Yves here. In fairness, the original title of this VoxEU post is “European integration and populism: Addressing Dahrendorf’s quandary,” but I think you’ll find my relabeling it to be fair.

I’m posting it because I was struck by the way the authors mischaracterized the populist upsurge, and the worst is, my sense this reflects a lack of comprehension and/or a refusal to believe that the adherents are well-informed about their own circumstances. This appears to reflect the yawning gap between the members of the elite, their technocratic aides and administrators, and the large swathes of the public that have suffered as a result of neoliberalism. In particular, it treats the opposition to the TPP, TTIP, and TISA as being a revolt against trade. Huh? In Europe with the TTIP, even more so that in the US with the TPP, the objection to the TTIP was mainly about the investor-state dispute settlement process, which would gut environmental, product safety, and labor regulations, and on the EU’s ability to maintain strict privacy regulations.

And this is just dishonest:

But populists do not talk in terms of disagreement over policy, which in a democracy is the very point of politics; rather they claim that they and they alone speak in the name of what they tend to call the ‘real people’ as opposed to the ‘establishment’

Sanders was and is all about policy. Mark Blyth pointed out that the reason Marine Le Pen might win despite the odds in the second round of the French presidential election is by virtue of her economic positions:

…if you actually go to their website and look at their economic policies, I find it much more progressive than anything else that’s on offer and the mainstream French left have completely collapsed…What’s meant to happen is that the entirety of the French left voting public is meant to get behind their equivalent of Mrs. Thatcher who thinks that what France needs is a healthy dose of more markets and austerity to get things going again. And to vote for that person to stop the Front. Now on every issue apart from immigration, you actually agree with the Front’s policies. And you disagree with everything this guy’s got except immigration. That has, “I’m not going to show up” written all over it. And that’s how the National Front gets in.

Even Trump talked about policy. He just took so many and not always consistent policy positions it wan’t clear what you were buying in voting for him. But Clinton made it very clear it was Not Her and not the status quo, and that turned out to be enough for a lot of people.

And the big reason for the authors’ having troubling wrapping their minds about populism, in that they actually manage to acknowledge that the EU/Eurozone projects haven’t worked out to the advantage of many citizens, seems to be that they have deeply internalized neoliberal dogma: they believe that countries must stay competitive, even while admitting that that inflicts costs on their populations. Japan has effectively renounced that tradeoff, preferring social cohesion to groaf. Japan still leads the world in virtually every social indicator, such as longevity (still more than four years longer than the US), low crime rates, educational attainment, despite having to deal with a financial bust bigger that ours and stagnant GDP per capita, which means it has fallen in relative terms. Pray tell, who has really made the better choice? And let us not forget that Japan has been contending with a bona fide borderline depression for nearly 20 years longer than the US has been struggling with its “new normal”. (For a longer-form debunking, see How Pursuing “Competitiveness” Crushes Labor and Lowers Growth, “The Notion of the Competitiveness of Countries is Nonsense”, and How the Labor Cost Competitiveness Myth is Making the Eurozone Crisis Worse).

Finally, notice how the article recommends coming up with a better “narrative” rather than policies that provide tangible material benefits to middle and lower middle class citizens. In fairness, if you read through their recommendations, some of their overly wonky suggestions are intended to address needs of EU citizens. But the weird combination of overly-abstract, alienating language and the emphasis on “narrative.” Even with presumably good intentions, this sounds far too much like Obama’s approach of believing that every problem could be solved with better PR. Why should a failed strategy that helped usher in Trump be seen as a remedy?

By Marco Buti, Director General, DG Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission and Karl Pichelmann, Senior Adviser, Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission. Cross posted from VoxEU

EU institutions and policy settings are prone to populist attack from both the purely economic and the more cultural ‘nativist identity’ angle. Current competences, mostly confined to organising markets and lacking the ability to address distribution effects, make the EU appear as the agent of globalisation within Europe, rather than a joint European response to globalisation. At the same time, it is charged with undermining national autonomy, identity, and control. Against that background, we set out five guiding principles for policy articulation at the EU level for a new positive EU narrative.

The Tide Has Turned

After a decades-long process where national economies became more and more entangled and interdependent at both the international and regional level, increasing strains to economic integration are evident both at the global and the European level. Examples abound – even without mentioning Brexit or the 45th US president – from rising stress in international capital and currency markets to protectionist pressures of all sorts on domestic markets coupled with a rising tide of nationalistic, actually often nativist, go-alone policy approaches. What is at stake is huge as the spectre of disintegration is raising its ugly head and, in fact, an integration process that has been the bedrock of a half-century of peace and economic development can no longer be taken for granted.

The current rise in populist parties is a wake-up call resembling what the late Ralf Dahrendorf – a major scholar of the 20th century and a former member of the European Commission – summarised a little more than 20 years ago as a quandary between globalisation (as a means towards growth), social cohesion and political freedom:

“To stay competitive in a growing world economy [the OECD countries] are obliged to adopt measures which may inflict irreparable damage on the cohesion of the respective civil societies. If they are unprepared to take these measures, they must recur to restriction of civil liberties and of political participation bearing all the hallmarks of a new authoritarianism (…) The task for the first world in the next decade is to square the circle between growth, social cohesion and political freedom” (Dahrendorf 1995).

Indeed, the EU integration process has traditionally been conceived as a means to square the circle, allowing for catching-up economic growth and convergence (the EU as a great “convergence machine”; Indermit and Raiser 2012), while preserving Europe’s social model(s) as reflected in the EU social acquis. However, while the deepening globalisation and integration process has generated overall income gains via higher static and dynamic efficiency, in combination with skill-biased technical progress, it has almost certainly not been Pareto-optimal, creating winners (take-it all) and losers in an age of massive transformation. The financial crisis and its fall-out have only fuelled an already existing undercurrent of discontent and fading trust in democratic institutions and the so-called ‘elites’ to deal with the (real or imagined) unfair distribution of gains and burdens in society. In this context, EU institutional settings and policies have been increasingly perceived as being pro-market biased, paying little attention (if any) to their social impact, and undermining cohesion, solidarity, autonomy, and governability at the national, regional, and local levels. Put succinctly, in Musgrave’s Three Functions of Government, the EU is seen as dealing with the allocative and, subordinately the stabilisation function, while not caring about the redistribution function which was largely left to member states.1

A Populist Backlash with Economic and Cultural Roots

The backlash against globalisation and integration runs deeper than cheap populism, as it is nurtured by economic and cultural roots that should not too easily be dismissed.

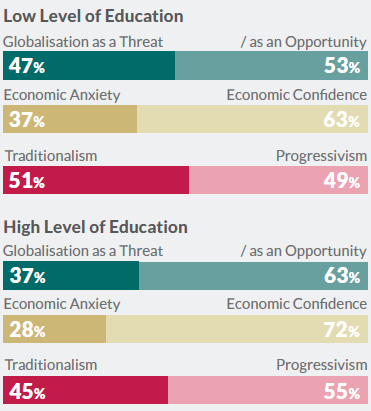

New trade agreements face fierce opposition almost everywhere. TTP, TTIP, CETA – acronyms such as these, once only known by specialists in the field, have become household names and prominent issues in election campaigns. And unfettered market opening policies have lost a lot of their appeal with a growing recognition that the rising tide has not lifted all boats; on the contrary, in some cases perhaps even only a few super-yachts. Losers in the globalisation process have become clearly visible, while the middle classes have seen scant evidence of the gains once promised. Over the past decade, political scientists and economists have amassed a considerable body of survey evidence which shows that ordinary peoples’ attitudes towards globalisation and integration are exactly what Heckscher-Ohlin economics would predict (Figure 1). Thus, while globalisation may not actually be the main culprit, there is nothing populist about noticing that the past decades have seen the top 1% grab an ever-larger share of national income and wealth – a trend particularly pronounced in the US – while median incomes have stagnated.2

Protectionism, if not to say outright hostility, already rules the day when it comes to immigration. The arrival of migrants is perceived as threat that diminishes or dilutes the locational premium enjoyed by citizens of host countries, which includes not only possible direct economic impacts on jobs and wages, but also good health and education services, and public goods like the preservation of national culture and language. Arguably, the fears about ‘native identity’ posed by immigrants from a different ethnic, cultural, and religious background largely dominate the public debate and are often ruthlessly exploited by populists; thus, pro-immigration arguments that it may have long-run positive economic effects tend to fall on deaf ears.

Figure 1 Working class and low-skilled people tend to see globalisation as a threat

Source: Bertelsmann Stiftung (2016)

It has to be acknowledged that some of the attack lines by populists are derived from a response to real grievances; and not everyone who criticises elites is a populist, and not everyone who worries about immigration is a racist. But populists do not talk in terms of disagreement over policy, which in a democracy is the very point of politics; rather they claim that they and they alone speak in the name of what they tend to call the ‘real people’ as opposed to the ‘establishment’ (Müller 2016). This is coupled with assurances to restore autonomy, identity, and control, which were taken away from citizens by hostile forces. The identity offer of the ‘us, the honest (native) ordinary people, versus them, the corrupt elites’ is very powerful and tempting in an era of massive transformation where, to use a term coined by Zygmunt Bauman, many people are left to lead a ‘liquid modern life’ amidst multiple insecurities threatening the social fabric.3

The populist promise to restore autonomy, identity, and control typically comes with disrespect for rules and procedures, disparaging the in-built checks and balances of representative democracy while propagating referenda and other elements of direct democracy to implement ‘the true will of the people’. In this context, ridiculing expert opinion (admittedly sometimes made all too easy) and denouncing statistical evidence as abstract and not in line with the experience of ordinary people (‘numbers are liberal’) belongs to the standard repertoire. Populists have also been quick to realise the potential of social media given their (partly real, partly imaginary) offer to create a space of common identity and understanding and to establish a direct link of identification between the individual and its alleged true authentic representative.

The EU and European Integration as an Easy Target for Populist Onslaught

The EU has become a popular ‘punch bag’, an easy target and prey. It is of little comfort that the EU is often not really the main concern of many of its critics. They use opposition to European integration as a vehicle for their ultimate objective: to strengthen their influence and power at home. But we need to acknowledge that EU institutions and policy settings are prone to populist attack from both the purely economic and the more cultural ‘nativist identity’ angle (Müller 2016).

From an economic perspective, the established policy allocation and the distribution of responsibilities between the EU institutions and the member states (Padoa Schioppa 1987) – with the central level being predominantly focused on growth and efficiency (free trade, open markets, the four freedoms, competition, etc.), while the social dimension was largely left to member states – have made ‘Brussels’ an easy scapegoat, accused of ignoring the social consequences of its policies and, even worse, undermining the capacity of the nation state to deal with them. The EU and populist forces collide as they operate in the same sphere, namely, the market, with the EU aiming at opening and integrating markets internally (Schengen, the single market, labour mobility, competition policy) and externally (trade policies), and populists aiming at closing them. In consequence, the EU is seen as the agent of globalisation, rather than the response to it.

The distributional fault lines are easily identifiable, impacting upon all three dimensions: the pre-market distribution of endowments, the distribution of gross market incomes, and the post-market distribution of net disposable incomes. Integration and open market policies affect the relative scarcities of production factors, with free (embedded) factor flows in integrated markets favouring mobile factors; they propagate (skill-biased) technical progress associated with a globalisation/digital divide, favouring capital and high-skilled labour; and they may enhance dynamic agglomeration effects, thereby increasing high/persistent regional disparities. EU policies and deeper economic and monetary integration increase competitive pressures and enforce higher market flexibility which, if left unattended, may negatively affect working conditions and protection in the market and undermine established rent-seeking and rent-sharing practices. At the same time, the room for re-distributional manoeuvre at the national and local level becomes more limited due to a reduction of discriminatory and enforcement power, enhanced system competition effects, and, last but not least, the perception of fiscal rules as a straight-jacket rather than as a safety vest. Identifying the EU exclusively with the market dimension and disregarding its potential role in the pre-market and post-market field would accentuate the distance with citizens and open the way for the populist attack.

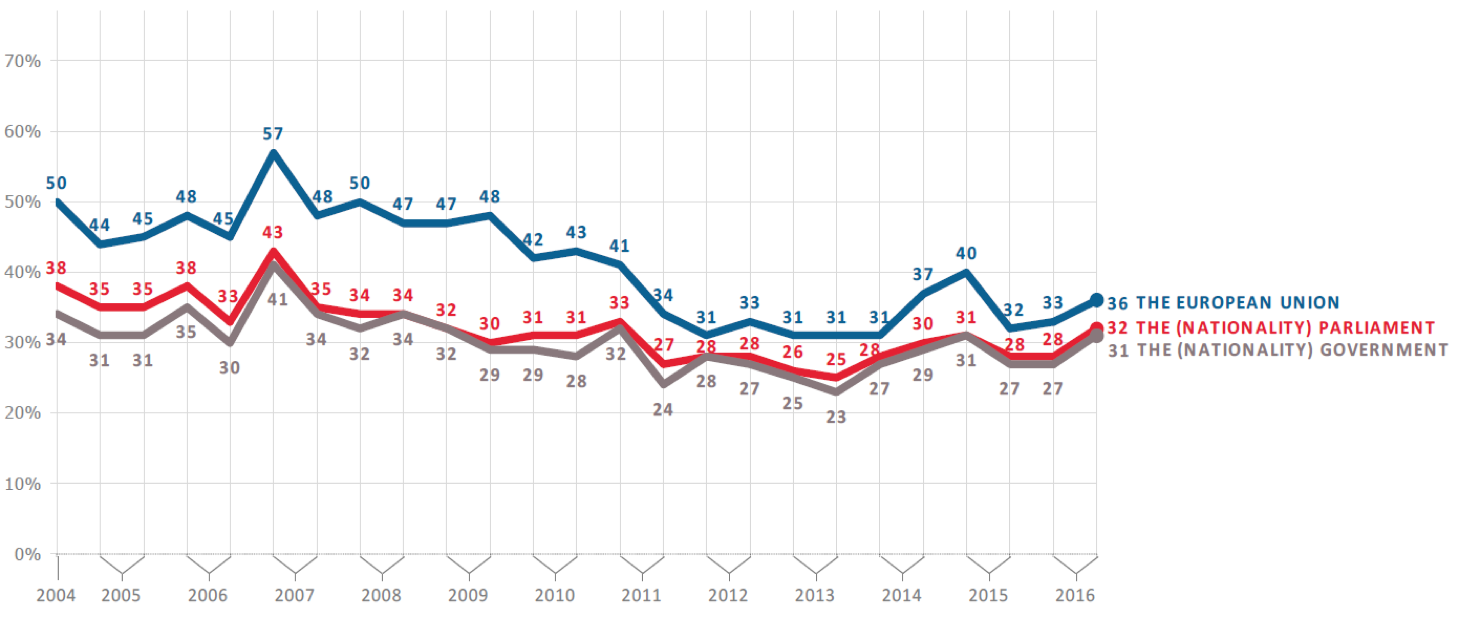

Similarly, a number of elements fuel anti-EU sentiments from a nativist-identity perspective. Charges of ‘homogenisation’ undermining, or even erasing, national specifics and identity are commonly brought up by populists mainly on the right side of the political spectrum. At the same time, the transfer of national autonomy and decision rights to EU institutions and bodies evidently shifts democratic control further away from national electorates. This is associated with a significantly higher complexity of mediation and, thus, intransparency of decision-making at the EU level, thereby increasing the distance to the ordinary citizen. A rules-based and institutions-based system, instead of being perceived as a guarantee for equal treatment and protection of minorities, is seen as an additional layer between ruler and the people. The inevitable loss of input-legitimacy[iv] from a national perspective can easily be transformed into allegations of eroding the sovereignty of the member state and the will of its citizens, eventually leading to the populist call ‘to take back control’. Moreover, the often highly technical issues to be resolved at the central level make it easy to depict EU policies as designed by soulless technocrats detached from the life of ordinary people and accused of ‘fake’ policy-based, pre-determined evidence-making. It is of little consolidation in this context that trust in the EU has actually held up better than trust in national institutions.

Figure 2 Trust in the EU versus national institutions

Source: Eurobarometer December 2016

Output legitimacy has clearly suffered as well, given the hesitant and still incomplete reaction to the financial crisis and its fallout, or the difficult handling of the migration/refugee issue. Protection of minorities and upholding the rights of citizens such as free movement of people – a stronghold of EU policies – can without much difficulty be construed as running against the will of ‘the no longer silent majority’. Enhanced by national politicians’ tendency to blame ‘Brussels’ for some of their own failings and their reluctance to give the EU credit for its successes, we witness widespread frustration with the EU’s ability to tackle the poly-crises we are confronted with.

Conclusions: Some Guiding Principles for a New Positive EU Narrative

Unfortunately, there is no quick fix. A sustained period of growth and rising incomes would help. So, too, would proactive policies to cushion the impact of liberalisation on the losers. But the present politics of middle class discontent demands a broader response to restore the trust in the European project. As long as EU integration is seen as a project of the political elites and the rich, it will carry the seeds of its own destruction. The growing polarisation in our societies needs to be addressed by finding better ways to combine the benefits of open markets and integration with democratic inclusion, social protection and fairness. Rebalancing is even more complicated in the EU integration context, where the divide between winners and losers does not merely follow the traditional fault lines along the functional and the personal distribution of income and wealth, but often also carries strong nationalistic connotations of north-south and east-west conflict.

Today’s reality calls for a rethink of the requirements of the subsidiarity principle in the EU, aiming to ensure that decisions are taken as closely as possible to the citizen and correctly identifying and redefining the areas where action at EU level is justified and needed in light of the possibilities available at the national, regional, or local level.

Against that background, we set out five guiding principles for policy articulation at the EU level to foster political stability, social cohesion and integration.

1. Focus on delivering the common public goods in need of well-defined EU value added

This involves strengthening security both at Europe’s external borders and internally, including a shared migration, asylum, and refugee policy worthy of the name. Tackling the environmental challenge is another area where go-alone policies are obviously bound to fail. International cooperation will also be required to fend off protectionist tendencies, wherever they originate, and to defend European interests in the global economy. And obviously, economic security starts at home with safeguarding and extending the Single Market achievements, completing the Banking Union, and taking the necessary steps to ensure the sustainability of EMU.

2. Re-establish the core values of the European social model as a joint response to globalisation

The EU’s social acquis already provides a floor of social rights, protecting worker’s health and safety, equal treatment and job security. However, in response to remaining gaps, allegations of ‘social dumping’, and the many new demands in a rapidly changing world of work, a critical reflection is needed; and, consequently, work on establishing a European Pillar of Social Rights is under way.

3. Mainstream distributional considerations into EU policy designs

While acknowledging that social fairness is primarily a domestic challenge, in the EU’s monitoring and surveillance processes more focus needs to be given to distributional issues. Stronger emphasis on the quality of public finances also contributes to higher intergenerational fairness and more tangible and intangible investments. The EU has become a strong actor in common strives for fairer taxation systems, as evidenced, for example, by current efforts to tackle profit shifting, tax evasion and the erosion of tax bases, and the use of competition policy instruments to address tax benefits granted selectively to companies.

4. Embody the new requirements derived from the subsidiarity principle in the EU budget

The EU budget, albeit limited in size, is one of the main tools for the EU to achieve its objectives. Thus, it is vital to ensure ‘vertical consistency’ between European and national actions budgets (Buti and Nava 2003). The recent crises have put extra pressure on the EU budget; they have also pointed to areas where EU action and delivery of common public goods is the most pertinent (see principle (i)). A dedicated fiscal capacity for the Eurozone could not only add to the macroeconomic stability properties of EMU, it could at the same time serve distributional functions, be it in support of social investment or in the form of unemployment benefit funds.

5. Ensure transparency and democratic accountability over the course of decision-making

The EU’s activities today affect millions of European citizens’ lives. The decisions having an effect on them must be taken as openly as possible. Admittedly, this is easier said than done, and despite many efforts to increase transparency, the perception of EU decisions as being driven by lobbying activities and backroom deals is widespread. There are many ways to streamline decision-making processes, making them more easily comprehensible. It is also essential that responsibilities of ‘Brussels’ and the national legislators are clearly identified, so that accountability – ultimately, the decision of citizens to re-elect officials – can be exercised at the right levels.

Implementing these principles will not silence the populists, but it will hopefully take the wind out of their sails to some extent. Such an effort also requires that mainstream political parties across Europe do not give in to the populist version of ‘blaming Brussels’ for difficult decisions to be taken domestically. Embracing the European project for what it is, namely a democratic endeavour to preserve and strengthen values shared by all European traditions, is even more essential in a time when international cooperation seems to be fading away.

Editors’ note: This column is a shortened and slightly revised version of a Policy Brief, LUISS School of European Economy, January 30, 2017. The views expressed in this article are personal and should not be attributed to the European Commission or its services.

Endnotes

[1] Obviously, the EU budget and its associated net cross-country transfers also perform some redistribution function, but it is very limited and mainly geared at the regional, rather than the interpersonal level.

[2] The ‘elephant chart’ of income distribution has become a reference point for the debate on the global inequality (Milanovic 2016).

[3] In the 1990s, Bauman coined the term “liquid modernity” to describe a contemporary world in such flux that individuals are left rootless and bereft of any predictable frames of reference. In books including Liquid Times and Liquid Modernity, he explored the frailty of human connection in such times and the insecurity that a constantly changing world creates where traditional institutions no longer fill the wells of common understanding and experience.

[4] The term goes back to Fritz Scharpf (1999) who introduced the distinction between input legitimacy of governance, i.e. the responsiveness to citizen concerns as a result of participation by the people; and output legitimacy, i.e. the effectiveness of policy outcomes for people. Vivien Schmidt (2013) later added the concept of throughput legitimacy, i.e. the governance processes that happen in between input and output.

Please see original post for references

“Can Europe Be Saved BY Populism?”

There’s my unsolicited headline edit :)

uh, uh, it’s:

“can populism be saved from europe?”

“Can populism be saved from racism?”

“Can the elite be saved from the guillotine?”

Might be their larger overall concern.

I have been wondering where the French retired all of those guillotines. Maybe they stashed them in some long forgotten warehouse. Prolly a good thing they didn’t ship them all to Greece.

“Memphis…did I forget to mention Memphis?!”

Mitterand was the last chap to use them on a hundred odd Algerians. I guess they remain in that ex-colony.

Unless MLP wins, in which case we are in a new Europe, I now think the next French President has five years at most to twist the arms of the Germans, and whoever else needs persuading, that without radical reform France will elect a President committed to withdrawing from the EU.

I write this, not because I think things in France are really that bad. As a country,despite its share of problems, it still has a lot going for it. But the French are a miserable bunch (I am part French myself and admit to this trait ) and therefore inclined to think the grass is greener elsewhere. Eventually I fear this will cause serious problems.

either the EU pays the piper in 2017 or 2022. it may be naive–but if LePen wins in 2017, LePen still will need a broad coalition of support to govern.

if things get worse by 2022 (guaranteed if Macron or Fillon?), LePen will run the boards in 2022 and it will be a true electoral revolution.

interesting times.

I think this may be correct. If Fillon drops a Thatcherite revolution as he’s stated, LePen will crush it in 2022. No one likes Thatcherite reforms.

My guess is that if LePen wins, the Germans will realized they’ve got to come to the table with real concessions on how things work in the EU. The changes will have to be substantive. I don’t know enough to know what that compromise might look like, but if the Germans dig in their heels, the EU might break up. LePen doesn’t strike me as a bluffer, but I’ve got no idea.

Isn’t populism simply the form of democracy where a bunch of people don’t vote as their elites instruct them to?

No, when they don’t vote as Gutmenschen think they should — elites do not necessarily care, what with the fact that corporatocracy it the common denominator.

I see “Europe” and I read “elites.”

The rich are getting nervous.

me, too.

This bit is classic elite-speak policy wonkery:

Try telling the crowd at a big, rowdy political rally that their skill-biased technical progress has not been Pareto-optimal. You’ll be lucky to escape with your skin intact as they holler “eat the rich,” brandishing their pitchforks and cell phones.

“Figure 1 Working class and low-skilled people tend to see globalisation as a threat.”

^That chart is an amazing depiction “skin in the game” vs. “no skin in the game”.

Then what is “globalization”? it’s many separate things.

To ask someone how they perceive globalization is nonsensical. Then it is perceived as different things by different people.

Main big parts may be internationalization of manufactures supply chains, where of 1/3 in the late 90s was inside the growing mega companies.

That in turn was made possible with global unregulated bank & finance where some hundred companies control 80% of the global business world.

Then its “free” movement of people, that is the neoliberal dogma that the left has adopted. That is totally given up that third world and poor countries should be helped to reformed and do social revolution to better the living condition. Instead the “solution” is that they should come here and share the “wealth” of the masses in the richer parts of the world.

Another thought about Figure 1:

Long time in education (not the same as being skilled):

Masters degree and therefore supposedly capable of independent thought?

Or, several years of being rewarded for repeating what people in authority says is right while being punished for disagreeing when/if disagreeing with authority? A good way of shaping behaviour….

I have the impression that it is about the latter, producing people who’ll believe what their ‘betters’ are telling them. (Load them up with debt makes them even more controllable)

Would be nice to see my theory tested, who is more likely to believe people in authority? The longer in education the higher the likelihood of believing in what people in positions of authority says?

Jesper, what an academic education teaches, among other things, is

1) Critical thought: do the arguments make sense?

2) Evidentiary integrity: are the sources properly and honestly cited; and is each source used with respect for its own intentions and argumentation, or is it misquoted, selectively quoted, or otherwise abused?

3) The language of the scholarly field, each of which has its own jargon, or shorthand;

4) The people you need to know to get along;

5) How to survive a debate in front of intelligent people without looking like a fool or a bully;

6) How to treat intelligent people with whom you differ with appropriate deference and diplomacy.

What higher education does not do, either in the humanities or sciences, is teach obedience, subservience, or submission. This may be completely different now from what it was when I got my advanced degrees, however.

PhilM, I have to respectfully disagree. The one thing that 16 years of education has taught most students is “Do whatever it takes to get an A.” That along with getting those three letters of recommendation enforces a lot of subservience and obedience.

It has been this way since Plato’s Academy invented higher education. Aristotle had to leave and found his own school. Does anyone remember who beat him for leadership?

Even Plato had to bow to nepotism.

Plato…

don’t forget time discipline, under arbitrary deadlines.

https://youtu.be/_EP7N2VtFz0?t=3m25s

PhilM

Your list includes what education SHOULD teach. My experience with academia (to LLM and adjunct professor status), is that strict adherence to the current academic dogma is mandatory, and that even asking a question about political correctness or feminism is academic suicide. Regimentation is now the rule, and any independent or critical thought will get the thinker shame labelled and drummed out.

Baloney.

This post is amazing but I guess not surprising. They really do not get it, which should not surprise since they are not only EU bureaucrats but from “economic and financial affairs.” As I read the post, the EU has thus far done nothing wrong, is totally misunderstood, and could solve whatever (perception) problems it has with a) better PR and b) more power (increasing the EU budget and giving it “limited fiscal capacity,” which I am totally sure they would use to provide EU-wide job guarantees. Not.). Oh yeah, and “transparency and democratic accountability.” Good one.

It should be noted that they seem to define “populism” as only its rightwing variant. I guess that is a sign of how weak the left in Europe is.

The deeply internalized neoliberal dogma is clearly seen in the EU Commission statementes, for instance, from the winter report for Spain:

But wait, this has to be done in “social fairness” and ensuring “inclusive growth”. This must be the new narrative.

These are few examples of such “inclusive structural reforms”:

1) Increase VAT until there is no deficit.

2) Further Increase VAT and spend it in R&D.

3) Enhance tax procurement

4) Wage moderation “creates” lots of jobs

5) Improve education (yeah, it must be education what fails)

etc.

They wont ever change this “virtuous triangle”, so try with the narrative. Include from time to time “inclusive”, “socially fair” and the magic will be done.

One amendment:

VAT was a French invention [it figures], introduced in 1954. No prize for guessing which direction VAT rates have gone since introduction — UP.

EU members are now required to impose at least a 15% VAT. Rates range as high as 27% in Hungary. The only European [and non-EU member] state with a single-digit VAT is Switzerland, at 8 percent.

A similar sorry history of ever-higher sales taxes applies in the US. From their introduction at low single digit rates, sales taxes have crept upward to the double-digit threshold in some localities.

All this might be okay if higher rates of tax had been used to fully fund social benefit schemes. But they haven’t. Escalating taxes actually have gone hand-in-hand with deterioration in the funding of social benefits. Heads should roll!

Amendment accepted

I really don’t know much about Japan but I have to point out that a lot of articles about Japan are far frow encouraging (crushing working hours, crapification of labour and less and less socialization for younger generations, culture of shame that leads to suicide or disappearance at the first sign of failure, calcified politics…).

I agree that to talk about the neverending Japan’s depression is misleading but when population is falling rapidly, I don’t think your society is doing very well…

>but when population is falling rapidly, I don’t think your society is doing very well…

I dunno about that as a measure, especially on something that is so obviously a freaking island – pretty obvious there are limits to growth and maybe there are already too many? But regardless, yes there are certainly serious problems in Japan. Yet I would say that they are way worse in Middle America – you’ve heard about the white people’s falling life expectancies? – but it’s averaged out with the thriving coasts.

So we Americans get to point at “Japan” and scoff just because geography allows us to blur our failings.

People reproduce at below replacement rates in advanced economies. This is also true for German natives. Children are part of the family labor pool in developing economies while are a drain on household resources in advanced economies. People either figure they can’t afford to have kids or don’t want to have kids (some women who stay single, DINK couples) and the people who do have fewer than in developing economies.

What masks that in other advanced economies is that they are tolerant of or even seek immigrants, who tend to come from countries with higher reproductive rates. The US was projected to show a population decline in the 2000 census. Demographers were shocked when it didn’t happen. Hispanic immigration and higher birth rates among Hispanics was the reason.

By contrast, Japan is famously unreceptive to outsiders.

The most racist people on the face of the earth. They proved it in the ’30s and have not changed one iota to this day. One reason why Japan is a giant geriatric ward.

The “stagnant” Japan is in aggregated per capita numbers not so bad compared to many others.

Here is a link to google public data World Bank statistics.

e.g. GNI per Capita, constant USD for Japan, France, Canada, UK and US.

A simple click and one could change to GDP, PPP whatever.

Japans unemployment figures have done better than US I think and much better than EU since 1990. Japan have record high NIIP (Net International Investment Position), 80-90% of GDP, Germany about 40%.

Japan population is 127 million and expected to decline to 80 million to >=2050. No country/area can have forever growing population. It’s happen before that areas have declined in population when they had become to many for sustainable survival. Malthus was wrong but that doesn’t proof that forever growing population is sustainable.

Japan have 1,523 persons per square kilometer for habitable land. More than 50% of population lives on 2% of land. (1993)

Will those Japanese islands be better or worse place to live on with “only” 80 million?

Is this healthy? I mean, having highest net international investment positions relative to GDP. Or is it the result of imbalances such as insufficient internal demand? Isn’t this the result of neoliberal policies focusing on competitivity?

Please see my comment above.

And you miss that it isn’t “neoliberalism”. Japan is vastly more egalitarian than any other advanced economy and recognizes the importance of preserving employment as key to social stability. That is firmly anti-neoliberal.

Japan also had a much more severe debt bubble relative in the late 1980s relative to the US in 2008 and a correspondingly worse post crisis hangover. It didn’t clean up its banks, which like ours were politically connected and told the US after its crisis that that was its big mistake.

No, it’s cultural. Being a wife in Japan sucks more than in other countries. Japanese men stay out late with their buddies drinking and are hardly home. So the wife is stuck with child-rearing and no help.

So more and more women have become what the Japanese call “parasite singles”. They live with their parents, have a job, and a nice lifestyle.

And to the other point raised, have you ever seen Japanese housing??? I visited an apartment that sold for $5 million in Tokyo at the peak of the bubble. It was at most 900 square feet and probably more like 800. A small galley kitchen, a not very large combined living-dining room, with three tatami mat sized bedrooms. Cramped housing is a disincentive to having children too.

On the subject of female life in Japan, there’s a girl who does a flourishing biz in and around Tokyo by providing wedding dresses to spinsters so they can get some nice photographs on the wall and give their friends something to wonder about.

In Japan a women can hire a boyfriend to show to the parents, presumably to shut down the nagging about never getting married for a while. Probably … or maybe this will allow the parents to let themselves be fooled into believing that their daughter has a boyfriend so that everything is totally normal even while knowing that she doesn’t want one. There is a lot of double-think in Japan..

If a woman gets divorced, she will have to leave the house and children to the husband. This often results in married couples having different rooms in the house, mistresses and affairs, which are only a “scandal” if they are found out – because being found out means that obviously one is not managing ones affairs properly, which is worse the higher the status of the person getting nailed. Nobody cares about the infidelity.

They also have “Geisha-boys”, for the women who have money to spend but doesn’t want to be seen going out or drinking alone.

Well to be honest I don’t know the composition of that statistics. But I could guess it have something to do with Japan being relatively closed and they not embraced neoliberalism, that any foreign interest can come and buy whatever they want. Japanese company’s is maybe predominantly Japanese owned and they don’t embrace foreign investments. While Japan is a successful industry nation and Japanese companies have a presence around the globe.

Probably not necessary that it’s a sacrifice the people. They at least don’t have EU/Germanys nutty neoliberal ideas on balanced budgets and public debt to get the domestic economy going.

There is a baseline assumption that populism is bad. That is what has been conveyed to me as blow joe.

Okay there was Hitler, if the outlet for populism is misdirected it is bad I guess.

But I think this is just the elite’s line that populism is bad to try to contain it, but when it overwhelms them they don’t contribute to functional solutions because it impacts their wealth negatively, they just up with the populism smear campaign and say “see I told you so” when it all goes south for lack of helpful from them.

Populism is code in Europe for Putin. At one point, it may have meant economic justice, but that is no longer the case. Today it means the far right, supported by Putin, is engineering a takeover of the entire European system.

A similar Putin scenario is being propagated here, but the word populism is still too closely associated with leftist activities to gain favor in describing the far-right.

When people want borders, home rule, and protectionism, they’re no longer considered members of Europe’s democratic endeavor. Breaking Europe apart will make it a sitting duck to be gobbled up by Putin and his right-wing cohorts.

So the article should really be titled “Can Europe Be Saved From Putin?”

Please Google Putin, Populism and Europe and you’ll have plenty to read.

No words. Just no words “AHHHHHH PUTIN IS TAKING OVER EUROPE AHHHHHHH”

The EU is not failing because ebil Putin wills it to fail.

No, it’s not. Timo Soini, a populist leader in Finland, has been pretty hostile to Russia. Fillon has good relations with Russia and Putin, and Putin liked Corbyn. Russia likes those who want friendly relations.

Russia is no threat. It could not Baltics without a huge trouble. Two mmillion Chechens, who had little foreign supprt were an enormous problem for Russia, and Russia probably would not survive a fight with even Finland. The costs of the war and the occupation would destroy Russia.

Putin, Russians reading western media are like the Jew reading Der Sturmer:

In 1964 I rode my Vespa motorscooter across India. I saw starving people. And some Indians riding Vespas. Naturally, I wondered, “Would those people be starving if the others did not have Vespas?”

Of course, populism is terribly bad, the elites has always known that. Populism means that the wealth and resources of the land should be used for the public good to benefit all citizens. We can’t have that, can we? It could hurt the elites and in practice transfer power to the many. As in the few little more economic democratic post war decades, also known around the industrialized world as boom and record decades for all. Low or almost non unemployment transferred power to the masses, we can’t have that, can we? That was the real reason the post war model had to be ditched. The masses became unruly.

As the history of the roman empire, all outburst of miss content by the people is described as very negative populism, the rabble was out and disturbed peace and order. Who historically has been that did write history? The elite.

Is this Populism a new thing in Europe? The Nazi era wasn’t really what I’d call ‘populism’, rather it was fascism from start to finish. You could even say it was a reaction to the uprisings which began in the mid 1800s. So today’s populism is a revival of genuine populist sentiment once again. The EU should embrace it whole heartedly because it’s prolly the only thing that can save any semblance of a ‘union’. At least they’ve got fresh ideas that can still bring people together. They don’t look like a bunch of blood-thirsty skinheads. But they are clearly frustrated with being asked to share sovereignty without a share. I don’t see how articles like this could possibly help the situation.

It’s populism when you don’t like the other guy’s politics.

It’s democracy when you do.

+1

A NYT Op Ed last earlier this week called on the just and the good (i.e. our neoliberal overlords) to “save” the upcoming French election from “the Kremlin’s grip” (paraphrased).

Are they going to wheel out the Russian specter every time the people “threaten” to elect a “wrong” candidate or party? This is ludicrous but nothing is really surprising anymore. Democracy has become a Russian plot…how insane is that. And how long are people with sound minds going to buy this hokum?

The signs are this version of capitalism has failed and not acknowledging it is causing a lot of problems.

The people expect elites to deliver the goods for the majority. This is their job and if they don’t do it they will be replaced.

The populist want leaders that can do their job, the same throughout the West. Elites today have an over-blown sense of entitlement, that had them serving lobbyists rather than their electorate. It’s all coming home to roost now.

Keynesian capitalism had ended in the stagflation of the 1970s and new market led capitalism came online to get things going again. Capitalism had reached another dead end in the Great Depression of the 1930s, this isn’t a new phenomenon.

Looking back with two assumptions:

1) Money at the top is mainly investment capital as those at the top can already meet every need, want or whim. It is supply side capital.

2) Money at bottom is mainly consumption capital and it will be spent on goods and services. It is demand side capital.

Pre-1930s – Supply side economics leading to:

Too much investment capital leading to rampant speculation and a Wall Street crash

Too little consumption capital and demand is maintained with debt.

Leads to the Great Depression and the debt deflation of an economy mired in debt

Post-1930s – Demand side economics:

Too little investment capital compared to demand, supply constrained.

Too much consumption capital, leading to very high inflation.

Imbalance causes stagflation.

Post-1980s – Supply side economics leads to:

Too much investment capital leading to rampant speculation and a Wall Street crash, asset bubbles all over the place.

Too little consumption capital and demand is maintained with debt. Global aggregate demand is suffering and with such subdued demand there are few places for real investment leading to more speculation.

Leads to the secular stagnation of the new normal, the assert bubbles have yet to burst.

Each version of capitalism does what is necessary to get things going again, but after it has been running for several decades it has shifted the balance too far in the other direction and ends up in stagnation.

We need to keep the supply/demand balance as close to its optimum as possible at all times.

It is a balance between investment capital at the top and consumption capital at the bottom.

Debt based consumption is only ever a short term solution and cannot be used over the longer term. Greece used debt based consumption until it reached max. debt and then it collapsed.

Today it has been used to keep the supply side model running much longer than should have been the case and it will end badly.

The Central Bankers have spent eight years trying to encourage further debt based consumption with QE and ultra low interest rates but the inflation rates within the developed world stay way below the 2% target. The consumers have maxed. out on debt already and they can’t take on any more.

The Central Banker’s monetary policy tools have stopped working.

The same thing happened in the Great Depression and it needed the fiscal stimulus of the New Deal to begin to resuscitate the debt saturated economy.

To me it sounds like:

populism = democratic accountability

globalism, trade, integration, EU, TTIP, TTP = unaccountable structures designed to run circles around accountable structures like nation states and elected parliaments.

The second bunch of structures is trying to strangle the first bunch, including in the propaganda war. After all, the last 45 years or so, since the 1970s, have proven that indeed the pen is mightier than the sword.

There shall be reckoning in the streets at some point, but I am not holding my breath. Nations have endured 4-5 years of wartime destitution and wholesale killing before deciding its enough, and 40-50 years of communist dictatorship extraction, labour camps and shortages before rebelling. By roughly extrapolating those time periods, we should have 60-70 years of neoliberalism… Elites do feel comfy!

When push comes to shove as it did with the migrant crisis, the European Union’s narrative/policies have been shown for what they are – huff and puff. Its function now appears to be glorified standards agency with adjuncts of creating employment for overblown mission statement writers and sub-par politicians. The real-politik which is on display at every moment, is that when crisis comes knocking at the door, no-one looks to Brussels for a power-play. Power rests with the those who are regarded by the masses as the leaders of the sovereign states. It is with the Merkels and Berlusconis that their fates lie. Granted, EU membership may modulate the individual leader’s actions, but (if democracy is what Europe has) populism, or the gaming of populism “at home” is always going to be at the forefront. In the legitimacy stakes the EU is just the race-track management.

– a disappointed Brit.

EU, a colossus on clay feet. Recently Italy asked Russia for help with their dire migrant crisis.

EU mandate this and that and Greece is put on austerity on steroids and get no real help and solidarity on their migrant crisis.

When Yugoslavia started to crack, EU had an united policy that lasted five minutes.

Elites talk down to the working class at their own peril. Austerity and mass immigration is a recipe for catastrophe.

Collapse is the final stage of change…

The populists are rising due to the failure of today’s economics to deliver the goods for the majority.

The Euro was designed with today’s economics, which isn’t very good and means the Euro doesn’t work just adding to the problems.

Today’s economics has been corrupted.

There are two approaches to economics top-down and bottom-up.

Observing the real world and drawing direct observations doesn’t allow for the corruption of economics, cunningly crafted low level assumptions allows bottom-up economics to be corrupted.

Classical Economics is of the top-down variety where they made direct observations of the real world, which was a world of small state, basic capitalism. Today’s expectations of small state, basic capitalism are rather different to those observed when it actually existed before.

Adam Smith observed early small state, basic capitalism in the 18th century:

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money.”

We still have an aristocracy that is maintained in luxury and leisure and can see associates of the Royal Family that are maintained in luxury and leisure by trust funds. As these people are doing nothing productive, nothing can be trickling down, the system is trickling up to maintain them.

Today’s bottom-up economics allows us to think the system trickles down, it has been corrupted.

The Classical Economists direct observations come to some very unpleasant conclusions for the ruling class; they are parasites on the economic system using their land and capital to collect rent and interest to maintain themselves in luxury and ease (Adam Smith above).

What can these vested interests do to maintain their life of privilege that stretches back millennia?

Promote a bottom-up economics that has carefully crafted assumptions that hide their parasitic nature. It’s called neoclassical economics and it’s what we use today.

The distinction between “earned” and “unearned” income disappears and the once separate areas of “capital” and “land” are conflated. The landowners, landlords and usurers are now just productive members of society and not parasites riding on the back of other people’s hard work.

Unearned income is so easy, it’s the UK favourite today.

Most of the UK now dreams of giving up work and living off the “unearned” income from a BTL portfolio, extracting the “earned” income of generation rent.

The UK dream is to be like the idle rich, rentier, living off “unearned” income and doing nothing productive.

Also, the assumptions on money and debt do not reflect the true nature of money and debt leading to further problems like 2008.

Look at the real world; it’s much better than today’s economics.

Looking at the real world, I worked out what happened in 2008.

Money was obviously destroyed in 2008, but today’s economics has no mechanisms for the destruction of money.

It uses flawed assumptions on money and debt that it works up into models that don’t allow you to see things like 2008 coming.

2008 was easy to see, it’s just Central Bankers are trained in neoclassical economics and these economists couldn’t see what was coming.

This is the build up to 2008 that can be seen in the money supply (money = debt):

http://www.whichwayhome.com/skin/frontend/default/wwgcomcatalogarticles/images/articles/whichwayhomes/US-money-supply.jpg

Everything is reflected in the money supply.

The money supply is flat in the recession of the early 1990s.

Then it really starts to take off as the dot.com boom gets going which rapidly morphs into the US housing boom, courtesy of Alan Greenspan’s loose monetary policy.

When M3 gets closer to the vertical, the black swan is coming and you have an out of control credit bubble on your hands (money = debt).

The theory, which is outside the Central Banker’s neoclassical economics.

Irving Fisher produced the theory of debt deflation in the 1930s.

Hyman Minsky carried on with his work and came up with the “Financial instability Hypothesis” in 1974.

Steve Keen carried on with their work and spotted 2008 coming in 2005.

You can see what Steve Keen saw in the graph above, its impossible to miss when you know what you are looking for.

It’s all about how money and debt really work and the creation and destruction of money on bank balance sheets.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

Money is created from loans and destroyed by the repayment of those loans.

Money = debt.