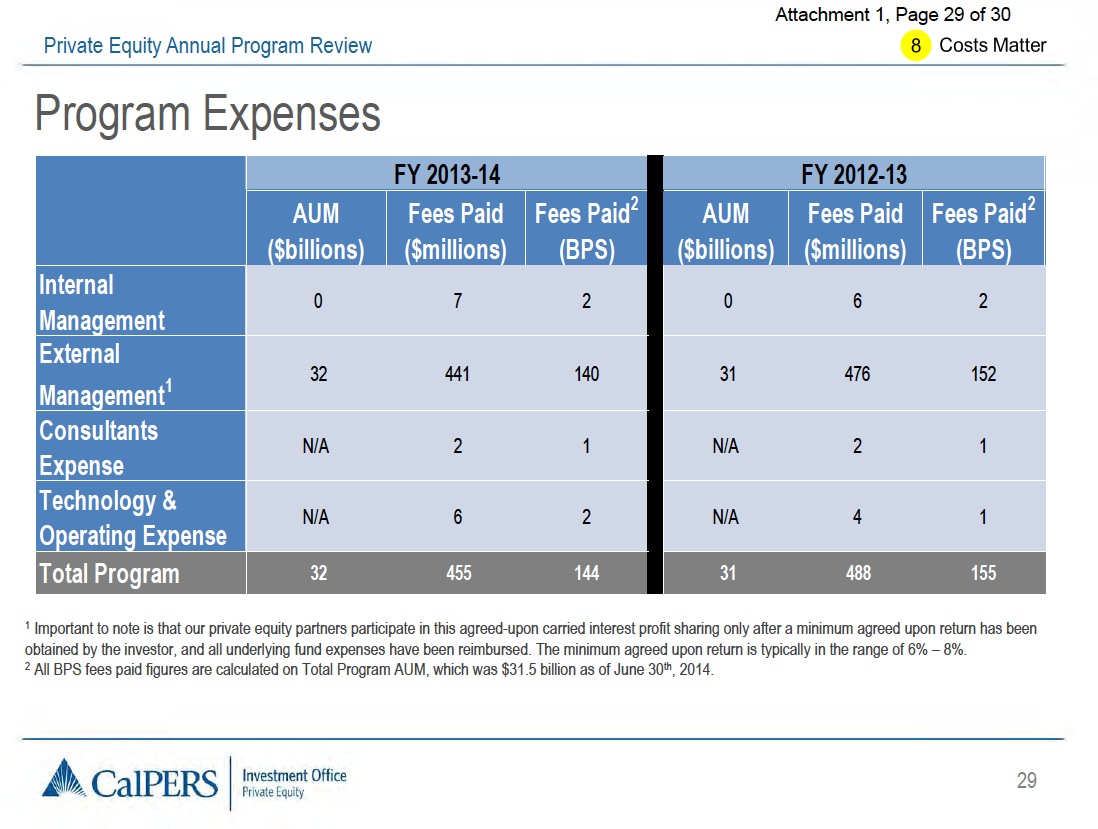

Let’s see how a recent board meeting revealed how embarrassingly superficial a view CalPERS’ staff has of its actual costs. This slide on p. 29 is from a December 14 presentation to the board.

If you read the slide, you’d think CalPERS is doing a good job of containing fees, since its external fees paid in 2013-2014 were $441 million, down from $476 million in 2012-2013. But as soon as you pull out a calculator, you know something is wrong with the numbers. CalPERS’ average funds under management over that year were $31.9 billion. $441 million is 1.38% percent of that total. That clearly does not include carry fees, as footnote 1 might lead you to believe. It also looks way too low to include the fees paid by the portfolio companies that are offset against those fees. Those fees reduce the value of CalPERS’ investment and are thus every bit as much real costs as the more obvious actual cash outlays that they make.

This exchange between the new head of private equity, Réal Desrochers, and board member JJ Jelincic, confirms the worst fears one has about what that slide says about how naively CalPERS thinks about the charges its managers are making against the funds it invests. The discussion starts at 1:26:20:

So let’s see what we learned:

1. Desrochers confirms that the slide only covered management fees and therefore ignores the whole cost. He offers to discuss carry fees in closed session, meaning privately. Why is this not a matter of public disclosure like the management fees paid out?

2. Derochers frighteningly does not seem to appreciate that even if the fee offsets worked the way the limited partners naively assumed they do, that the effect would be that they would still be bearing the cost of the full management fee. Notice his statement at 1:30:15 that “I don’t know how many years where the LP did didn’t have to pay any fee because they were charging to the company. And they were reimbursing the management fee.” This is classic drunk under the streetlight thinking of focusing on what is visible as opposed to what is relevant. It’s just that some of it is paid in hard dollars and some in charges to their investee companies. As Jelincic points out, CalPERS still bears all costs of the management fee. At that point, Desrochers either relents or corrects the impression he gave earlier.

And as seems to be par for the course for the industry, Desrochers evidences no concern that limited partners get ONLY a share of fees specifically enumerated in the limited partnership agreement, and that the fee rebates top out at the amount of the management fee actually paid.

Why does this matter? It undermines the CalPERS push to reduce fees in isolation. It’s reminiscent of the person who thinks they are on a really stringent diet because they’ve cut out a lot of fat while ignoring that they are winding up eating more food to feel satiated, and hence not anywhere near as far ahead as they think they are.

The more that CalPERS drives the management fee down, the greater the odds that that effort will be vitiated by the fact that the portfolio company level fees will exceed that, meaning all those efforts to get a better break were largely for naught.

And it’s not such a hot idea to push to lower carry fees in the absence of insisting on getting full transparency on the fees and expenses pulled out by general partners on the portfolio company level, and negotiating to reduce the total amount extracted from investors. CalPERS in a recent CFO conference said that it was averaging a 10% carry fee. It’s not clear how much of that is due to the impact of the hurdle rate versus negotiating for a lower carry percentage. As Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt pointed out in their important book Private Equity at Work, 2/3 of the compensation to the large private equity firms comes from fees that the firms get independent of how the deals do, which creates incentives to do deals just to get fees, as opposed to make money for their investors.

Problems with the CalPERS’ Plan to Reduce the Number of Private Equity Managers

CalPERS’ other big push, to reduce the number of private equity managers, isn’t all it is cracked up to be either. Given how large CalPERS’ program is, the net result will be for the public pension fund to considerably increase its investments with the largest funds, such as Apollo, Blackstone, KKR, TPG, and Carlyle. The SEC has indicated in its private equity fund examinations that it is seeing the worst abuses at some of the largest funds. It would behoove CalPERS to get to the bottom of what amounts to embezzlement before it hands more money over to them.

Moreover, odds favor CalPERS not meeting its objectives, for good reasons and bad. It’s common for limited partners to aspire to have a more concentrated portfolio and never manage to get there. First, making real progress means selling out of current funds. That is not a fun process and typically entails recognizing losses. It’s way too easy to sign up new managers, particularly when some have most favored nation status by representing a minority group, or having powerful political connections. And a manager who is supposedly not on the preferred list may have a particularly appealing focus or genuinely appear to be best in class. So initiatives like CalPERS’, like all too many New Year resolutions, tend to fall by the wayside.

At a higher level, this exchange yet again demonstrates how badly captured the limited partners are. They passively accept the parameters set by the general partners and ask for concessions only within that framework, rather than demanding entirely new arrangements in light of well-publicized abuses and gaping shortcomings in transparency and accountability.

One of the biggest mysteries in the world is why these pension funds invest in this PE stuff. No liquidity, little transparency, opaque valuation, lackluster performance, high fees.

Sounds like a great investment.

It’s the feeling of importance, of playing with the big boys, that keeps them around. Nothing more or less than that, is my read.

Wonder if it’s just a case of CalPERS thinking being 30 years out of date — i.e. thinking there are laws, SEC seriously enforces the laws, investment companies wouldn’t behave badly out of reputational concerns and fear of the SEC — or if there are private considerations on the CalPERS board. Your posts should clear up CalPERS thinking on the first possibility.

Thanks for these PE posts. It’s something I don’t understand so I read NC to learn.

Institutional corruption is a problem, but it goes hand in hand with institutional not giving a shit. People let things continue as they are because they won’t get yelled at for doing the same old shit, even if it’s horrible in every direction. It seems like they’re in serious need of new blood.

Fees charged to portfolio companies actually cost the Limited Partners a lot more than they appear. A $1000 fee charged to the fund costs the LPs $1000. A $1000 fee charged to the portfolio company reduces the portfolio company’s EBITDA by $1000, which translates to $8000 in purchase price if the company is sold for 8x EBITDA. If the LPs keep 80% of the gains, the $1000 fee reduces their take by $6400.

In theory, you are correct, but in practice, that is not how it works.

When portfolio companies are sold, the financials are adjusted to back out the charges made by general partners that cease at closing. So there’s no EBITDA reduction due to those charges that would impact the sale price, save for fees that continue post sale. And there have been stories about fees like that, see

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2014/05/new-york-times-new-editor-buries-important-story-private-equity-fee-shenanigans-holiday-weekend.html

Are there no model plain English limited partnership agreements for the pensioner to look at? Something with a clear statement of principles that every agreement should include. Pensioners should be able to ask a simple question: does our agreement include a, b, c, d …? And, if not,

why not?

.

Surely you jest. See our post and our documents trove:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2014/05/private-equity-limited-partnership-agreement-release-industrys-snowden-moment.html

The private equity industry has gone to extreme lengths to keep these documents secret. They have gotten either legislation passed or favorable state attorney general opinions in every state to prevent them as well as other important documents and information from being subject to public disclosure.

And the documents are created by the general partners, since they are agreements to invest in their funds. They have the best legal talent in the county working for them. There is a fiction that the limited partners can negotiate these deals, but no one limited partner is important enough to have that kind of clout, plus they can’t even get good representation:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/07/memo-to-eliot-spitzer-if-harvards-own-pe-law-firm-is-really-more-loyal-to-bain-how-can-you-hope-to-get-good-representation.html

The law firms make vastly more money working for general partners than they ever will for investors.

This story invites the question, of who will replace Kamala Harris if she takes the senate seat?

We know Jamie Dimon was able to stifle CA prosecutions with hush money, and voila, Harris “graduates.”